Powered by RedCircle

Listen at: Spotify | Apple Podcast | YouTube | Stitcher | RadioPublic

Welcome to Episode 10!

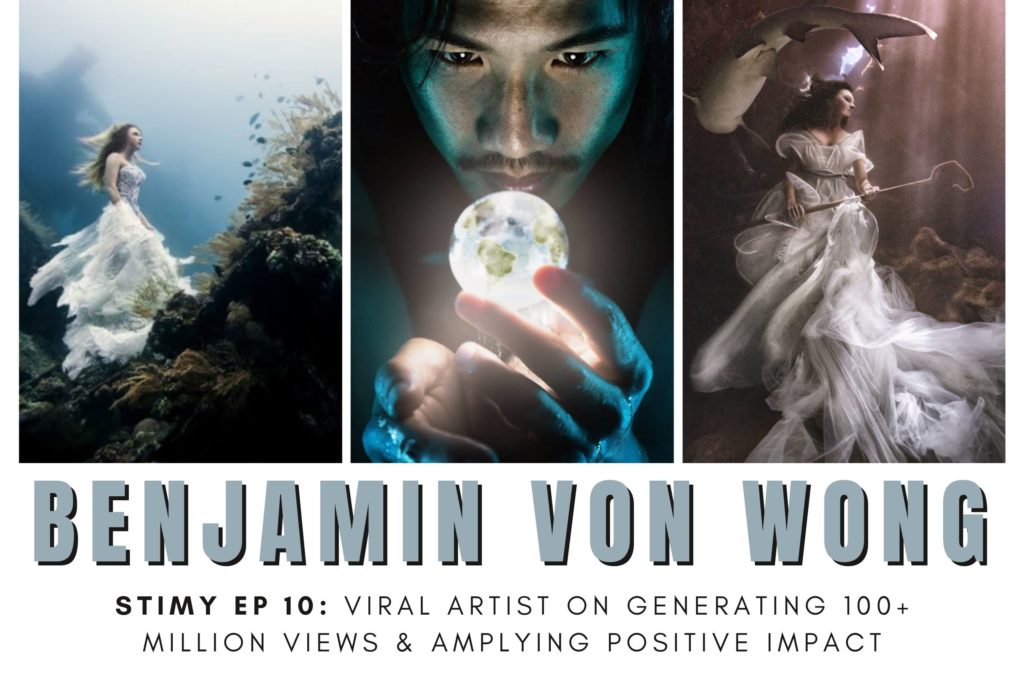

Our guest for STIMY Episode 10 is Benjamin Von Wong.

Benjamin Von Wong is Canadian mining engineer turned artist/photographer who designs campaigns around social impact and has succeeded in raising over 100 million views for different causes including plastics, fast fashion and electronic waste. He has a Guinness Book Record, a community of over 500,000 followers and tries to change the world through amplifying positive impact.

Who is Benjamin Von Wong?

Von was born in Canada and his parents are first-generation Chinese Malaysian immigrants. With something of a “chaotic” childhood – he went to 13 different schools in 3 different countries – there was nothing in his background that suggested that he would end up with an artistic career.

Instead, he became a mining engineer in Nevada.

Until one day, driven by a breakup, he purchased his first $100 camera from Walmart. A purchase that set him down the crazy, artistic trajectory he is currently on.

Becoming a Photographer

The transition into being a full-time creative wasn’t immediate, and some of the things we discussed included:

- Why quitting his engineering job was less a question of courage, and more out of “fear”

- Why photography ended up being the thing that drew him in for the long term;

- How he first got his start in the industry, and the most popular platforms to use at the time;

- How he ran a Kickstarter to fund his Von Wong Does Europe Tour;

- Some of his projects including the 365-day project; and

- Von’s 3 most impactful work prior to entering the social impact space.

Within 3 years, Von attained the highly sought after global campaign with Huawei where he had to create an angel with fire wings.

Entering the Social Impact Space

After the Huawei campaign, he felt empty. And this signified another pivotal point in his life, only this time it was into the social impact space:

- Why was it so hard to enter the social impact space?

- Why was the mermaid with 10,000 plastic bottles project so successful?

- How does he measure the impact of art?

- Does he worry about alienating potential clients after entering the social impact space?

- What is his metric of success?

If you’re looking for more inspirational stories on STIMY, check out:

- Red Hong Yi: Malaysian architect turned artist who paints without a paintbrush. Works have been commissioned by the likes of Jackie Chan, Google, Facebook and Nespresso. Her artwork was recently featured on the TIME Magazine’s 26 April 2021 special issue on climate change

- Tan Kheng Hua: Hollywood actress most known for her roles as Margaret Phua (Phua Chu Kang) & Kerry Chu (Crazy Rich Asians)

- Nick Bernstein, Part 1 & Part 2: Senior VP, Late Night Programming (West Coast), CBS & executive in charge of the Late Late Show with James Corden

- Morgan Then: Electronic music artist & Sarawakian half of Slumberjack (which has received 2 ARIA Gold Records)

- Sarah Chen – Co-Founder of Beyond the Billion: a global consortium of over 80 VCs that have collectively pledged over $1 billion in funding in female-founded companies

If you enjoyed this episode, you can:

Leave a Review

If you enjoy listening to the podcast, we’d love for you to leave a review on iTunes / Apple Podcasts. The link works even if you aren’t on an iPhone. 😉

Send an Audio Message

I’d love to include more listener comments & thoughts into future STIMY episodes! If you have any thoughts to share, a person you’d like me to invite, or a question you’d like answered, send an audio file / voice note to [email protected]

External Links

Some of the things we talked about in this STIMY Episode can be found below:

- Von Wong: Blog, Unforgettable Labs, YouTube, Instagram, Facebook, Impact Everywhere Podcast

- Some of Von’s works: Bali shipwreck, Shark Shepherd 50m underwater, Mermaid with 10,000 plastic bottles, #SavingEliza

- To participate in Von’s latest project: The Other Heroes Project

- Von’s mum on Instagram: Vonmum

- Subscribe to the STIMY Podcast for alerts on future episodes at Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Stitcher & RadioPublic

- Leave a review on what you thought of this episode HERE or the comment section of this post below.

PS:

If you want to get an alert about upcoming episodes & be the first to know about freshly booked guests, subscribe to the newsletter below!

I’m constantly sending out information about guests & also asking for questions from my subscribers.

You don’t want to miss out!!

Ep 10: Benjamin Von Wong - Viral Social Artivist on How He Generated Over 100 Million Views

Von Wong: I think people want to touch the extraordinary. People want to be a part of something cool. That's unique and different. And once in a lifetime. People pay money to do that.

And if you can offer them the opportunity to do that without paying money

To be able to use who you are as the key ingredient to make something impossible possible, and to be able to touch upon that, I think is a really powerful feeling. And so when I ask for help with volunteers, I try to really make it about the experience of doing something that they could have never done otherwise.

And to be a part of something greater, to be a part of something really big to be a part of like a movement.

Ling Yah: Hey everyone. Welcome to episode 10 of the So This Is My Why podcast.

I'm your host and producer, Ling Yah, and today's guest is Benjamin Von Wong.

Von was a mining engineer in Nevada but following a breakup, he purchased his first $100 camera from Walmart and kickstarted his entire journey into the creative world.

To date, Von has generated over 100 million organic views with this work ranging from photographing free divers tied to a shipwreck off the coast of Bali to creating a fire painting of a girl with angel wings as part of a Huawei global campaign. His photos are epic. Larger than life. On the scale that we do not often see. Pushing the boundaries of what is possible.

We covered a lot of ground in this episode, including how Von first established himself in the creative world, how he brought some of his most famous fire projects to life, the various elements required to create viral content and also the question of impact. Of why he decided to enter the social impact space, how he is amplifying positive impact through his work, the metrics of success that he uses as well as what his plans are as a result of COVID-19.

Let me know what you've learned and what's helped you in this episode by going to Apple Podcasts to leave a review and subscribe.

And also take a screenshot of today's episode on Instagram and tag me at @sothisismywhy and Von Wong at @VonWong with the hashtag sothisismywhy.

If you want to hang out, we also have a private Facebook group to keep the conversation going. And a number of our podcast guests are also there.

To join, just head over to Facebook and look for So This Is My Why, but for now let's jump straight into today's episode with Benjamin Von Wong.

Are you ready? Let's go.

Hi Von, thank you so much for joining us today .

Von Wong: Thanks for having me

Ling Yah: So you have had such an interesting career from being a mining engineer to being someone who's known for his photography and I just wanted it to really delve back into your start by just asking the question of what was your childhood like, and if there was anything in it that pushed you to us this whole space.

Von Wong: My childhood was very chaotic. I went to 13 different schools in three different countries in three different languages.

My parents are first generation Chinese Malaysian immigrants, and I was born in Canada. I don't know if they were actually below the poverty line, but they were definitely not much higher than that.

That being said, I feel like I didn't grow up in poverty in that my parents never struggled. We always had food on the table. If we needed to do an extracurricular activity, they would find a way and they just collected coupons and they were very frugal with their money in order to make that happen. And so growing up, I had violin lessons. I had drawing lessons. I had martial arts lessons. I had dance lessons.

So we just were always like learning something.

One would assume that I had an illustrious artistic career, but I sucked at everything.

So despite my parents trying to give us all the opportunities so that we could study all these different things, I just was never really great at any of it.

When I was at school, I was good at math and physics.

What else do you do? Um, just go into engineering. And it just so happened that hardrock mining engineering was the engineering field that was going to pay them off. That was going to have the most travel opportunities and that was close to home. And so it just ticked all these boxes and seemed like the right thing to do.

That being said, I think maybe one formative experience within my childhood between a high school and university was the first job that I got as a camp counselor. And so this is I think the first time where I was surrounded by people where the weirder you wore, the cooler you were.

Basically kids just love you if you're weird and funky and authentic. And I think that gave me permission to be weird. Whereas prior in my life experiences, as I was traveling around, there's always a sense of being the new kid and trying to fit in. And I just never quite felt like I fit in anywhere.

And I think it was after that experience that it became okay to be weird and different and to just do your thing. Which is something that I think I really carried on all the way until today.

Ling Yah: So you were in Nevada and then unfortunately had this breakup with your girlfriend. Can you tell us how that ended up pushing you into this whole world that you're in right now?

Von Wong: I was working in Nevada as an intern. I was dating a girl at the time.

It was a long distance but we had only kissed once or twice, and then I was gone. So it was just one of those romantic flings that really shouldn't have been a big deal, but it was. And so, because I was in a new place, I was not even 21, so I couldn't drink.

You have no friends and you don't really have a car or you have nothing to do. Do you have nowhere to go? I mean, a 10,000 person town in the middle of the desert with nobody.

I mean, teenagers hang out in the Walmart. Like that was the only thing to do. And so I find myself really trying to find something to keep myself busy with. And after this breakup, I just needed something to keep myself busy. The stars were beautiful. And I just decided that maybe I could try going out and taking pictures of the stars.

So I went to Walmart. I bought the most expensive camera that was there and realized that it couldn't do what I wanted it to do. So I returned it. I bought a cheap camera. It didn't do what I wanted to do. I bought the most expensive camera. It still didn't do what I wanted it to do. And I returned that one.

And then I ended up borrowing a car, driving to the next city over to buy another camera. I just walked into the store and said, yeah, I want to take pictures of the stars, what can I buy for like less than a thousand dollars? And this guy recommended the thing and I bought it and I just sat down at a Starbucks reading the manual and trying to figure this out.

And so that's kind of how I got started.

It was a hobby, but it kind of evolved into a companion. It evolved into something that I could bring with me anywhere regardless of where I happen to be, if I felt like the new kid at a party, I could still have a camera and use that as a conversation starter.

And so this thing sort of became not only a friend, but a way to make actual friends. It gave me a community to kind of attach myself to.

When I went back to Montreal, I joined a photography club and this just became something that I could do. And over time it became increasingly clear that photography was sort of like an access pass.

It gave me access to places. I would never be invited to places that I could never go to. I could go behind the scenes and different things.

And I think that's really what drew me to it initially.

Ling Yah: And I think you ended up going to music scenes and also sporting scenes and just covering a meeting of these interesting people.

So one of your biggest moments was being asked to photograph for pharmaceutical students, wasn't it?

Could you tell us how that opportunity arose?

Von Wong: Yeah. Yeah. I was in a photography club at the time.

And this professional photographer just couldn't make the event.

And so he asked if I would be interested in covering the event for him. It paid $250 and unlimited amounts of alcohol. And the job description was like six hours taking pictures of kids graduating or whatever. And I was like, oh, cool. That sounds like so much fun. And I went there and I had a blast and it was, I can get paid to have fun.

This is something that's so weird because it was all about paying to have a good time, not getting paid, to have a good time. And I think that's when I gave myself permission to start really going deep, because if I could earn money, then I could start spending more money. And so I started buying more gear.

I started buying more cameras and all the money that I started earning. I started refunneling back in and that gave me more money to buy more toys. And it just became this fun self-generating thing. While on the side, I just did my engineering stuff. And so evenings and weekends were completely taken up by shooting events, musical events, portrait sessions of different people.

Whatever I could lay my hands on. It was wonderful.

Ling Yah: And did your family, for instance, start to notice this change and ask you, what are you doing with yourself and why is this sudden shift?

Von Wong: I don't really think so. I mean, I've always been very obsessive over things, so I'll get into something and I'll go really, really hard at it.

Like in my teenage years, I got into gaming and I would play eight hours, computer games a day. And I was on these forums. I was trading. And at the end, I ended up like selling my characters for thousands of dollars.

Later on when I went to university, I picked up paintball and I was buying all these like paintball guns and playing, and it's just kind of what I did.

And invariably, every hobby that I kind of picked up would last about a year, a year and a half. So my parents were just like, oh Ben's on to his next crazy thing. I hope this one doesn't last too long, whatever, stop spending so much money.

And it just happens to be the one thing that I could never shake off.

And I think it's because of not only the fact that it was able to make money, but also is able to build community. So then my friendships started to build around that and coalesce around it. And the feedback loop of photography is very, very rapid.

You can see what you're doing badly really quickly.

And so the combination of those factors, I think, is what made photography kind of stick.

Ling Yah: And what was the industry like then? Were people very supportive and what kind of work did people tend to do?

Von Wong: I think it's like photography's glory days. Honestly, it was right at the time where big names like David Hobie, Chase Jarvis, Zack Areas. They all just started sharing the behind the scenes on how they were doing things.

It was all these guys that had tons of experience in the field. And were blogging about how to do their lighting, setups, how to set things up, tips and tricks. Whereas I think five years before that photography was a black box, you didn't share what was going on. And I think it has a combination of things to do with the advent of digital, the advent of social media, like all these things, were blooming and blossoming and growing at the time.

And so when I started, it was right around the time where F stoppers had gotten formed. And F stopper is at the time when I discovered them, we're only posting one video a day. One behind the scene video day. And if you were lucky enough to get on that behind the scene video featurette, this whole community would see you and it was a thriving community.

So that's when I started getting into behind the scene videos, because I realized that by simply showing people how you were doing things that exact same photograph could now get a lot more traction because you were revealing something about it, just like a magician revealing a magic trick.

And so this idea of sharing the process and giving back to the community and then getting inspired by the community was this very positive social structure that gave me a lot of, I think pleasure and joy, and I think that's maybe the most important part of it, right? Like it's not supposed to feel like a slog. It's supposed to feel fun and encouraging and inspirational.

And so the feedback loop of one cycle would feed the other. And I think at the time, so long as you were like putting out a video once a week, that was considered the standard.

Whereas now today, I think it's like, Oh yeah, put out like three videos a day. It's just becoming really too much in my opinion.

Ling Yah: So you mentioned how they were posting behind the scenes. So I assumed you were talking about Facebook because Facebook was really big at the time and you were also on Flicker.

So is that what motivated you to get on it? Because you're really successful. I mean, like you have so many fans that call themselves vonwonglings as well. So can you tell us what it was like in those early days for you.

Von Wong: Yeah. I don't know if fans equals success, but you're right. Facebook and flickr were pretty big at the time.

Flicker was where you'd find the dedicated photography community who were really interested in the technical aspects of photography. But Facebook just seemed like the place where you would reach more people.

All the people who weren't on flicker were on Facebook. And so at the time there were no algorithms.

It was all about if you posted people would see it. If more people commented on it, it would be shown to more people. It was a very simple algorithm. I basically built myself up to a following of about 7,000 followers by 2012. I think I had more engagement then than I do now. And now I have 350,000 followers on Facebook.

So being the right platform at the right time with the right strategies, I think plays a huge part into it. I think I got lucky with the Facebook wave. As with all waves, I have a sense that I've always sort of missed them. I kind of joined a little bit too late. I did the same thing with Instagram, really waited until the whole fad had petered out before I kind of hopped in and be like, I'm here.

But I've always gained just enough success to keep going. And it's funny because people really respect numbers, even though they don't necessarily mean that much. But the great thing about numbers is they never go down. Right. So my followers don't go down. My engagement goes down, but my followers don't go down.

And somehow people are impressed with my follower number.

Ling Yah: At the time you were also getting quite a lot of work. But then after two years, you felt that that wasn't for you. So what was your thinking process then? What did you think of doing?

Von Wong: As with everything that becomes successful, it sort of gets operationalized.

So with my event photography, it was going really well. I think I was charging a couple hundred dollars an hour and I just started getting a lot of requests because I was fast. I think I was reliable and I think the work was okay. And so the combination of doing things like fast, good and fairly affordable meant that I was getting work, but I still had a day job in the end.

At some point I remembered that the reason I started photography was because I wanted to have a good time doing it. Not because I needed a second career and photography was never meant to be a job replacement. It was only just meant to be a hobby. And so when I realized that I decided to shut down the event side of my business and just focused on doing weird creative things.

So I decided that instead of trying to do creative things that were really rapidly put together over the course of a day let's say, to really double down and go out and find models and build costumes and scout locations and do things that were a little bit more elaborate.

And I think that's why you see my work is a little bit crazier today is that in my earlier days, even then I was like, I really enjoy doing something that nobody else is doing. I will really want to go the extra mile and challenge myself to do something that I have never done before, because if you've already done it, why bother doing it again?

Ling Yah: And is this where your 365 project came about?

Von Wong: Yeah. The 365 project coincided driven by yet another breakup. Breakups are very significant in my life. I use them as I guess inflection points to transform my life. And in this case I was like, okay. A girl broke up with me. I need to find something to do.

I am going to double down on my creative stuff. I'm going to buy a bunch of gear. I'm gonna learn how to use it. And I'm going to launch a new creative endeavor, which was like a photo a day for 365 days, which was an excuse to kind of express myself.

The 365 day project was the impetus for me to realize that just doing creative things in a rapid iteration, wasn't enough that I wanted to invest more time into creating more complex things because that cycle of having to produce all the time means that you don't have enough time to put enough thought into the bigger stuff. And that it was always the stuff that I had put more time into that gave the better results. So if you're results focused, just turning things out all the time, isn't really the best strategy.

At least in my opinion. I mean, some people can do it for me. I find it really, really exhausting.

Ling Yah: So when you're talking about results at that time, were you focusing on making it viral?

Von Wong: Not particularly, I think I was focused on building community. So I was focused on entertaining my fans and followers.

I had a very educational focused photography career. And the idea was like, okay, everyone's sure how they've been doing things. I'm going to show them how I'm doing things. And I think it was really about trying to push the boundaries of what was possible. So if everyone was sharing a three light setup, what happens if I shared a three lights set up with birthday sparklers.

Or if everyone is sharing, how to shoot small sets with things on fire, like why not just let a person on fire? So it was always to take what's already being done and then add one level to it.

Ling Yah: And then clearly you liked it so much because in 2012 you decided to quit.

And what was that turning point? What gave you that courage, I think to just say, nevermind, I'm going for it.

Von Wong: Yeah, it's a funny thing, because most people think that quitting your job was like a super courageous decision. I think it was actually more like the opposite.

I just woke up one day and realized that I didn't want to be an engineer for the rest of my life. Like, I didn't want to be a photographer because I think in Asian culture, this idea of being an artist is never the glorious thing. Art was not supposed to be my calling.

And even though I didn't know what I wanted to do, I knew for sure that it wasn't supposed to be mining engineering and that if I didn't do anything about it in 10 years, I would be sitting at the same desk. Or maybe a bigger desk doing the same job, getting a slightly bigger paycheck. And it just felt so pointless.

And so I was terrified of that future. And so I actually quit less because of bravery, but more because of fear that I was just going to grow obsolete and old and boring. And so when I quit my job.

I negotiated with my parents or I didn't really negotiate. I just kind of announced it, but in order to placate them, I said, I was going to go and get an MBA.

So I studied, I got my GMAT. I got a decent score that would have gotten me into a university, whatever.

But because I quit my job in January because I hadn't thought things through, I had some time. So I figured, well, if I have time, I'm just going to go and travel. At which point I started to realize that the best way to travel for free is if you do photography, because I could teach a workshop somewhere, I get a free flight somewhere and I'd make friends and then I'd have a free place to stay and so on and so forth.

And so I just basically started traveling for free. And after the first six months it was going so well, it didn't seem like a good idea to stop. So I just kept going. Because the GMAT is good for five years. Right. And so it was like, there's plenty of time. I can always go back to school later, but what I have now, like all this momentum that's building, I started getting sponsorships because I went from being a local photographer to an international photographer and it didn't matter that I wasn't getting paid, but it sounded really impressive.

And so there's all this momentum behind what it was doing and it just didn't seem like a good idea to stop. and so it just never stopped. And I think my GMAT has now expired. So that ship also sailed.

Ling Yah: So that entire tour was basically the Von Wong Does Europe Tour. And you actually said in some of your lectures and just now as well that you wanted to travel, but you didn't want to pay for it. So you actually did a Kickstarter and that was actually really successful. So how did you go about doing that and also ensuring that you could supplement your lifestyle for such a long time?

Von Wong: The Kickstarter was an idea that just kind of came to me during one of my trips.

So the first thing that I did after getting my GMAT was travel, and it was actually in conjunction with another breakup. I think I was in the mind space of wanting to run away from Montreal. I was like, I don't want to be here anymore.

There are too many memories. It sucks. And so I went to Israel, which was the farthest place I could go for free using credit card points that I knew someone who had a sofa I could sleep on. So I ended up in Israel. I think that week there were bombs flying. There were missiles flying, like just a couple of kilometers away from the place I was staying.

I was like, oh, this sounds so exciting. Anyways, I go there, I hang out and I'm talking with this friend of mine who runs a blog. And I just start thinking about like, Oh, you know, it would be so cool to be able to travel the world and meet people that I've wanted to shoot for the longest time, because now I'm free.

But how do I do it? And I think it gave me the idea of starting a Kickstarter. So the Von Wong does Europe tour was born .

It was something that I had never done. I had never asked anyone for money. I had this YouTube channel, I had 7,000 followers on Facebook. I was, you know, I'd gotten featured on blogs, routinely.

The video that I had that had the most views, that had a hundred thousand views, which I think was a lot more than it currently is worth today. And so I had a little bit of wind behind my sails and I was like, what if I just tried doing a Kickstarter and offering a tutorial in exchange?

What if I just offered to document this entire journey of a person who just quit their job,

Trying to travel around and live their passion, right? That's a dream I think many people have this idea of quitting their nine to five. And so I just used my own life as a story to capitalize on the Kickstarter raised $12,500. And we sold a bunch of tutorials, which ended up being so, so, so hard to do.

I got my first sponsorship as a result of that. And it was a great experience. It was exhausting to go and try to create this, but even harder to produce the materials to market them afterwards, because even though our trip was paid for it. All the work, that behind the scene videos, all that was still volunteer.

And while it's a lot of fun to build, it's a lot harder to deliver because a lot of the momentum is taken out of your sales. So. I think if anyone wants to do a Kickstarter, go for it, but it's really, really hard. Just remember that it's really, really hard because at the end of the day, you're basically doing a presales camp and before you've done anything.

And so all the work actually happens like right after. And it's pretty tough.

So, after doing that Kickstarter, I wanted to keep traveling, but I didn't want to ask people for money anymore because I was like, this is too hard. And so the workshop thing of, wanting to go and teach people, started bearing fruit and I kind of used all the contacts that I had built through my first tour, all the different photo clubs and said, Hey, I'd like to come back.

Do you want to help me organize a workshop? And it'll be free for you and your friends. And I just needed to get enough so that I can continue to travel.

And so that's kind of how it worked.

Ling Yah: And I was wondering, how did you begin to even pick your project as well? Because you did everything from going to Paris to work with a pyrotechnician to working with the National Slovakian Ballet to working with the Superbowl leather mask designer. So they are so varied and over the place.

And you mentioned as well, that you were creating for the sake of creating rather than thinking of, Oh, who hired me after this. So what was that thinking process like?

Von Wong: Yeah so I'm an extrinsically inspired person. And I think even though my art is technically photography, when you break it down, my art is actually collaboration.

And so I spend an inordinate amount of time talking to people and just having conversations and learning about what they're doing and through that process of conversation and exploration, you learn about new places. You learn about new people. You learn about new things. And in my earlier days, it was a lot easier because all I needed was a cool person and a cool place.

And so I could just go and take a picture and I had all the camera, it was entirely self contained. So I could be the bridge between these worlds.

And so anytime I find someone interesting, who was doing something then cool, I just be like, all right, cool. Let's collaborate. I'll come to you and you just do your thing and I'll do the rest of it.

And if you know a place, then let's go to a place and so on and so forth. I think lately it's gotten a lot more complex because not only do I have a brand that has sort of been being built and grown then, so with that brand grows as expectations. But I've also got into the impact space. And when you do impact work, you can't just go and do impact.

It doesn't work that way. You're not creating for yourself, you're creating for someone else. And so you need to go, you need to take the time to talk to them and learn about their problems and figure out what the actual problem is so that you can offer a solution and not just be screaming out into the void.

And so I kind of miss those earlier days because it was truly a simpler time where I could build and create whatever it is I wanted to do whenever I wanted to do it.

Ling Yah: Yeah, but even in the simplest case, you were also already living an impact on people. I mean, you have people like Eliza, the little girl with the Sanfilippo syndrome, you had Tyler, grace, you had Nicole McKenzie who is terminally ill, just coming to you and just, you know, asking you to do something that will really impact their lives.

And what was it like just doing these projects that were pretty different, but quite similar to what you were already doing?

Von Wong: Yeah. You know, I love that you did your homework. There's three stories are probably like the three most impactful moments, in my photography career, because-

So for those who are listening, who don't know, Nicole McKenzie was diagnosed as terminally ill and wanted to have a photo shoot so that she could choose like the final portrait that was sitting on her when you die.

And for some reason she really, really wanted me to take those photos and I was like, Oh, okay, cool.

It just required me doing whatever I did. But the fact that I wasn't just creating to create a pretty picture. I was creating something that had a lot of meaning and purpose behind. It was super impactful.

Similarly with Eliza, her father reached out to me randomly by email and just said, Hey, I saw you know how to make things go viral. We're trying to make a viral video of my little girl who is dying of a terminal degenerative brain disease.

And we're trying to raise money to fund a clinical trial. Do you think you could help? And so I flew myself over, stayed on their sofa for 10 days. And ended up making a video that raised over a million dollars in a month, $2 million over the course of a year. And that was after saying, I haven't really done videos before, but if no one else is going to help you out, I'll be happy to fly over it and give it a shot.

And Tyler, I met because I posted on Facebook, Hey, if I've made an impact on your life, please let me know.

And he was going through depression and he's chronically ill. And he left a comment saying , thanks to the work that you've done, it's given me a new outlook on what I want my career to be.

I want to be a photographer. And so he bought a camera and he started teaching himself photography. And currently like today he's an award winning photographer.

So yes, it is possible to have an impact by just showing up and being who you are. And I think there's a lot of value in that. However, I wanted to make the bulk of the work that I was doing and not the exception to the rule.

And so those are three stories inside of a five year period of like my most impactful projects, but they only happened three times. And for me, I really wanted to find a way to make my career mean something more. And so while people could be inspired by the process of creating it, the final output of what I was making, the final photographs were just cool things cool for the sake of being cool.

And the interesting thing is when you do things that are cool for the sake of being cool or outrageous for the sake of being outrageous or difficult for the sake of being difficult, You eventually cap out. At what point does that become enough? And it never becomes enough.

You just keep trying to bump that bar higher and it's almost setting yourself up for a very frustrating existence.

Whereas I think in the existence of service of how might I serve and how might I help and how might I put my skills to good use is one that I find infinitely more interesting and more fulfilling.

It also gives me a little bit more strength when I am tired or don't want to wake up because I know that what I'm doing is serving someone and making a difference.

Ling Yah: Yeah, that was another thing I noticed .That not only do you want to serve people and it makes you feel alive, but that you are so accessible.

Like Nicole, she emailed it to you and she never expected you to reply, but you did. And all these other people, they reached out to you and you replied.

Even your blog posts, you, they just reach out and you reply. And I'm just wondering, do you not feel tired by all that? Do you not feel like you're constantly having to reply, having to serve. You're only one person.

Von Wong: It got to a point where it was really tiring I think, at the peak of my social career.

But now since my social famedom has sort of decreased, it's become quite easy. I welcome the little random emails and messages that I get. I really don't get as much as I used to in the past. And I think it's a byproduct of frequency. So if you post regularly, consistently all the time, people remember you, and if you don't, people have other things to think about.

And in my creation, I create these big spontaneous splashes and then those ripples just fade away really, really quickly these days. And so, it's actually become good. It used to be really tiring. Yes. But now it's become better.

Ling Yah: So speaking of ripples, you had your first big viral video in May 2014, which is the shipwreck shoot in Bali.

And it came about because your mom insisted on taking a vacation because you were just working too much, but then you ended up saying, oh, I want to do a dive course and just created this elaborate huge underwater scene.

The question that came to my mind was really how do your family react to that?

Von Wong: My family is really weird. So they complain about everything, but they're happy to participate in everything.

They never want me to do anything, but if I get it started, then they get excited and then they tag along for it.

So it's a really interesting thing. My mom's favorite word is no, it doesn't matter what you say. It's like, mom, let's go do X. No. But I haven't even finished saying what I wanted to do yet.

No, it's a waste of time. It's a waste of money. It's a waste of whatever. But then if you go when you do it, she'd probably come along.

And so I think with this Bali shoot, it's sort of similar in that, I'm like the weird person of the family. I'm like the Sheldon Cooper of the family, big bang theory.

And so like I'm generally, always up to something weird. I think my mom was just happy that I had said yes to go on vacation.

Now they were going to like to figure out how to keep me entertained.

And I think they also are fascinated in some ways, by things that happen. Like for all of their negativity or spoken negativity they are like one of the biggest supporters, right?

So every project I do, they're going to be there. Like when I did my mermaid on 10,000 plastic bottles, which was the day after my sister's wedding or they're cleaning bottles next to us.

When I went all the way to do my Guinness World Record in Vietnam, they went there to go and visit because they happened to be in Asia doing something else, but they took a detour to come and see the installation.

So my parents are always interested in seeing what I do. They're always complaining about what I do, but at the end they're also really, really proud of it. Like most recently we did these maternity photos of my sister and these miniature worlds out of fruits and vegetables.

And I'm submitting the story to the local news channel. And my mom is on the news. So my mom was on the evening news and I hadn't told her and she just liked watching and she was like, ah, that's me. And her first reaction isn't like, Hey, I'm on the news. Great. It's. Ah, I look so old. Why am I on the news?

Ling Yah: That's a typical mom response.

Von Wong: Yeah, but she's happy. Right? So she recorded it and it got sent around to the family.

So my family is kind of interesting that way. I think it's just the classic Asian thing.

Ling Yah: It's not quite classic when you have your own Instagram called Von Mon. That's really funny though.

Von Wong: Oh yeah. I'm kind of sad that we aren't communicating through WhatsApp as much, because that was just so much gold there because I could just screenshot the interactions that we have in our everyday.

Ling Yah: Let's just go back to Bali . could you just run us really quickly through how that all came together? Because that was something that was a turning point in your career?

Von Wong: You know, the funny thing is when I tell these stories, there is no reason why they should have been a success.

They're literally the dumbest projects ever that somehow work out. And I think for every successful project, there's a whole bunch of projects that didn't go through that no one ever hears about. So I guess there's something to keep in mind there.

But with the Bali project specifically, so my parents invited me to go on vacation.

I didn't want to go. And I was like, okay, what could I possibly learn during this time, which was diving. And as I started Googling what to do, if I got a dive certification, I noticed that there was a shipwreck and that if there was a shipwreck, then I really should do a photo shoot. And if I needed a photo shoot, then I needed a model.

If I needed a model, I needed costumes. If I need costumes and I need a camera and so on and so forth. So one thing really led to the other and I posted on Facebook. And this is once again, back in a time where Facebook, you can actually reach people saying like, hey, anyone knows someone in Bali that can help me with an underwater photo shoot.

And so a girl that I had never met before recommended another dive master that I had never met before, who agreed to meet me. And so I flew down. When we flew down, we organized a meeting with this dive master straight from the airport. So from the airport we showed up at this dive master's place, I explained what I wanted to do.

And it was like, so I wanna tie some models under water. I want to do this epic photo shoot. And he's like, okay. Uh, but you don't know how to dive yet? I'm like, no, I don't, but I'm sure it's going to work. Like, this is my portfolio. This stuff is going to do. He's like, okay. Um, do you have any models?

I'm like, no.

Do you have any like outfits? I'm like, no, he's like, okay, well, I guess we can see what we can do. So, because I was a friendly introduction and I had somewhat of a portfolio, he decided to just take a gamble cause he had produced underwater or photo shoots before.

And so I, you know, skedaddled and during this whole time while doing my diving certification, I was just kind of messaging people, trying to find models, trying to find makeup, trying to find like whatever I could. And it just so happens that this dive masters wife is an underwater model.

So she had access to some outfits, some wedding outfits that some guy was willing to donate for the cause.

Yeah, because they will be ruined after that.

Because they're ruined. They're one time use, except his underwater model wife couldn't hold their breath for long enough. So we actually needed free divers.

So then I went on this search for free divers.

And then this one girl that I had never met before, who had seen my work in the past, who liked my work, flew herself in from Dubai, someone else herself in, from Bali.

A makeup artist who knew the dive master came on board. And then suddenly, like we had this like little crew of people to do it this thing in,

all I had to do was pass my diving lesson. And so as I was doing my dive certification and we had to do our different tests, I convinced my dive teacher to do our examinations in the place that I was going to do the dire so that I could do scouting right the same time.

So I had a little GoPro and I was going around. Yeah. And I was taking pictures of the places that I thought could be interesting.

Something else that I had brought was a little consumer underwater camera. And I've always felt like if you used equipment that was not professional, like lower caliber equipment, it was more relatable.

And so I had gotten this cheap little camera that I wanted to use but I ended up breaking it. I flooded the whole camera. So the day before the photo shoot, after having collected all this stuff and this girl who was like gonna fly over and stay on the sofa, I didn't have a camera. And so I reached out to the dive master again, and I'm like, Hey, I need help.

Do you know anyone that has an underwater camera? And so we managed to get another camera. So anyways, one thing led to another, we eventually had all the pieces. Yeah. And then from there, all we had to do is actually do the project.

I was trying to get someone to come and document it because I knew the power of behind the scene videos and a guy who had just taken my photography workshop in Singapore, flew himself down to document this.

And he rented his own underwater housing because he wanted to learn how to shoot underwater, but he could only make it for one day. So he flew himself down just for a day, just to shoot this thing and flew himself back. And that video that he made ended up being the thing that went totally viral and it was trending on Facebook back when Facebook was trending and it just blew up all over the internet.

And then suddenly I became an underwater photographer, cause I had done one underwater photo shoot that was super successful.

The reason why this project went viral and my other ones didn't I think is because this photograph was able to be described in words, right? I could say. Photographer ties model 30 meters underwater in a shipwreck in Bali.

Even if you can't see the photograph, even if you can't touch the photograph, you can still understand that it's something that might be interesting. And so now you want to go and see how it was done, and the fact that I could describe my photograph into words for the first time in a compelling way, I think is really what got it to pick up along with the behind the scene video.

Ling Yah: So that's two questions I wanted to ask . And firstly is really the fact that all these people came together on the strength of who you were as a person, they flew in. And do you have an idea of what encouraged them to fly all the way from another country just for this one day,

Von Wong: I think people want to touch the extraordinary, right?

People want to be a part of something cool. That's unique and different. And once in a lifetime. People pay money to do that.

And if you can offer them the opportunity to do that without paying money by just being who they are ,how often is holding your breath for a really long time, the most useful skill necessary for our project?

To be able to use who you are as the key ingredient to make something impossible possible, and to be able to touch upon that, I think is a really powerful feeling. And so when I ask for help with volunteers, I try to really make it about the experience of doing something that they could have never done otherwise.

And to be a part of something greater, to be a part of something really big to be a part of like a movement. And I don't know how to do that remotely, right now.

So I don't know that skillset translates when you go away from physical experiences, but that's how I've traditionally done it in the past.

Ling Yah: And I remember hearing you say once that people don't pay for content, but for transformation. So clearly that's the kind of thing that you were offering then. Transformation. And you were also very interested in how things went viral.

You really went on this whole exploration trying to recreate that kind of reality with like superheroes of a 40-storey building, like the Sutro Bath with a girl and a big feather costume, even Admont Abbey.

What was interesting for me is that you really deep dived and analyzed why they didn't go viral. I was wondering like at the end of the day, do you know what it was?

Von Wong: The most important thing is the title. If you don't have a headline, no one's ever going to open the email. No, one's going to click on the link.

No one's going to be compelled to take their time, which is the one thing that no one can get more of in order to do.

Clickbait used to be a big, big thing until like all the platforms started canceling out their potential. It's like there are certain headlines that are very, very compelling. And if you can create a compelling headline, I think it makes a really, really big difference.

Similarly, I think it's less about the photograph. People focus a lot on the final result, but the process of how you get to something is often more interesting than the final product itself, because the final product when it's something that's really, really cool. It just feels out of reach for most people.

But if you break it down and you make it feel like it's possible, you make them believe in their own potential to do something only they wanted to take the chance. Like, I think that's a really empowering feeling. There are other ingredients that are really important, depending on the platform you're in, the way you structure content is very different.

Like the first three seconds of a video on Facebook with autoplay is really important. A thumbnail on YouTube videos is really important with SEO. So like, it really depends on how far you're willing to go to optimize things. But ultimately if you are really just trying to keep things simple, do something that evokes curiosity, do something that adds value to a person's life.

Don't think about like, Oh, I want this thing to be seen. Think about how well this thing that I am creating improves the life of the person who's watching it. And if you put yourself in that mind frame of giving an offering and adding value, I think the basic approach in which you tell a story will change.

And it will be better and it will be more compelling.

Ling Yah: And so the next big thing for you, I mean, these are all lessons that you've come to after doing all of these videos, but at the time you were focused on just creating great content for people and you ended up with Huawei, but there was something that was a big turning point for you as well.

Could you share why that was?

Von Wong: Yeah, I mean, the dream of every creative is to get paid, to do what you do best to get paid a lot of money to make a living off of it. And for me, that moment happened in 2015. When Huawei hired me to be like the face of their 2015 campaign and invited me to take the most extravagant photograph possible with the cell phone.

And so I created this campaign and it paid me more than my entire career combined.

When you think about that, it's sort of like the Mecca, right? The Holy grail of getting paid a lot to do something you enjoy. For me, it had the opposite effect. It showed me what it meant to be at the top. And it felt a little bit empty, a little bit boring.

Like if it's just money without purpose, then what have I actually accomplished other than helped a big company sell more products and put dollars in my bank account. Like it just didn't feel like enough.

And I think the fact that I got there so quickly, within three years or so of quitting my day job just exacerbated the problem because if I had spent like three decades working for this goal.

I think it would have been a slightly different reaction. Because I got there quickly, I just really second guessed like, wait, well, this can't be the end.

This can't be the rest of my life. I don't want it to be the rest of my life. It just made me really contemplate my career.

And actually it almost invited me to quit photography because at the time I was like, okay, well, I just do fantastical things with my photography, but like all my impactful projects were all some form of documentary. They all involved making a video. So I actually took a pause from photography, went off into documentary filmmaking for a little while, realized that just telling sad stories of people who are struggling, wasn't really my jam.

And then kind of tried to figure out how to combine photography and documentaries together.

Ling Yah: So how did you figure how you were going to combine it? What was that turning point then?

Von Wong: it wasn't so much a turning point as much as just a constant series of experiments and failures. It was a super frustrating experience because when I decided to do impact stuff, I thought it was going to be a walk in the park, right?

Like I have a really great portfolio. I've earned money. I've, you know, have a following. I thought I could just go and knock on the door of different nonprofits and say like, Hey, I love what you do. Let's figure out a way to work together. I'll work for you for free.

But it just doesn't work that way or it didn't work that way for me. Just because I was willing to offer my time didn't mean that they saw the value in it because I think nonprofits especially are very risk averse.

They don't want to take risks. The work that I do is super risk prone. Everything I do is risky because I want to do things that I've never done before. So there was just like an intrinsic incompatibility between what I did and what nonprofits want. And finding the ones that were willing to take the time to flesh that out was really, really difficult.

I spent a lot of time trying to work with different people and it just wasn't going anywhere. I eventually just gave up and started focusing on what I could do.

So I know how to gather people. I know how to do crazy things. Like what are some causes that are worthy of attention and how might we tell those stories?

And the first one that was really successful was my girlfriend's idea, actually. See, girls.

Ling Yah: Another turning point.

Von Wong: Yeah. Huge, huge impact on my life. So this is the girl that I'm still with now.

Anna has always been a little bit more of an environmentalist than I am.

She's a total hippie.

She's a photographer. And let's take a little pause here to talk about Anna real quick.

I was creating content to inspire other people.

Tyler was one of those people that was inspired. I ended up going to surprise him for his 21st birthday cause I knew it would mean a lot to him. I put a video out into the world.

And then Anna sees this video, who's now my girlfriend. And she comes up with the idea to use storms as a metaphor for climate change, which ends up being the first environmental project that I do, which then kick-starts me onto a career path that has resulted in me being an environmentalist.

It's really weird how different dots connect in life. It's not a story that someone could even plan out, but it's happened in that way, which is really cool.

So, yeah. So Anna came up with the idea of using storms as a metaphor for climate change.

She really was just looking for an excuse to go storm chasing because it just sounded like a really cool thing for us to do as a couple, but I didn't want to do anything that didn't have a cause.

So she came up with the cause and the idea of putting ordinary people doing everyday things in front of these big billowing storms.

I found a storm chaser called Kelly delay, as well as a fan who had an ambulance that was willing to come with us. And we used the ambulance to store all these props and stuff inside of it. And so that just became an entire campaign, which, you know, in my portfolio, wasn't a very successful visual piece.

It was definitely not my most beautiful work, but it gave me a sense for the first time that environmentalism, which is something that's very abstract, might need a little bit of fantasy to kind of explain certain things. It allowed me that little hint that something like this was actually possible.

Ling Yah: So you had that hint, but then the next few months, nothing really came about did it?

Von Wong: Well it just takes time, right? Because every project takes so much time. So you need to find the cause, you need to find the right people, you need to find the right place. Like all these different stars need to align. And so I just kept an eye out for different projects.

Every time I went somewhere. It's, you know, once again conversations are my thing. I just start talking to people and ask them like, what is there to do? How could I take an opportunity and transform it into a new direction? And I was invited to teach a workshop in Fiji.

And I was like, okay, well, if I'm going to go to Fiji, what can I do there? I started talking to some friends and they were like, Oh, Fiji has some really great shark dives. I'm like, Oh, sharks. That's cool. I know like shark fin soup is a problem. Maybe I can do something around like protecting sharks underwater.

And so I bought a shepherd crook on Amazon which was 20 bucks and I just flew to Fiji with this thing. And I was like, okay, now I just need to find someone who will teach me how to dive with sharks.

And so in the middle of this workshop, I'm there hunting for someone who would give me access to a shark dive because I already had a model because I had already done some underwater stuff. So there were freediving models that wanted to do something.

I had found a videographer that would be happy to fly over and document it for free if I pay for his plane ticket, and, you know, spent five days trying to get connected to the right person and eventually got lucky.

A fan knew a person who ran an eco resort who had a shark scientist. You know once again, another story that should have never worked out, but it did.

And we ended up creating a shark shepherd. So we tied the model underwater. This time of sharks swimming around and trying to raise awareness for sharks because every single year, a hundred million sharks are killed.

And I think that was like another big success. It hit the front page of Reddit three times, it got 80,000 petition signatures and gave me more signals that there was potential here. I still had no idea how I was going to earn money doing this.

Still didn't break down more doors for me to work with other nonprofits, but I just kept poking away at this thing.

So I just think that really these projects, there are no logical connections. There was not so much of a plan as much as a conviction that if I poke away at this for long enough, at some point something's going to give, because I know the work that I'm doing is good.

I know that there's no one else doing this. I know that it's interesting. Somehow I'm going to have to be able to make a living doing this. I don't exactly know how, but I just have to have faith that it all worked out.

Ling Yah: So I'm sure that you weren't sitting on your laurels waiting for these opportunities to just drop on you. So how do you go about just encouraging those kinds of opportunities or options to come to you?

Von Wong: I don't think they manifest as opportunities as much like really just being curious and having conversations, right?

Like everybody knows somebody doing something cool. And if you keep all that information and intention in your head, then no one's ever going to discover what it is you're actually interested in, right?

But if you go out and you're like, Hey, I'm going to be going to, to this place. What can I do? Or I'm really curious about this topic, do you know anyone that could help it and you just keep pulling on those threads, like, keep asking those questions. At some point, you know, something is going to happen.

Let's flip this around at the time I was doing maybe three projects a year.

And in order to do those three projects a year, I was having a zillion conversations that were going nowhere. But those zillion conversations, out of the ones that go nowhere, you only need one to go somewhere . And you also don't know if it's a conversation today, that's going to lead to your project that's going to happen in five or 10 years from now .

So it's all about planting those seeds and getting out and just believing that it could go somewhere. It doesn't even have to go somewhere, but it could go somewhere.

Ling Yah: So how did you decide what could go and is worth pursuing as opposed to the others that you can just drop?

Because I mean, all the things that you've done are actually pretty, some might say crazy. I mean, like chasing a storm, and putting your life at risk. I swim with the sharks, I'm finding someone who's willing to do that and just bringing all those incredible elements together into that one perfect storm.

Just like saying, it seems like the odds were against you. So how did you even decide what you could go for and what you couldn't.

Von Wong: I mean, I chase the story. I don't chase the possibility or impossibility of it. I knew that diving with certain sharks is not dangerous at all. And I think that's just a misconception, which is why it makes it a good story.

Similar to storm chasing. If you go with someone who understands the way storms move and who's cautious about it, then there's really no danger. Cause yeah, a huge part of every single one of these projects is risk mitigation. Is making sure you do things safely.

What I play with is this notion of fear versus danger, right?

Fear and danger aren't always proportional. Just because you're scared of something. Doesn't mean it's life threatening.

And similarly, if you're not scared of something, it can still be very life threatening. So it goes both directions and I like to play a little bit with that distinction because what you notice that spreads well on social media is emotional responses, right?

People will make decisions emotionally, not logically. And if you can tap into people's emotions, if you can get people to feel something, then you have the ability to communicate something with them.

And in my case, as sort of, I guess, an activist. That's what you try to do. You try to communicate messages but no one wants to hear how the world is broken, right?

No one wakes up in the morning and goes like, ah, I just want to hear about how screwed up the world is. People want to hear about something beautiful, something cool, something inspirational, some new sense of possibility. And I think art has the power to do that, right.

And so I get the chance to create these opportunities for conversations so that people have the courage and the fortitude to move forward on the issues that actually need to be tackled.

Ling Yah: And do you think the emotional part, that was the reason why the mermaid project was so successful? I mean like to date, it's got 37 million views, which is quite a tremendous amount. What made it so exceptional compared to all the others that you were doing?

Von Wong: The power of the mermaid picture that I did, which is a mermaid on 10,000 plastic bottles, is that it doesn't need any words to be explained. Whereas a lot of my other work actually still requires at least one sentence in order to frame the problem or the solution or the situation.

With the mermaid on 10,000 plastic bottles, it's a combination of beauty and sadness at the same time. And I think what makes it so powerful is that it actually creates polarizing emotions at the exact same time. It's like a visual thing paradox. It's like your childhood and fantasy bundled up in the reality of today and where we're headed.

And I think that because it strikes at such a primal level, like everyone's encountered a mermaid, regardless of which culture that they're a part of. Everyone knows what a mermaid is. And you don't look at mermaids as a grownup. You really look at mermaids when you're a kid. And so there's a sense of like your childhood dying and drowning in a situation that's present that I think hits every single age category and demographic at the same time.

I think that's why that one was successful. And in addition to having a great title, right? Mermaid on 10,000 plastic bottles, dying mermaid on 10,000 plastic bottles, mermaid drowning in 10,000 plastic bottles, it's like it could be rejigged, reshaped in any number of different ways.

And then when you hear that, Oh, actually 10,000 plastic bottles is the average number of plastic bottles, a single American might use over the course of their lifetime. They're like, Oh, this is one person's plastic bottles. Oh, these are my plastic bottles. I think that adds to like that emotional pressure.

And finally, I think the video is just well made. Like the video was well shot. It was interesting. It was evocative. It was humble. I think it just hit all the right emotional tones. It was the right time. I think timing always plays a really big role. This was right. This is before fighting against plastics became trendy.

This was right along the time where the great Pacific garbage patch was just starting to get attention. And it was right when Boyan slat, the kid who wanted to come clean up, the oceans was just getting a lot of attention. So it was the right time and it was a place in which like artists hadn't really started playing in

To take something ugly and transform it into something beautiful was not that common. Now, today we see a lot of trash art. It's super trendy. So once again, hard time to stand out, but if you're doing it before it was trendy, right at the right time and the right place, then I think you had a lot more opportunity.

Ling Yah: And is standing out something that you do concern now that you're more into the social impact space?

Von Wong: I think standing out is super important because ultimately, if you are an activist, then you're driven by the outcome. You want to transform people's perspectives on something. You want to change a policy. You want to change the law. You want something to change.

And if no one sees what you do, then how are you going to change anything, right? it has to be shareable. You have to create for others, you can't just create for yourself. And I think that's actually something that's really tiring from a creative perspective because you lose a lot of the joy of the place process of creating when you're creating something only for the outcome and the output.

And so while I recognize the necessity of it, I also think that we need to acknowledge how hard it is.

Ling Yah: So, you've gone through so many different things and now how do you see yourself? Do you see yourself as an activist? Cause at one point in your podcast, you actually said I'm not an activist, but people consider me as one.

On your website, you don't consider yourself an activist, you call yourself someone who wants to amplify positive impact, but then other places you call yourself just an artist so who are you? How will you describe yourself today?

Von Wong: I think I'm just a man. I'm just a person trying to do the right thing to the best of my ability.

And I can be one thing relative to another thing, right? So measure it against the average person. I'm definitely an activist because I'm dedicating my life to supporting positive change, like compared to an activist that is on the ground. Dedicating their entire life to this one, single cause I am nowhere close to an activist, right?

So it's a relative term. And I think people just have to put you in boxes and I find it helpful to myself in a box for others to understand what I do. So if I say I'm an artist and an activist, it doesn't explain the full spectrum of what I do, but it explains enough. People understand that I create creative things.

And that I also create creative things to bring about positive impact.

So I can summarize sort of who I am in two words, even if they're not exactly the right words. And that's just a problem that I've always faced, but yeah, who am I?

I'm just a dude trying to do the best that I can with what I have to make a difference in the world.

Ling Yah: I think it's also very human that we also want to have some kind of a metric of success, even though we say we want to have some kind of impact, we do want to try and measure it. So do you have some form of measurement for yourself?

Von Wong: Yeah, metrics of success. This is the reason I started my podcast called Impact Everywhere, with the intention of trying to measure positive impact in unexpected places. And it was driven by the realization that if you don't better measure the impact of art, then you'll never be able to sell the impact of art. And if you're never going to sell the impact of the arts, then no one's ever going to hire you to do it.

And it's less about me making a career and more about others making a career. Like I think that the arts have such an important role to play in shifting culture and hearts and minds of people. And it's currently not being leveraged or used because all the most talented artists are being sucked by marketing companies and entertainment companies, because that's where the money is.

And so how can we shift the paradigm of what good art is from the price someone is willing to pay for it, to the amount of good or change it can bring about in the world. And so that was the premise upon which I started the podcast.

I think a lot of my success when I talk about my work is all quantitative.

It's about the number of followers I have. It's about the number of views that I've gotten. It's about the number of awards that I have one or the companies that have hired me. It all depends on this sort of external recognition of like numbers. It has absolutely nothing to do with what I've changed.

So measuring the impact of art in its entirety, it is likely really really far away. I don't think it's really possible at this stage. However, I do think that if we design our projects better to consider what we're actually trying to measure. We can actually measure more of the impact than we currently are. What we hear in popular culture is that the role of the arts is to touch people's hearts.

But how are you going to measure touching someone's heart, right? If that's the goal, you're never going to think about how you're going to measure it. And so it becomes a lot more conditional. And so one of the things that I've noticed as a result of interviewing other people and asking them how they think about impact is that impact takes place in two different places.

It takes place in the process or in the output. So the process of creating art, let's say you're bringing PTSD veterans together to paint something. And in the process of bringing them together, they find a place of community, of belonging, of safety, security, and they become more peaceful and productive human beings?

That's the process of creating. So it doesn't actually matter what they create. Doesn't matter how good their art is. The fact that they're coming together to create something is the impact that you're looking for . And so if you design your entire program around measuring the transformation, the people, then you can measure the impact of art.

The other way to measure sure is through the output. So output is I've created this piece. What has the piece done? So if you tie your piece to a state change, and I think this is something that I have failed to do, and something that I was planning on doing prior to COVID-19 was to actually try to reduce the size of the Petri dish.

So instead of trying to change the world, try to change like your neighborhood, try to change your school or try to change your family members.

And if you can create something that works at a small level, then maybe it'll work at a bigger level. So start with something that you can measure, or that you can create a container of measurement around.

And sometimes that just means that you have to start with a measurable environment in the first place. If you measure the effectiveness of art within a hospital, then you can actually measure how quickly people heal, how long they stay, how much medication they use, because you're in a measurable environment.

I'm really trying to understand the mechanics of impact so that other people. Can pursue a career in it, because if we don't create the opportunities for people to pursue jobs and careers inside of the impact space, and they're not going to do it. They're going to do something else.

And then they're only going to pursue impact on the evenings and weekends when they have time or with a little bit of money, they have to donate. And that's not how we're going to fix the world.

Ling Yah: Do you never worry that because you have gone on this path, that you are alienating yourself or potential clients and not every artist might be in that position of being able to say I have a cause and I want to dedicate myself to it. But actually, I can't afford it.

Von Wong: There's two ways to think about the exact same problem. You can be like, oh, if I embark on this lifestyle, I'm going to have to lose all these other opportunities.

But think of all the opportunities that you're going to gain as a result of pursuing this lifestyle . all the places that you meet. Other people that you'll meet that are like minded, all the conferences that you might now attend, because you're a hundred percent committed to learning more about this cause and so on and so forth.

There's this awesome talk by Alan Watts. He is like a dead philosopher that says what if money was no object? And in the piece, he goes on and says like, it doesn't really make sense to spend 80% of your life doing something that you really don't like, just so that you can spend 20% of your life doing something that you really enjoy.

And if you never find something that you really love that you're willing to get better at, that you're willing to invest time and energy and effort into ,then no one's ever going to want to pay for it. Right. I think it's sort of a double edged sword. Like someone needs to take a risk at some point.

Ling Yah: Have you ever found yourself alienating potential clients simply because you wanted to pursue this path of social impact?

Von Wong: Yeah. When I decided that I was going to pursue impact for a year, I basically turned down every job that came in. That wasn't willing to incorporate impact into whatever project we're going to do. Sometimes I was successful in converting my clients.

In my project with Nike, where we hung athletes on the edge of a 30 story skyscraper or something, they reached out to me and they wanted to use influencers.

And he said, no, but can we use social impact entrepreneurs instead. People that you sponsor, people who are doing good in the world, instead of people who are just chasing fame for the sake of chasing fame. And they said, yes, why? Because it made a better story. Right? So I think that there are people in the world that you can convince to do the right thing.

And I think it's actually shifting nowadays, like this whole idea of the purpose economy is something that's really, really growing. Everyone is chasing after impact. Everyone's chasing after authenticity. There are so many consumer studies that have been done that show that it is more important for a company to believe in something than to believe in nothing.

And so I think consumer opinion is slowly shifting and an impact is mattering. And we see it in the jobs that people are looking for. We see it and the urgency of what the world needs in order to change. We see it in a lot of the social media outrage and the polarization that's happening. Like people are just crying for it.

So while I do think it's a harder path, I think it's a more rewarding path.

When I think about my career as an environmentalist, the content that I create is evergreen. The mermaid on 10,000 plastic bottles just recently got put on a stamp for the United nations. And it wasn't because it was a pretty photo.

It was because it was a photo that stood for something and it's standing for something that's not going to go away. And so actually for so long as plastics is a problem, my photograph is going to be relevant and it will continue to be used.

Whereas if I just created something that was cool and that was pretty, it would never resurface again because there's no reason for it to resurface. Again, there's no reason for someone to talk about it again, but now when you do art that stands for something. And that thing is a continuous problem. It'll be evergreen. And I think what better than to try to embed yourself in the history of positive change in the world that the world needs.

Ling Yah: Looking back, is there a particular piece of project you've done that you're proud of?

Von Wong: So I struggle to answer that question because every project is unique and every project is different. I don't create for myself, I create for the impact that it's had on the world. But because I haven't taken the time to measure the impact or I haven't figured out how to measure the impact, it's actually a question that I really, really struggled to answer.

I think less than a project. I think I'm just really proud of my direction. Of the fact that I chose a direction. I stuck to it. And. Regardless of what's happened, I've always found a way to recalibrate and adapt to it. And I think we might want to look at life less as a destination as just as much as a series of journeys that are pointing us in a direction that we find encouraging that we find empowering that we are proud to live.

Ling Yah: And where do you think your journey led you, especially in this COVID-19 period?

Von Wong: I don't know.

I am currently a 33 year old unemployed man, staying at home with my family in Montreal. I was planning on being nomadic this year and I had gotten rid of my place in San Francisco. And now I'm grounded.

My girlfriend lives in Australia. I have no idea when we're going to see each other next because borders are closed and the entire industry that I serve which is basically the events industry and the movement that I serve, which is the environmental movement have both completely disappeared.

The way I earn money is through speaking engagements and consulting and installations, all of which are gone right now. And so I have to say, there was a period of like grief. I think of sadness of wondering like, Oh, what do I do with myself? What am I good at? Who am I if I can't do what I do best, I think it took me about like 10 days, 10 days to get through that.

And now I'm kind of excited again.

I'm excited because I have a blank slate. I think for a very long time, I was feeling bogged down by my success in that. When you become successful, people have a lot more expectations of you. And now I no longer have my success as anything I can offer to people.