Powered by RedCircle

Listen at: Spotify | Apple Podcast | YouTube | Stitcher | RadioPublic

Welcome to Episode 129!

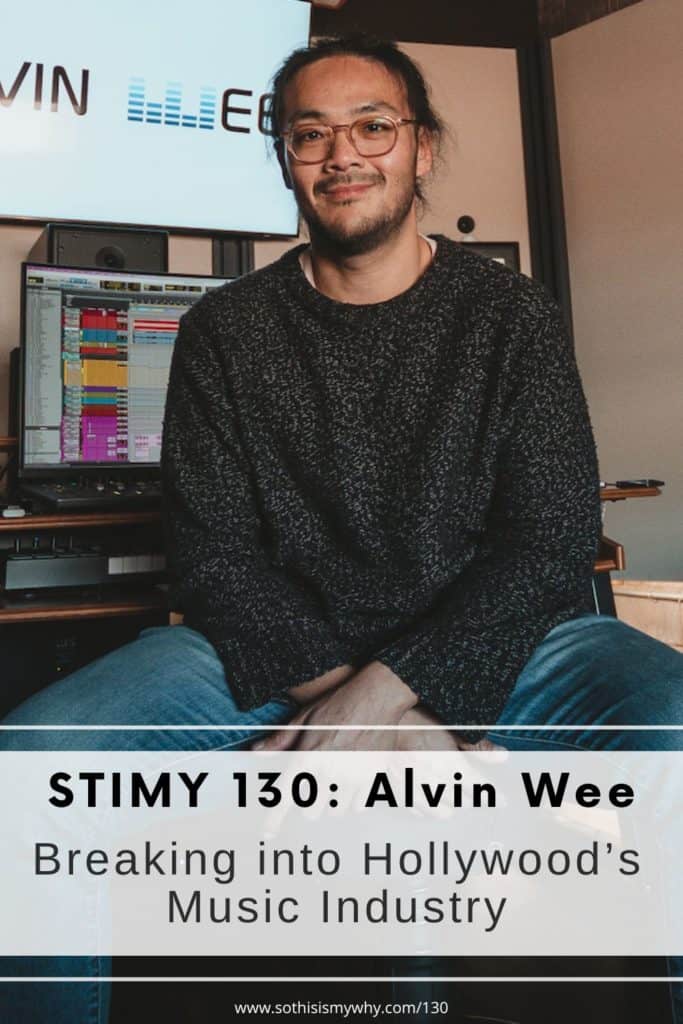

STIMY Episode 129 features Fabien Riggall – founder of Future Shots & Secret Cinema.

Fabien has always loved films and began his career working as a runner before becoming an assistant producer of short films.

In 2003, he set up Future Shorts: A series of mini pop-up film festivals that took off in 2003.

That eventually evolved into the creation of a skate park under London Bridge, where around 400 strangers showed up to become part of the skating community & be part of the murder mystery story!

Secret Cinema is premised on the idea that films can be turned into large-scale real life, cultural experiences in abandoned spaces.

The location and details of each World are never reveled and the film title is often kept secret (the reason for this was that it was entirely by accident!).

Secret Cinema grew into such a phenomenon that it eventually sold to TodayTix in 2022 for £89 million!

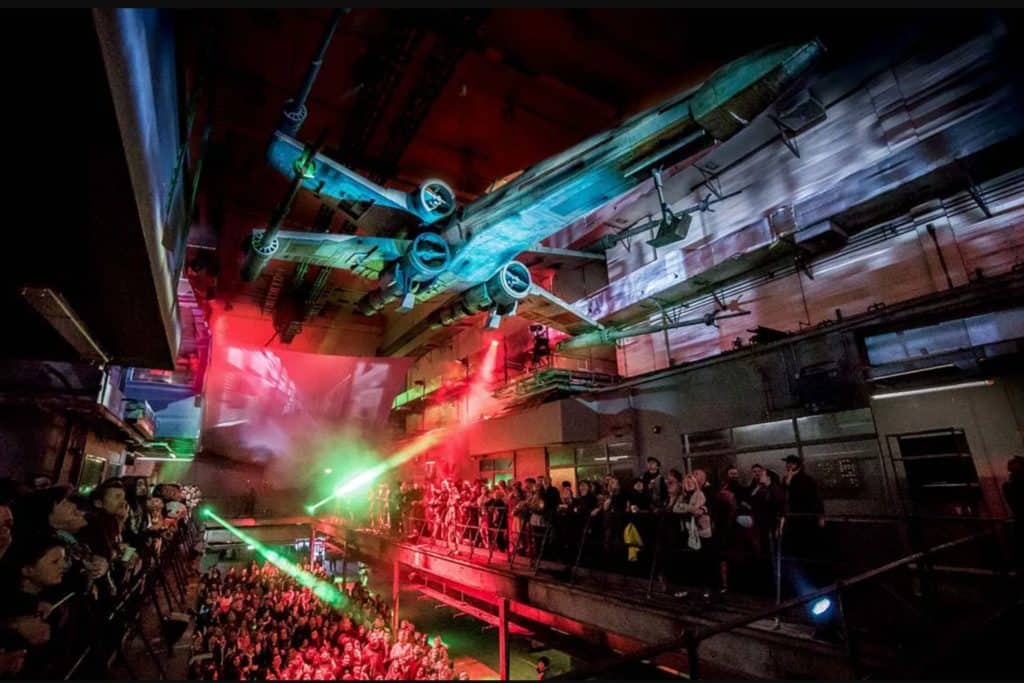

And some of its most famous works include: The Great Gatsby, Star Wars The Empire Strikes Back, Blade Runner and Moulin Rouge.

If you’re curious in learning what it takes to build a whole movement & transform the way people see and use abandoned spaces while bring film to life on an epic scale, then this is certainly the episode for you!

PS:

Want to be the first to get the behind-the-scenes at STIMY & also the hacks that inspiring people use to create success on their terms?

Don’t miss the next post by signing up for STIMY’s weekly newsletter below!

Who Fabien Riggall?

Fabien Riggall spent a great deal of his childhood in Morocco, which is where he also discovered a love for the cinema. Which eventually led him to film school although his first experience with work was… not too great, to say the least!

- 4:31 Morocco

- 6:41 Becoming a farmer and an actor?!

- 7:43 I don’t want permission!

- 11:23 Running festivals

- 12:13 Soul-destroying work

Secret Cinema

Secret Cinema grew from a tiny production underneath London Bridge to the behemoth that it is today, e.g. building large-scale X-Wing fighter jets for its Star Wars production or transforming an underground basement into a full-on Moulin Rouge party.

- 15:45 Leveraging the internet

- 16:57 Selling out a murder mystery event at a secret skate park under London Bridge

- 19:47 Finding the right people

- 23:45 Pushing the boundaries

- 30:14 Building trust via newsletters?!

- 32:59 A limit to provocation

- 36:54 Maintaining your voice

- 39:28 Biggest battles waged & won

- 43:32 Stepping away from Secret Cinema?!

- 47:01 Achieving everything that Fabien wanted?

If you’re looking for more inspirational stories, check out:

- Justin Byam Shaw: Co-Owner of the London Evening Standard & the Independent – on building a media empire in the UK & US

- Eric Sim: From son of a prawn noodle shop owner to former-MD of UBS with 2.9 million LinkedIn followers

- Apolo Ohno: The Most Decorated US Olympian in History – on the power of psychotic obsession & how to win in 40 secs

- Lydia Fenet: Top Christie’s Ambassador who raised over $1 billion for non-profits alongside Elton John, Matt Damon, Uma Thurma etc.

If you enjoyed this episode, you can:

Leave a Review

If you enjoy listening to the podcast, we’d love for you to leave a review on iTunes / Apple Podcasts. The link works even if you aren’t on an iPhone.

Patreon

If you’d like to support STIMY as a patron, you can visit STIMY’s Patreon page here.

External Links

Some of the things we talked about in this STIMY Episode can be found below:

- Secret Cinema

- Subscribe to the STIMY Podcast for alerts on future episodes at Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Stitcher & RadioPublic

- Leave a review on what you thought of this episode HERE or the comment section of this post below

- Want to be a part of our exclusive private Facebook group & chat with our previous STIMY episode guests? CLICK HERE.

STIMY 129: Fabien Riggall (Founder, Secret Cinema & Lost)

===

Fabien Riggall: It was pretty soul destroying. The main premise was it was Euro News, which is a channel, and you had to sell editorial to CEOs by saying that you're doing an interview with them to highlight their amazing career and by the way, it's gonna cost 20,000.

But in order to get through to the CEOs, you had to research the stories of those two CEOs just like you do. And then we had to basically pretend that we were this big editorial organization. So I would have multiple assistants.

It was just a hustle.

When I ring up, my confidence was just a different thing, was just like, yeah, I'm a producer. I've got an extraordinary film project. Can't tell you too much. A lot of people are interested about it. And it was just a hustle. But what it made me do in my own mind was, I'm not trying to be a producer. I am a producer.

And just that statement, which I would recommend to anyone, whatever they want to do, is that it's a total hustle. It's a myth. The whole thing is based on what you say you are, you become. What you want to create, you create. It's just whatever you want it to be.

Ling Yah: Hey STIMIES! Welcome to episode 129 of the So This is My Why podcast. I'm your host and producer Ling Yah and today's guest is Fabien Riggall.

Fabien is the founder of Future Shots and Secret Cinema, which is a London based entertainment company that specializes in immersive film and television events all the way back in 2007.

Secret Cinema essentially takes popular movies like Moulin Rouge, Dirty Dancing, Guardians of the Galaxy and Star Wars. and brings them to life. Now, I personally had my own experience with secret cinema years ago, where I essentially bought a ticket for a time and date and knew nothing else. In the days leading up to that particular event, I was told what to wear to be in character and also where to show up and again, nothing else beyond that.

On the day itself when I showed up, I found out that secret cinema had actually taken over an entire office building. decorated and turned into the site of an alien invasion and filled it with hundreds of actors and actresses. We spent the first few hours of that evening just visiting every floor, interacting with all different characters and even leveling up in office politics, which is very similar to the movie itself.

And by the end of the evening, there was this epic showdown between all the characters in the central courtyard. And to be honest, that remains one of the most memorable experiences I've ever had. I was Really blown away by the sheer effort and the creativity that we acquired to pull it off.

And I just thought, I really want to know who came up with this idea and what it takes to pull it off. So I'm really excited to share Fabian's story because he is the person who came up with this idea. Build it to what it is today and he's going to share his entire journey as well what his future plans are.

Are you ready?

Let's go.

Fabien Riggall: I was a terrible child.

When I was young what I became good at was disruption much to my parents' and to my teachers' dismay. I was kind of always challenging and always curious about what wasn't there or what, how I could provoke reactions from teachers and things.

So I wasn't the best student, but I was always very interested in drama and theater when I was a kid and films. And So I was quite an unruly child, I would say.

Ling Yah: It was interesting when you're talking about Unruly Child. It reminds me of an episode I just released, and he's actually a lawyer, the president of Singapore's Law Society, and he said that in person, I'm scared of speaking out, but then in writing I write subversive books and I'm always going against the norm.

And he found that he had to, he was unable to do it in person, but he could do it in writing. I wonder if you were willing to just add out and say, I don't believe in this system.

Fabien Riggall: I mean, yeah, I think I just acted out when I was at school not obeying rules. Doing the wrong things.

That was my way of acting out, I guess. Or provoking or being subversive to the system. I didn't really believe I was in a very strict upbringing in a boarding school from the age of seven in, you know, quite a privileged setting. And yeah, going to school away from your parents at seven.

I think I was just doing things that were making statements around what I thought about things, but also I was just an annoying child probably to them. They were trying to keep the rules.

Ling Yah: How did you end up in Morocco when you were 10? Because wasn't that when your interest in cinema was sparked.

Fabien Riggall: Yeah. My father worked in the finance as a banker and he got posted out to Morocco.

So, you know, aged I think nine when I first arrived there, I was still at boarding school, but I'd spent all the holidays there.

That was a big part of it, right. Moving into a place, which is so unreal and nothing like the culture that I'd experienced before just opens your eyes as soon as you get out the airport.

The city of Casablanca was on one side, a kind of commercial metropolis. But there was this other side of it that was su and very traditional arab culture. and I think that opened my eyes just naturally to this other world, this other reality.

The beginning when there was no DVDs, it was all VHS tapes, and no good television, so we would get all these films on VHS sent from England. So we would have all these films and TV programs coming from England, but on these VHS tapes.

So I sort of get really interested in movies from the age of nine. And then I would go to the cinema with my father and parents and it was always just this kind of magical escape. This romantic thing.

I didn't think it was romantic at the time. I was 10 years old.

The combination of living in a country in a culture, not understanding that culture and then going to the cinema.

One time I went for cinema without permission. Went to the cinema, which was like a mile away, walked in, bought a ticket, didn't know what the film was, didn't understand what the film was and it was once upon a time in America, Sergio Leoni and this beautiful kind of epic violent gangster film where the lead character was sort of my age. And I suddenly, I think in that moment people were smoking in the cinema. It was practically empty. And it's just those moments you have in the cinema or you listen to an album or whatever.

But when you just have this moment of trans fiction, you know, just feeling so involved in the story that I think at that moment sort of fell in love with cinema and fell in love with the idea of cinema. I created my own reality within it and was quite obsessed with going to the cinema from that moment.

Ling Yah: Was that when you started thinking, I want to be an actor, producer, because you also wanted to be a farmer, which seems like came from nowhere as well.

Fabien Riggall: So my father is a farmer originally. That's how he started before he realized he needed to make money.

We have a family farm on the Isle of Man and so farming has been in my family. But I think that was the moment, yes, that I got really obsessed with cinema and then I used, was always interested in drama. So there was this sort of love of cinema and drama.

And then I would go to live music, to concerts and then being the slightly rebellious child would go to legal parties and gigs. When people ask where the secret scenario come from, it comes from that sort of illicit, decadent, slightly naughty world of free parties and raids and this sort of idea that you could be anything and you could go to one of these nights and let go and they weren't legal these nights.

So there was this feeling of breaking the rules. Just something that's important, I think as a growing teenager, to sort of break the rules a little bit. um,

Ling Yah: You sounds similar to some of my Street artist friends who would say, we would never paint a wall if we have permission.

That defeats the whole point of it.

Fabien Riggall: The world is this sort of sense of the power structure. Especially now with culture, has eliminated perhaps the ability for radical movements to take shape. Like all of the artists that used to do the trains and the subways and the tubes and all these things, they're all painting walls in London and New York and these places for corporate brands.

In a way that's how you make money. And I would say that a lot of my friends who used to either run magazines, like I have a friend called Bertie, who ran a magazine called Mush Pitt. There was a sort of satirical Vogue, which she created all her own advertising, her and her partner.

It was like this sort of disruptive fashion magazine and it was really beautifully made and created and yet, it was impossible to earn a living from running that magazine.

And she refused to put advertising in it. She would put fake advertising to provoke and satire the other advertising.

But she's earning good money working for the advertising industry and so are so many of these people. So many artists are in that place. I'm rambling on, but the point I'm making is that, I think that with arts there is a whole opportunity, especially now in the times that we live in for artists to take a stand and to regain certain powers. Away from the system of oppression.

Ling Yah: There suddenly seems to be a kind of global wave of everyone rising and saying, this is my voice and I'm unafraid to share it. And now there are platforms where they can be heard, not just in the immediate vicinity, but on a global stage.

You were talking about music festivals earlier, and you've mentioned many interviews before. Glastonbury, Burning Man, these really inspired you. I wonder what it is about those events that sparked your imagination.

Fabien Riggall: I think Glastonbury, I went from 15 and I think I've gone nearly every year.

Ling Yah: That's a lot of times.

Fabien Riggall: Yeah, it's a lot of times. I actually went last year and it's got so big now. I mean, I love it to pieces still. There's nothing like it, but it was so busy. I think Glastonbury in particular, going there as a 15 year old. What was so interesting was the culture around the music, the counterculture, the political side, the environmental side with Greenpeace having a big part of it.

But also, yeah, the drug side of it was this sort of sense of discovery and excitement and a young person.

I think it's being safe, but was just, it opened my eyes to not just the drugs. But the sorts of culture, if you really think about it, same with Burning Man. It's this idea like everything is created and anything can be changed.

And everything is made up in the same way a writer writes a story. Like it's just a story. And the story has actors and those actors can be changed.

So I think there was this moment of realization during that time at Glastonbury, but also going to the cinema and being influenced or going to a festival was that these are just stories and they can be made up. They can be changed at any time.

And I think secret cinema or other projects that I do, it's just a belief system. It's like, here is an idea, here's a story, would you believe it? Yes.

Well, therefore it becomes real. It's an audience of one. Well two between yourself.

The idea behind initially Secret Cinema was this secrecy of not knowing where the venue was or not knowing what the location was. That was all built from the mystery that I would feel at raves or Glastonbury or just the kind of mystery you feel in life when you don't want it to be predictable.

You want it to be different, and yet everything's trying to make it predictable and boxed in.

Ling Yah: You mentioned Secret Cinema. It didn't just evolve from day one. It started from Future Shorts, which is a network of mini film festivals. And I wonder at what point did you go from attending things like Glastonbury and Burning Men to going, I want to run my own festivals and actually doing it.

What's that progression like?

Fabien Riggall: I went to film school, went to a few universities, didn't work out and I was incredibly lucky to be able to have the opportunity to go to New York Film Academy and go to a film school.

And there my trajectory was to become a producer. My focus was I'm gonna try and be a producer. And then I think that there was this moment when I worked on different films as an assistant and I was climbing my way up this ladder. This impossible ladder.

I wasn't making enough money so I got a job in telephone sales. My job was to sell advertising to editorial space on a news channel.

Ling Yah: That sounds soul destroying.

Fabien Riggall: Yeah, it was pretty soul destroying. The main premise was it was Euro News, which is a channel, and you had to sell editorial to CEOs by saying that you're doing an interview with them to highlight their amazing career and by the way, it's gonna cost 20,000.

But in order to get through to the CEOs, you had to research the stories of those two CEOs just like you do. And then we had to basically pretend that we were this big editorial organization. So I would have multiple assistants.

I would have two or three assistants that were all myself. I would be like pretending to be my own assistant. you know, It was just a hustle. But what happened was that before that point, friends would ask me, what are you doing in your life? What do you wanna do? I'd be like, I'm trying to be a producer.

And this was a really important point was that there was a certain confidence. When I did this television show job, I would have to play a role and basically I would say, yeah, I'm the head editor of this channel, whatever.

I would have to then pretend to be different people. At a certain point, I started working on producing a short film. And the short film I would put every call to try and do a sell in for my telephone sales job, but then the other call would be producing this short film.

When I ring up, my confidence was just a different thing, was just like, there'd be like, yeah, I'm a producer. I've got an extraordinary film project. Can't tell you too much. A lot of people are interested about it. And it was just a hustle. But what it made me do in my own mind was, I'm not trying to be a producer. I am a producer.

And just that statement, which I would recommend to anyone, whatever they want to do, is that it's a total hustle. It's a myth. The whole thing is based on what you say you are, you become. What you want to create, you create. It's just whatever you want it to be.

And so that got me into a position where I became a producer. I produced a film and then produced a series of shorts. And that led on to a friend of mine letting me know that she was starting a club. An underground club, music, film, art, and she wanted someone to come and program it.

So my brother and I thought we had put on a night of short films. We were seeing a lot of amazing short films.

We were producing them, making them, and realizing that there wasn't really a big outlet for them. And so that's how Future Shorts came about. It started in 2003 in a basement club called Gimlit in Shepherd's Bush in London.

We had a hundred people at the first screening. And then we'd have DJs after the screening. And this idea of social cinema or this idea of a night where you combine different mediums, that started.

And so we'd put this films onto a dvd and then we would send the DVD to other partners in different cities who would then find their own venue and put on the night.

And then from like five in the uk, we suddenly went to about 80 in a few years of people running these nights. The idea was that, say for example, if you were a future shorts partner, you would find local films and then we would then find local films in lots of different countries and then put them together as a kind of mix tape.

That idea grew. But the, the main premise was it to stage these events in places around the world. And that's kind of how it all started.

Ling Yah: And this time when you were starting future shorts was 2003, where the internet was kind of just starting as well.

So I imagine everything was just physical. It was very different from the world we are in.

Fabien Riggall: Yeah. I think the internet was starting 2003, but then as it was beginning, therefore the whole digital culture was beginning to weigh in.

And so by the time that we launched Secret Cinema in 2007, that internet culture, like the rise of digital culture was growing.

Ling Yah: When you started Secret cinema, did you think from the get go, I'm also gonna leverage on the internet?

Fabien Riggall: I didn't really think of it like that, but I think, yeah, we definitely used the internet. And at that time there was MySpace.

Facebook was just coming in. YouTube to a certain extent. Yeah, so definitely when Facebook started, it definitely helped us harmonize, gather, galvanize the community.

And that point, the algorithm was much kinder, you know, like you could actually post something and it would reach someone without having to pay them money.

So yeah, we used the Future Shorts mailing list. We built up this kind of decent community with future shorts.

The premise behind Secret Cinema initially was more of a guerilla screening where we would break into abandoned spaces with a projector and then like text everyone or have a number that they call. A bit like the raves.

It started like that and I realized that there was a much bigger opportunity with Secret Cinema.

I realized that there was something beyond it being just a kind of more of a guerilla screening, but actually that there was a form there where you combine theater and cinema and the idea of a rave and sort of blur it together.

Ling Yah: Wasn't the first one you did, you taking over a tunnel and creating this secret skate park and it was like five pounds per ticket and you sold out within an hour?

What was it like running that first event?

Fabien Riggall: Yeah, I think what was interesting was it started off with that concept of taking over abandoned spaces and putting on screenings.

But yeah, what happened was that the tagline was, tell no one. So it was secret cinema, tell no one.

And the premise was that we wouldn't reveal the location or the film and we would send an email out and give you a character.

You became part of the film, the story. The first film we did was Gus Van Sans paranoid part, which is set in a community of skaters where one of the skaters has been investigated for a murder.

And we found these old tunnels, which are underneath London Bridge and turned the tunnels into a skate. An illegal skate place where the audience became part of that skating community who were all under investigation for murders.

They arrived at this sort of like tunnel. which was like, There was a bridge with trains going past, with a security guard shining a torch in their faces.

And then they were brought into this space and, you know, at that time it was, I don't know, it was like five pounds a ticket. Our budget was tiny, but we got some skate, some ramps and some various professional skaters who came to be the skaters.

But you know, the sound was terrible because it was based in these tunnels and we didn't have the best sound system and everything, so the sound sort of reverberated in all the tunnels, but it was quite atmospheric. I'll send you a picture of it.

That was the first one, but at that first one, there was this moment where we were sending out the email, and I think I miswrote something on the email. Initially, we weren't gonna reveal the location.

And then I think I wrote something like, we will not reveal the location or the film. And I think I made a typo mistake. And then I looked at it and I was like, yeah, we're not gonna reveal the film either. And at that point it was like, well, how would you sell 400 tickets without revealing anything?

And then it was this idea around mystery was like, actually, what you don't know is what you really fear you'll miss out. You really care about things when they're secret, you know? And it's a lovely thing when someone does a surprise for you, it's a beautiful thing. They really think about it.

Like, how would we create a surprise party for this person? Or how would you make a mixed tape for someone that you love where you really think about what they're gonna feel.

So therefore, I think that was a big part of it. So I made them mistake. We sent the email and it just captured people's imagination.

As I said, it was the rising times of the internet. It sold out immediately. It was well received. And at the first secret cinema went up at the end of the screening and I made a speech out of character that said, thank you for coming. The future shorts was always there would be a host, someone would welcome everyone.

And for the first three secret cinemas, I'd come up and go, thank you so much for coming. But then it's sort of like, no, why are we doing that? It's breaking character and then it's like, no, we've gotta make it real.

It's gotta feel like you're inside a film.

Ling Yah: I wonder, what does it take to run something like this?

Who are the people you manage to gather? Because it's not a one man show, you definitely need the right people who are also really passionate about this, with the right attitude, like the right vision. How do you find these people?

Fabien Riggall: Yeah. Future shorts, it just grew from my brother and I. and My brother stepped back to be a filmmaker.

Other folks that started finding out about it and just getting involved on a part-time basis.

But It just grew, I think it was just future shorts.

We started doing shows and events. There was something called Future Cinema as well, which I won't go into, but that was from 2005 to 2007, which was taking the concept of future shorts, but taking movies like Nora Metropolis and these sort of things.

So it just grew. So I had a team. I had a team of people that we built, and it was just people who were looking to do something different.

But what was interesting is that as secret cinema grew, we had to build a sort of hybrid team of people that were from the theater world, the cinema world, and the event world.

Yeah, it was a hybrid thing to be able to do what we wanted to do. Because the thing about Secret cinema was and why it's hard to replicate is that it was a deeply emotional, personal, chaotic, confusing.

You know, we just make mistakes all the time because it was done from the heart and it was done out of passion and it was quite reactive at times. I think both myself and the team would just be like, oh, we just had an idea. Let's just do it. You know, there were no rules. So sometimes we'd make mistakes.

Like the email wouldn't go. Or we did the wrong thing with the email. So we send the email to newsletter and they didn't receive it. And then people on social media were like, oh, it's so clever what they're doing. They didn't send the email. That's so clever.

And then we were like, holy shit, they really like that. For example, when we did One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, We did a partnership with The Guardian. They gave us 200 grand worth of media value.

And instead of just advertising, we created a fake organization called The New Wellbeing Foundation. The idea was that we were gonna build this kind of like new treatment, which was based in electric shock therapy, which is based on this new treatment for those with mental illnesses in the early sixties or whatever it was that came in.

So we created this whole fake organization and then we sent a letter to the audience and we told them to fill in this application for this new Wellbeing Foundation. That was advertised in the newspapers.

So people didn't know whether it was real or not. But then we psychoanalyzed them, had a psychiatric test, took all of their information, understood exactly the relationship with their parents and all these different things, had all this data on them.

And then,

Ling Yah: It would never fly. It would never fly today with the GDPR.

Fabien Riggall: Yeah. You say it never flies, but we are living in it. Like those companies know more about us than we do. And what we would do is do it purely to sort of hopefully enrich their experience et cetera.

But what was interesting is that we, for example, in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, we decided that people have been misbehaving in the same way that the writer Ken Kesey, I think his name is yeah. On the film, is that, they've been misbehaving and so therefore we were gonna stop any form of communication with them which is madness.

We shut down our website, all our Facebook, and we said you've been misbehaving, therefore there's gonna be a 48 hour blackout. And then we just shut everything .

The point I make is that there were sort of no rules and we could do everything that we wished.

I think the premise of it was exactly what I'm doing now, is to give power back to people in terms of culture and entertainment and take them off the conveyor belt of predictability and then put them into a position where they have agency. I hate that expression.

They have control of their own thing and that's how it kind of started. And I was thinking like, if you could build a studio the size of Disney out of a secret then you can change the world.

But the point I'm making is that so much of the world is predictable. So the idea of people buying a ticket, of which 30, 40,000 would, without knowing what they were gonna experience, where they were going, and give huge trust to us as an organization, then I felt a responsibility to push things in new directions.

Ling Yah: I love what you're doing. The fact that it's basically turning what we accept as the norm and saying, no, you know what, let's do it differently.

And the fact that it was mysterious, it's unknown, that's something that I really loved about Secret Cinema, but I'm just trying to put myself in your shoe.

I would love to run an event like that, but if I had a big budget, I would also be really worried as to whether the audience would even care about this. They would actually even buy a ticket. Would I be able to make anything out of it and go back to my investors and say you know, your money is safe with me.

So how did you manage the risk of it just falling flat on your face and also just pushing the boundaries of what could be?

Fabien Riggall: That's a very good point. I think the way that I approached it and somehow we survived was this idea that essentially when future short started, a hundred people would come. They'd pay five pounds a ticket that would go into the budget.

Then we would do another thing.

Any money that was left over, we would reinvest in the next month, do something more. Bring a dj, whatever.

So it just grew from that. So essentially the investors were the audience. And more than ever, now the investors can be the audience, right? You look at this like sort of extraordinary world of like crypto and all the sort of web three and all this stuff.

There's a real opportunity to decentralize a system and not have to go to normal traditional investors and actually build things that people perhaps might not normally, because essentially you can crowdfund everything or just build a hun a thousand NFTs.

Essentially we were crowdfunding.

The first secret cinema, 400 people came. They spent five pounds, then they spent another five pounds on drinks. And so the profit that we made from that first event went into the second event. Then we grew because there was word of mouth.

How do we do it? I think, purely just really through the word of mouth. Through having this sort of weird confidence that this was gonna work from somewhere and just doing it like club nights.

If you look at theater shows often that's how they worked. It wasn't a Ponzi scheme. That's a horrible word.

So from 2007 to 2000 and like 12, as it was growing, it was just based on the audience. Most people, they like, let's get investors, let's get some money in, let's get it all finance. Then we do the show. No, it wasn't like that.

We got the money through the audience's belief in the thing. So they were the investors and then we were doing shows without revealing anything of the product. So they were investing in a secret. What made it special is that each and every one of them created secret cinema.

Like the team behind secret cinema was one thing. They created secret cinema. But the second part of it was that the audience became participants in it. In the early stages they facilitated it. And the weirder we got, the more they loved it, you know?

Occasionally they didn't like everything we did, but most of it they were sort of down with. And even when we got it wrong, they accepted that we were pushing things in a direction that other people hadn't pushed for some time.

Ling Yah: One thing I've learned as I'm speaking to more marketers and storytellers is that what we, the general public see is very simple, but behind the scenes as a whole team who really sat down. Really thought about it and strategized. For instance, mystery was what key component of what you were doing.

What were some of those key things that you did to create mystery, cuz it's one thing to not say anything, but in order to create that sense of, Ooh. But I dunno, but I really want to know.

Fabien Riggall: When we did Shawshack redemption the premise of it was that the audience were all under suspicion of murder or a crime that they hadn't committed.

And we created 30,000 different like crimes .

Ling Yah: That's a lot .

Fabien Riggall: But the idea was that they were going to a court to be judged and tried and charged for a crime they didn't commit like Andy Dre the main character.

And that court was an old library, which we used.

The way that we would create the mystery would be that at this point weren't revealing the film and so we would just send these little announcements. Like there was a newspaper which we created, and that newspaper was written with stories embedded in it without revealing that it was Shawshank redemption. Just that it was set in a town somewhere in America and that it was connected to incarceration. But you know, they didn't know what the thing was.

I dunno, I'm trying to think what other mysterious things we would do, but, you know, we do kind of things. We did Star Wars. We would project these codes on different buildings around London, and those codes were connected to a part of the narrative that essentially following the clone wars of a new hope.

The idea was that following the clone wars, all of the rebels were hiding on earth, and we were waking them up with these calls and that they would follow all of these different projections that we were projecting on different walls. And they would end up in this kind of club.

And in that club would be where we reveal that they were now rebels and they were part of this whole Rebel X movement.

What I was always interested in was, again, I think I mentioned it earlier, that I see the world as a stage. And I see that every newspaper essentially are just story makers as we know. Some of them are more corrupt than others, but the idea is you can subvert all of that, right?

Now the ability to divert is terrifying. Misinformation and how we operate, you know, How we look at the news. How we watch the same Netflix shows.

So I think even now more than ever is the chance and the need to like subvert.

But I don't know how we did it. We wouldn't reveal anything and we would just give these clues and get people intrigued about it.

Ling Yah: Hey, STIMIES!

Interrupting this just to say this is essentially my year of yes, to meet, to explore, to see what's really out there beyond the world of law. While, of course, also doing the STIMY, which comes out every single Sunday. Now the thing is I've started to also help other people to build their personal brand.

I've spent the past three years essentially digging deep to the lives of Olympians, C-Suite executives, four Star Generals, and now YouTuber and Viral TikTok is as well. And what I've learned is that LinkedIn is an amazing platform to allow me to tell these stories, to allow other people to share their stories, what they're passionate about.

What they're trying to do to change the people, to change the community, the world around them. So if you are interested in also learning how to build a LinkedIn personal brand, do, reach out cuz that's what I'm helping people do right now.

Just drop me an email at, [email protected] and let's get started.

And if you're not sure what that looks like, just head over to my profile, look me up Ling Yah. And you'll see what I'm doing so far, snippets past guests and also what it takes to be a great storyteller.

Now let's get back to this episode with Fabien Riggall.

It sounds like you've built trust because it's not like you came out of nowhere. You've been doing it for quite a few years. It's been done really well and it sounds as though the main audience, the main driver is really just your newsletter and the emails you sent.

Fabien Riggall: Yeah, I think the email was the main part of it. You know, The one thing is that there would never be traders cuz it was secret initially, right.

We were doing secret shows and then we were also doing non-secret shows like Lost Boys, Top Gun, quite big films. Then Star Wars, Back to the Future.

These were like big kind of shows. And then we were doing more provocative ones, like One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest, Battle of Algiers, Shawshank Redemption, the Third Man. It was always this balance. I knew that I had to sort of sell a lot of tickets to be able to continue to do the more provocative ones.

We would combine these different types , in order to be able to create this word of mouth and the secrecy.

You talked about trust. When we did Shawshank Redemption, you know, this was quite a severe film. Yes. It's a classic film. It actually wasn't a mainstream film when it came out, but it's a provocative film and to me, what interests me about all these films is that they have this sort of social aspect of them that are connected to a bigger theme, which is a message around incarceration, mental health, the environment.

Blade Runner was about the environment. Redemption was about incarceration and Rehabilitation what works, what doesn't work. Prison system, et cetera.

I think that with Shawshank for example, the premise was this was an all male prison. The audience were being charged with a crime.

They were becoming participants. They were being charged with a crime, going to a courthouse, tried put in, a blacked out bus, taken to an old school that we invited into a prison. Stripped.

Put into their underwear, given prison uniform, had all of their possessions taken away and then put into a cell.

And that's women and men being stripped. That sounds kind of crazy, but the trust was, we believe in this new form and we want to take part because not only is it entertainment, but also it's actually looking deeper at the, the message behind it.

To me that's the most interesting thing about secret cinema is this idea of actually through art, I changed my mind about prison. Through art I changed my idea around mental health or through music, whatever it may be.

So yeah, the trust, the word of mouth, that's how it was really important. And I think, now, people are terrified, I think, of artists of being canceled, of doing something that is gonna provoke one side versus another side.

I think we need to liberate art because I think it feels like a lot of it has been pushed under. Everyone's fearing to doing something that's quite provocative. Art should provoke you to think and feel something.

It's not just entertainment or content, you know?

Ling Yah: Was there a limit to that provocation of thinking maybe this is too far, maybe the audience isn't ready for it. Did you ever have that?

Fabien Riggall: Yeah, I think so. I think that there's this sort of sense that we've definitely pushed the boat on certain things.

It was quite unsettling on One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest when suddenly you have no freedom and you're put in a ward and you've been told that you're mad. I think is quite provocative.

And We worked with a lot of artists that were suffering from different mental health issues. From schizophrenia to bipolar, and we wanted to explore this because from then onwards, that film, which was shot in the eighties or not eighties, seventies, I think was breaking the taboo around mental health.

But there were times when people were in this dark corridor with Simon and Garfunkel, the sound of silence with smoke like bellowing out and it said hello, darkness, my old friend.

We were trying to make it serious and it was serious. And we worked with doctors and professional people in the psychiatry world to explore these themes that the film asked.

Yeah, there were times when people, it was too much. Shawshank Redemption, I think every night we had a few people who we had to remind that it wasn't real and take them into another room and give them a cup of tea. We'd let them go because they were like, this is insane.

Ling Yah: What about for yourself?

Did you ever feel unsettled by something that you were doing?

Fabien Riggall: Yeah, I think that if I didn't feel unsettled, I'd feel that something was wrong. I just wanted to provoke.

I pushed very hard, this idea of a dream I had as a child. I guess that was my skill. Maybe my weakness as well.

Ling Yah: Were there particular ways in which you could encourage people and push the boundaries?

Cuz I imagine for lots of people, it's very hard to motivate people under you to say, no, no, no, this is the limit. But you can go further. Think further.

Fabien Riggall: I was good at certain elements of getting people to think further. For example, when we'd go around a building, I would find the building, secure the building and go, okay, this is gonna be a prison. It's gonna be Shawshank redemption.

Or this old carpet warehouse is gonna be more marked the be park for Moulin Rouge. Or this old factory is gonna become Star Wars.

Often people thought I was mad. Maybe I am a little, but the point is the madness was a strategy, if you know what I mean.

If you're confident and mad, or they think you're mad, or the perception is, okay, we're gonna transform this building into an apocalypse, a zombie apocalypse that is occurring due to the cuts that the health minister has made. And the whole building is gonna be filled with zombies, and we're gonna turn off all the lights and people are gonna have to run for their lives.

I built a team who was skilled and confident and they made it happen. So without them believing it, it wouldn't have happened and the audience wouldn't have believed it.

It was just all belief. It's like a child believing a story that their parent is telling them. It's a belief system.

Ling Yah: I was wondering, because you have clearly spoken to so many different people, it's not a production that takes one month or two months to produce.

When you speak to different people or you run certain productions, you might have raised new ideas or new ways of thinking and you have transformed the way that you live your life for instance. Were there moments like that?

Fabien Riggall: Yeah, from the age of 27 where I set up secret cinema to probably now, it's had a big part of how it changes my identity.

And I think this is something you've gotta be careful of because you know, there's a certain point where you really have to protect yourself and the people around you.

You know, when you get this idea and you grow it, and then you obsess with it, you have to have these two worlds, these two lives.

I think that was part of the success of it, was that there was no difference, you know?

And I would have debates with various folks about the money people that, well, obviously their vision was to sell it. And to grow it enough so that it could be sold and, thank God they have that vision. Because I think as an artist or as an entrepreneur, you sometimes get so wrapped up in it that you just want it to be perfect and, you know, you're only focused on that.

Ling Yah: When you do require assistance from other people outside, how do you balance needing people to come in? They obviously want to have a voice, but also being able to say, I also have my creative vision and my voice. How do you find that balance?

How do you do it?

Fabien Riggall: Yeah, I mean, I think they're two very different things.

There was this sort of patronage of artists in which they would have funds to create art. And the transaction was less important. It was just to create the work.

But I think in terms of investment I got help from early stages.

And that money came with a price but it also enabled us to grow. So, it's an alchemy of all these different things. However, I do believe that maybe if I'd spent a bit more time making sure that the financial side of it was all set up, then I wouldn't have been in a position in which I would've had to like, seek a major amount of investment, which meant that I, I would step back.

So it's a difficult one. But I don't regret any of it. And I also think that the partners that came in did what they said they were gonna do.

The company was sold.

We have disagreements and different ways of thinking about it. And I really believe in a world in which we're not dependent on companies and we don't become, like, subservient to other organizations.

The idea was to build a secret world. To build a studio and to grow that into something that would give power back to storytellers rather than storytellers becoming slaves.

A hard way of looking at it.

With my new venture and bringing in different artists and creative directors and trying to take a step back from the beginning because that was a thing about secret cinema. But having said that, I very much did work with some of the best creative minds, and they now are the creative directors of secret cinema.

And so, I was training people to come and essentially, put their vision and their spin on it .

And everyone that's there now on the creative team, most of them came from the time when we were doing things up until running Secret Cinema until 2017, where I stepped back.

I sometimes just wish that when you come up with an idea, if you're a writer, the battles with yourself you know? and you just need to keep the discipline and the story and focus.

You don't have to have 200 relationships. Each production felt like a battle because there was always people that would say, no, it's not possible. The thing I would say, yes, it's possible.

And I think going forward, what I'm looking to do, is to empower and step back and find other ways of achieving things without the battle.

There's always gonna be a bit of a battle to allow people to have autonomy on what they're doing. You know, I was very controlling, but in my defense, I was protecting the thing. The special thing that we were all building,

Ling Yah: What were some of the biggest battles you waged and won?

Fabien Riggall: The insane battle that we had, which was nearly the end of secret cinema, was for anyone doing shows and events on a large scale be very careful with the deals that you strike with the people who own the space, the land, et cetera.

But yeah, It was that we'd come out, I think of doing Miller's Crossing, which was the Coen Brothers movie and we did that in an old town hall in North London.

It's a really beautiful film if anyone hasn't seen it set in the kind of gangster world, but in a kind of very Coen brothers style.

It was great success.

And I think we just done Grand Budapest Hotel and we were sort of riding high and we managed to get the rights of Back to the Future.

A wonderful chap at Universal Studios, I think his name was Neils Swinks, he was a great guy. Back to the future was a complicated rights thing. But we managed to get the rights and then we were looking for a space to build the town of Hill Valley.

We wanted to build the town and create a real living, breathing version of this 1955 Hill Valley. We went to loads of places and we found this space, just next to where the Olympics was in Stratford. Next to the shopping center.

We leased the space and the space was like just a bit of tarmac.

When we built the town, we would go to the authorities and planning and fire, police, et cetera.

We told 'em we were building the town of Hill Valley and there were gonna be cars driving around and there was gonna be three and a half thousand to 4,000 people attending each night, and it was gonna be a real town.

And they were like, what? You're building a town? That's insane and there's cars.

And he said, yeah, and some of them are gonna drive at 88 miles an hour.

I think I did an interview and I said, yeah, we're gonna build a town and the audience essentially are gonna become residents of Hill Valley in 1955.

They're gonna have their own address, they're gonna have a job. And we did, we built a town with like, a hundred businesses, town Hall Police Fire, it was like a real thing.

It was like Sin City, you know? It was like now people build towns all the time, but they don't do it in three months and they don't do it when the developer owns the license.

It was a fight because it was the perfect storm. So you had the health and safety team from the Olympics. You had a massive developer who kindly had agreed to rent us the space, but they had the relationship with all of the authorities, so they got very nervous.

The health and safety from the Olympics, you know, their last job was the Olympics. So they wanted to let folks know that they were good at what they did.

It was just the perfect storm of us also just wanting to build something so huge. Yeah, that was the greatest battle and I think we nearly lost it.

There was this lovely lady actually called Fiona, I forget her surname from Green Man Festival who literally stepped in when we were a group, I think there were about 300 people working on it. The press had gone in and basically what had happened is that we weren't able to open because the authorities wouldn't let us.

So that we had to turn away three and a half thousand people on the first day. Cause I refused to not open the site. Cause I was thinking, we're just gonna persuade them. And we never did. So three and a half thousand people traveled from all over the world in 1955 costumes arriving at this destination.

At that time I was still furiously trying to fight to open it. So there were actually some of my production team that were at the station. And people were so sad and upset cause people had come from everywhere. We should have canceled it earlier. So that was a very big battle.

What happened was that we had some help. This lady Fiona came in and we just basically went to war and we improved all the things that they were worried about. We changed our security team, whatever. Anyway, that was the biggest battle.

And then it opened and then 80,000 people attended. And it was one of our most loved productions and I think still is today. What was interesting is the story of Back to the Future is about ambition. It's about a kid, who's living in a small town in America, he says like, if you wanna achieve it, you can create anything.

I can't remember what the expression was. And it really was that. It was gonna be either the birth of the next chapter of secret cinema or the death of secret cinema. Luckily we won and it continued.

And then rather than just go small, we got the rights of Star Wars the next year and just went completely crazy and decided to build the biggest experience we could.

Ling Yah: The entire experience of running secret cinema sounds all consuming. I wonder at what point did you think I'm ready to step away?

Because I imagine it was very much your identity, it was your baby, and how do you step away from something that everyone is associating with you?

Fabien Riggall: Yeah, it's my baby, but it's a lot of people's baby, I guess.

It had a lot of adoptive parents and initially those parents were sweet and kind.

Ling Yah: As they all are.

Fabien Riggall: Yeah, that's a very good question. I think it was in 2000 and you know, when we did Star Wars that year, we took over this building. We did three productions. Dr. Strange love.

I think the premise buying Secret Cinema, there was this strategy, which perhaps I wasn't even aware of, that I was making up with my team as we went along, which was to build the next chapter of entertainment and to create something that perhaps would alter the system in a way that would allow a new fresh wave of ideas.

I think it did that. I think the immersive industry now is huge. And I think that alongside other organizations, we were the pioneers of this new form.

There was this moment when we did Star Wars, a hundred thousand people came.

It was an incredibly difficult year. The building that we took over was an old factory that we had to transform into a venue and it was very challenging. What excited me was the kind of subversive elements of everything.

We did Dr. Strange Love as a kind of warning when Trump was campaigning And what's weird is Dr. Strange have sort of come to life in a way, if you can imagine it.

It's kind of Biden and Putin, but then it was sort of Trump and Putin. And then when we did Moon Rouge, it was this idea of anti-Muslim rhetoric and this horrific kind of narrative of America first, et cetera, that we wanted to do Moulin Rouge, which was to say that, you know, during the early 20th century in France, there was this huge creative renaissance.

From that time we'd explored other forms. We created a secret restaurant with St. John's for the third man where we would create an immersive dining experience.

We did a secret nightclub with Star Wars where we created a separate event where we took over a club and turned it into the canteen bar.

And we'd done a hotel with Shawshack Redemption, where people could buy a ticket to basically be in prison for the whole night.

And secret music where this was like the beginnings of an idea of which we did with Radiohead. Taking the soundtrack of an album and turning it into a building. And then we did this with Laura Marling.

Anyway, the point I'm making in a round about long-winded manner is that we were always exploring new ideas and new forms and new formats, and there was a point where all I was doing was firefighting the problems of having this huge scale operation.

We were doing a hundred thousand people a year. Actually on that year was 140,000 people came in 2016.

We could have carried on in the same way. But I felt a responsibility to Secret Cinema, to the team, to the audience to make sure that it doesn't die.

But on a personal level, I was no longer able to move as fast as we were before because the thing was so big and also hadn't put in the right structures and strengthening the foundations of the organization. It was always run in a chaotic fashion.

But that chaos was very strategic and maybe even selling a majority of the company was strategic.

Essentially I was always wanting to explore the core of why we did it in the first place. And I think when you start something and it just grows into different forms and you lose track of why you started it or what the original intent and the vision was.

Ling Yah: Do you feel like the original intent altered along the way and when you sold it, do you feel like you achieved everything you wanted to achieve with secret cinema?

Fabien Riggall: Not at all. No.

But essentially I am deeply proud of where it's gone and where it's got to.

Since I stepped back 2000, I was the chief creative officer for a few years and Matt Bennett who came on initially to work on the music side, took over as creative director. The productions have just grown and the last show that I directed was Blade Runner.

Since then, there's been some wonderful productions. The thing that I was nervous about was the main premise behind Secret cinema was not revealing anything, number one.

Number two was this idea of participation. Going back to the situation is that this is about participation and it's not a spectacle.

That this is about creating something together where there is no difference between the audience and the performance. And there's a blur that allows people to be free. And it allows people to not feel that they need to be entertained, but they're also entertaining each other by playing characters. And no one knows who's an actor and who's an audience member.

And that was so important. And also in the way that actors do amazing job, extraordinarily complicated. The craft, to allow audiences to come right close to your nose, you know, and to actually have to interact.

It's exhausting. I give a lot of Secret Cinema to the actors in terms of that success.

But what I used to on Blade Runner was working with my creative directors, my team Lucy Ridley, Matt Bennett, Tom Maller, was to not lose that ability to blur the world and to not make it about entertainment.

But it's about allowing it to breathe and to be this kind of world that has new rules.

Everything is in character. But I believe that there could have been another way of how you can allow that to continue and scale it globally, right? But there's always a point with a product where you've gone from building this prototype to then needing to scale it and grow it.

And how do you scale it and grow it without losing the reason why you started it in the first place. So yeah, there's an element of that. However, our new partners who bought the company are a ticketing company. They reinvented ticketing. They're very passionate, brilliant business people. There's a great team working on it.

Max Alexander the CEO, is a force of nature. We have different ideas on things as, as people do.

But without having that force, I think it wouldn't have survived the pandemic. I think it's a miracle it survived the pandemic because the pandemic meant that we, for two and a half years had to shut our doors.

It's always the founder's dilemma.

You want your baby to grow up, but you want it to go down the path that you'd intended it to. But sometimes it doesn't, it gets corrupted. But what I will say is that in this occasion, I went to the Guardians of the Galaxy.

I went to Dirty Dancing this summer. Both productions were flawless. Both productions had the same magic that I had intended.

You know, secret cinema started as a secret. It was a dark forest with just tell no one on it. That was the flyer. Not to forget the core of where we came from, and I think that's a lesson that the money people sometimes forget.

However, I think that our investors know this, and I think in a way they have, which I understand is that they're going to look at how they can bring back that sense of mystery as well as scale it around the world. And that's the balance that we need to make work.

Ling Yah: Fabien, you're now working on Lost. What is lost?

What can you tell us about it?

Fabien Riggall: Lost is an extension really of the vision that I've had. That I feel society has had.

So lost came out of this premise that we are all lost. We all are constantly trying to find ourselves through this sort of predictable storytelling of social media, of society. We've forgotten the ability to lose ourselves.

Maybe we've also forgotten the ability to feel. To really feel. To spend time lost. To go for a walk without your phone. To go and see a movie without looking at the review.

Lost is also this idea of reimagining formats in the same secret cinema, reinvented cinema.

The idea of what could happen with music, with art, with theater, with fashion. How can we reinvent why we go out of the house? Why do we need to leave our phone? What do we care about when it comes to culture and entertainment?

So one side, it's the breakdown of mediums, and I call it like breaking the walls between medium.

So It doesn't matter whether you're a filmmaker or you're a theater maker, you are a writer.

You break the walls between the art gallery, the cinema, the museum, the theater, the concert hall. There's just one. So an exhibition is a concert, is a club, is an art installation.

There is no difference.

If you look at artists that are already creating universes, like Kanye West, as an artist, he is breaking form and realizing that it isn't one story. In fashion can be the same in music.

So lost is really just about building a community that want to lose themselves, that want to experience art in new ways. And it's a creative studio to essentially build new formats.

So we're exploring music and looking at the future of how the live experience and the recorded music and what is the future product of music and how can we break away from this kind of sense that music comes from Spotify or it comes from Amazon Prime or Amazon Music.

The artists are forced, literally like slaves to produce TikTok videos in order to capture the algorithm. It's not to suggest that those companies don't have great awareness for artists. They do, but they are capitalizing in a way that I don't think is good for the artist in the long run.

I'll give you an example where something is good. So you've got an artist like Kendra Lamar, who's to me, one of the most exciting artists worldwide. He does this extraordinary tour, this amazing concert.

And Amazon did a deal with him to shoot a film of that tour and allowed people who were on Amazon to experience that tour for free.

But it's not really for free. You have to pay 70 pounds a year, et cetera. I don't have a really criticism of that because in a way that's democratizing his concert to allow other people to experience it around the world.

What I have an issue with is this idea that artists become content providers for platforms. It should be the other way round. Like the platform should be a place in which the artist may choose to use, in which to expose his craft without any need for giving anything up, you know?

So yeah, we're exploring all of that. Those organizations, there's a lot of what they do, which is amazing. They distributes amazing stories around the world. Like Netflix has created a huge culture around TV series from different countries.

But I will say that I believe that artists are not happy. Audiences are not happy. And there's a lot of empty buildings. There's a lot of empty shopping mall. So I think there's an opportunity to create new forms, to take over spaces to rethink the purpose of space.

That's what we're exploring of lost. And a big part of it also is just our addiction to our phones. How can we lose ourselves out of that.

Not feel that, you know, You have to tell everyone everything.

Spend time in yourself.

So yeah, that's lost

Ling Yah: For those listening who believe in the vision of Lost, say they are an audience or even an artist, how can they actually get involved?

Fabien Riggall: They have to go into a forest. They have to walk for maybe 20 miles minimum. They have to find a small cave and we'll have a little - like, no.

How do they get involved?

The way that lost world operate is that we've got a website, lost.org. On that website you can register. There's like, you'll get a feeling for the whole movement, the concept, the idea. If you feel the same things that we do, then you are lost. You're part of it.

Ling Yah: I'm still waiting to be accepted.

Fabien Riggall: Yeah. Well you're going through a major, uh, we're doing a lot of checks on you. No, I'm kidding. But yeah, no, I mean, it's like, for example, if you wanna become lost and you're from Malaysia and you're based there and you are working with local artists and you're interested in this community.

The idea is building this community around the world of people who feel this way. Like, going to interesting places to experience art in new ways, and it's lost as a collective. It's about building that.

Yeah. So they just need to go to lost.org or social media. The idea is to build our social media channels so eventually we can migrate everyone out of them one day.

Ling Yah: That seems almost counterproductive to build a social media presence, but shift them out of it.

How does that work?

Fabien Riggall: Originally lost was about building something that was analog, that would give people respite and rest from the constant screens that they have to face every day of their lives. But really the reality is you can't build a movement.

We're not building a movement. We have an idea. And I feel that many people have the same idea. I think people feel a certain disenchantment with life.

People are online and people are on social media and there's amazing things about it. It gathers people and it creates revolutions. It has extraordinary potential if you use it in the right way and you don't get used by it.

If you're like stuck in a looped existence where for hours you're just looking at Instagram stories. Hours and hours and hours, and you're like, whoa, where did my life go?

That's when you go to Lost.Org.

Ling Yah: To stop the Doom scroll .

Fabien Riggall: Yeah.

So the idea eventually is I believe there should be a new social network. I'm not sure Elon Musk is the guy, but I think what's interesting right now is everything is imploding, right?

You've got thousands of streaming companies. And you've got this war between Apple and Epic games, and Elon Musk is getting into it. And then there's this whole breakdown of politics. I mean, it's an exciting, terrifying time. So the premise is, of course, we should use these tools to build community.

But the entire presence or concept behind lost is to lose oneself and enter the physical world and to remind ourselves of that world, of emotion, of sensuality, of physicality.

Not just screen, screen, screen, zoom all day, Instagram, Netflix, all night. Like just move out. But we're definitely gonna use the shit out of it because we have to communicate with the humans. And that's where they are.

Ling Yah: Just before I start raising questions from the audience, I have one final question, which is on web three, which is very fascinating because it's all about decentralization. It's all about the things you care about, giving power back to the creators, they earn their own royalties.

Yet at the same time, web three is also all about being in front of a screen.

I mean, you enter the Metaverse. You're creating digital products. I wonder what you think of that, because it seems like they're holding two opposing thoughts that you support and also are less supportive of.

Fabien Riggall: No, I think Web three o in the right hands is incredibly powerful, and to me, during the pandemic you had Clubhouse, and then Twitter. And then there was the NFTs and then there was this whole thing around crypto.

I think the future is decentralized and that's how we're gonna build loss.

And that's the main premise behind it. I'm very interested in this idea that different partners will find different spaces and different parts of the world and those little spaces will become like this kind of village and then a town and then a city, and then like it has its own currency and then each brick is an NFT.

To me, what's interesting about all of that, and the same way of using Instagram and these things is return to physicality.

So if you can design a new world in the metaverse, but you fucking build it, that's interesting. If you're designing a fucking fake world in the metaverse in which we're gonna replace like concerts where we're just living in holograms. And that's the only thing, like I went to see the Aber experience the other day, and I must like hats off to the producers of that show. It was so good that it was terrifying.

Ling Yah: Why was it so good?

Fabien Riggall: I'll tell you why it was good. Aber being this extraordinary, like, iconic cultural moment, but the way they did it was very, very clever.

I enjoyed it and I thought I was gonna hate it. And I think that, you know, what interests me is the combination where you build a physical storytelling format, whether it's traditional theater, immersive theater, it doesn't.

The physical leads and the artist leads and then the platform, the technology follows. What's happened is that the technology and the platforms are leading and the artists are following.

So to me, the ABER experience was interesting because you can combine the two things. There's different tiers of live performance, immersive entertainment, music, art, theater, all these different things, plus the technology that allows it to grow, democratize it.

You can send experiences through the internet and people can go and experience them in physical spaces when the artist is not there. Maybe the artist can't keep traveling to all these countries cuz the environment and the cost of it is too high.

The point going back to it is that I'm really interested in how you can use Web three 0 to build a more physical world.

Ling Yah: Which seems like an apt time to move towards questions from the audience.

I have five people who have asked questions, and the first person's actually based in London and working with a web three company. So I'm just gonna play a recording for.

Hi there, my name is Chrissy Hill and I am a longtime resident of London.

I know that Secret cinema has been going on since 2008 and you guys have done a great job of offering so many different immersive experiences. I'm just wondering if you are going to incorporate virtual reality or the metaverse into any of your future offerings, cuz I think that could add a really interesting dimension to people's experiences.

And so I would love to hear your thoughts on that. And by the way, I am a general counsel for a web three tech company, so always happy to discuss.

Fabien Riggall: That's a good question. I think with Secret Cinema, very much so. I think Matt Bennett and the team there are exploring all new forms of technology.

They're using a lot of technology in the previous Guardians of the Galaxy experience to enhance the experience. They were working with a very brilliant digital screen company that did a lot of the screens. Where you can actually like create screens that fold up and move and like create circular things. Really exciting.

But in terms of the, metaverse, meta is dead in my view, but , sorry.

Ling Yah: Fair enough. Many people believe that.

Fabien Riggall: Like I went to Web Summit and I was speaking about the importance of physical experience and I did a speech and I tried to get everyone to use technology to kill the Metaverse

It was just a little silly thing, but basically the point I'm making is I don't believe in Mark Zuckerberg's Metaverse. I don't think he does either, and that's why he's just got rid of 10,000 jobs.

I do believe in the creatives and the artists that are working within that world in virtual reality and AI and all these different things.

I think that there's an extraordinary opportunity to blur these two worlds, but the physical should lead it. So yes, secret Cinema is definitely exploring that. With my new venture, we're definitely looking at Web three O. We're looking at currency, we're looking at NFTs, we're looking at digitization.

We're talking to some really great companies. One in particular I think is doing extraordinary stuff called Light Garden which is looking at that blur between physical and VR experiences.

So yeah, I think absolutely pretty interested in that world, but the physical must lead it and the narrative and the story must lead.

Ling Yah: So here's the second question.

Hi Fabian. My name is Chloe and a huge fan of Secret Cinema. My favorite one was The Stranger Things.

One, that was the first time you guys deviated from showing the whole movie because obviously you couldn't do that with so many seasons of Stranger Things.

My question for you is how did that partnership with Netflix come about?

Fabien Riggall: Speaking on behalf of Secrets and Mark, cuz as I said, I've stepped back.

But essentially, Stranger Things is always this intent. I think back in 2016 it's like creating experiences around new formats, whether it's integrating music and all these other areas.

We looked at the idea of doing a TV show and this was the rise of Netflix shows. Shows like Walking Dead, Game of Thrones and then Stranger Things was the idea of could we do an experience around that when you've got a four seasons of a show and how would you distill?

Normally we distill one film that we create a world around. The relationship began in London and we put some ideas down for what it could look like to create a Stranger Things experience.

We met with a team in London and they'd heard about secret cinema. They've work we'd done with Star Wars, et cetera. They trusted us to be able to do something with this ip.

Stranger Things is kind of like secret cinema cuz Stranger Things was literally shot by shot, honoring and tributing these films from the eighties.

It was a partnership made in heaven really. And since then we've done Briton and you know, there's lots of interesting discussions about the future.

My team going forward has always been interested in those digital worlds that live on screens. How do we bring them to life in a physical form? And at that time, we were spending so much time online watching Stranger Things.

How cool would it to be bring everyone together to share that love and be able to enter the upside down world and try not be killed.

Ling Yah: Here's the third question.

Hi, my name is the Kwokman. I'm a former CEO of a FinTech data, currently working as private wealth manager.

Question is, what inspires your choices for secret or alternative cinema locations?

Specifically, what do you look for in terms of the experience that you aim to deliver?

Fabien Riggall: Again, like putting my secret cinema hat on I think that, this was always an important one, which was the relationship between the kind of feeling of the building and the space and how it related to the story of the film.

It was very hard to sometimes. We'd have a number of films that we wanted to do, like The Shining we wanted to do for years. But it was hard to find a long drive and an estate in London. We wanted a long drive cause we wanted the audience to drive up individually in groups of four as if they're all a family

And they're all gonna go and get killed by the father. Anyway. So yeah, sometimes the location would dictate what the film was gonna be. Sometimes we changed our minds. So we found this beautiful old school and it felt very much like Shawshack redemption.

Then we found an old hospital, which we were looking for, for one Flew Over the Cookies Nest.

I think it was a mixture. And The buildings had a major part in the success of secret cinema because really everyone loves exploring empty buildings. And then when you fill them with these kind of new ideas, it seemed more interesting.

Ling Yah: And here is the fourth. It's from Nicholas.

I attended one of the early secret cinema experiences, which was Bugsy Malone, and it was hosted in East London. And I can only imagine that it would have required quite a lot of upfront costs cuz you had to pay for the venue, the actors that burst in, and then just the general food and beverage that went along with it.

What was it like to convince investors when each event held had such high costs involved? And what techniques or tips would you have for us when presenting and pitching ideas that may have similar cost profiles to our own investors?

Fabien Riggall: That's a good question. As I said from 2007, yes I had a little bit of help from friends and family that supported the early stages of secret cinema.

But essentially, we did not have any investment until 2015. So for eight years the audience was the investors.

I think in regards to those, early Bugsy Malone is one of my favorite ones, really. I love to mention it because there's a venue in East London called the Trixie, which is a former picture palace, which used to movies like King Kong back in the 1950s. The picture palace were places you'd dress up and go.

And it was a real night out to go to the movies. The principles behind secret cinema was, let's make films come to life in a different way, so that there's this sort of magical experience attached to the film and the environment. The Trixie is a lovely venue.

We went to go and see them, I think it was 2005. I can't remember when it was the actual date that we did it.

We basically said, listen, we're gonna transform your entire venue into speakeasy. The audience gonna come through the far exit, an exit that they never used before.

Then at a certain point during the night, we're gonna have gangsters break outta the screen and splurge all thousand audience delivering a thousand custard pies to everyone. Do you mind? Is that okay?

How we convinced the venues was, I think we'd had a word of mouth track record that what we did was out there. And again, using insanity, it's a great strategy.

Ling Yah: I love that. It should be a tagline.

Fabien Riggall: If people think you're mad enough to do something.