Powered by RedCircle

Listen at: Spotify | Apple Podcast | YouTube | Stitcher | RadioPublic

Welcome to Episode 46!

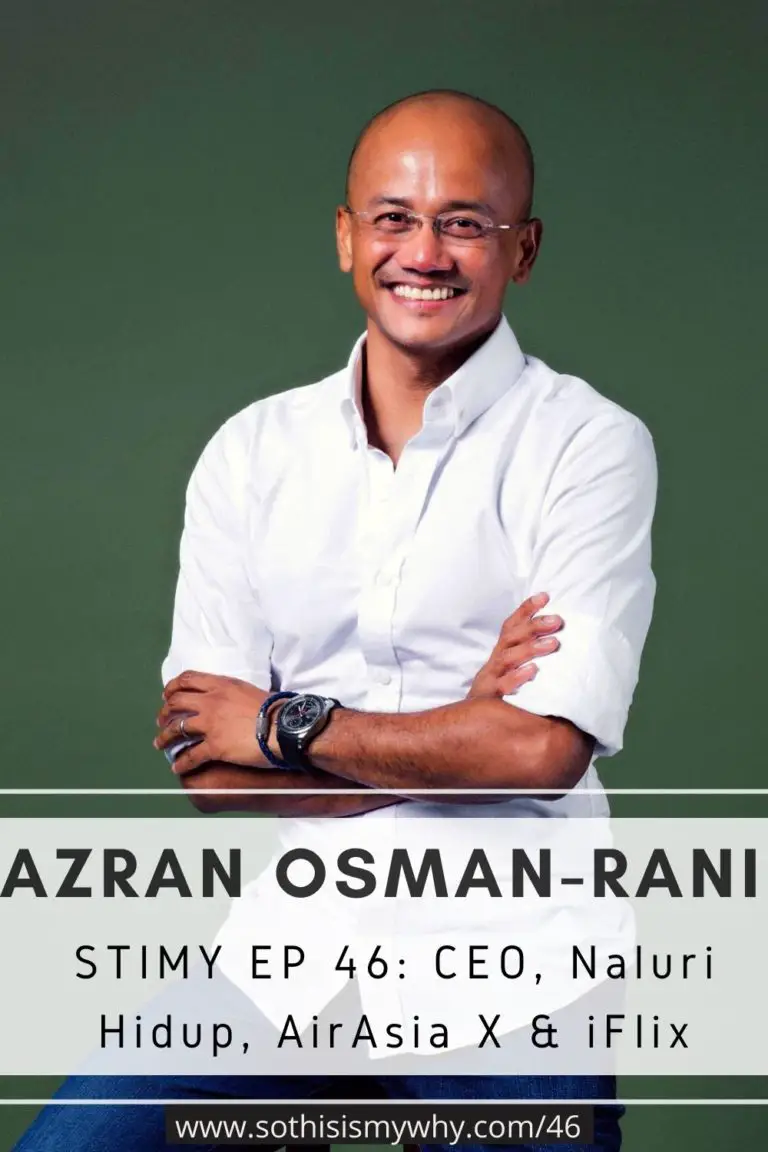

Our guest for STIMY Episode 46 is Azran Osman-Rani.

Azran Osman-Rani is one of Malaysia’s most well-known CEOs & entrepreneur and in this STIMY episode, we cover his colourful & highly impressive career that has included being:

- CEO and Co-Founder, Naluri Hidup

- CEO of iflix Malaysia. Dragon-Keeper of the Tao

- CEO, AirAsia X Berhad

- Senior Director, Business Development, Astro All Asia Networks plc

- Senior Vice President, Kuala Lumpur Stock Exchange

- Associate Partner, McKinsey & Company

- Associate, Booz Allen & Hamilton

And we cover all of that in this STIMY Episode!

PS:

Want to learn about new guests & more fun and inspirational figures/initiatives happening around the world? AND get an exclusive behind-the-scenes copy of the research notes I prepared for each STIMY interview (including things we didn’t cover in the released episode!)?

Then use the form below to sign up for STIMY’s weekly newsletter!

You don’t want to miss out!!

Who is Azran-Osman Rani?

Growing up with two professors for parents, Azran was always encouraged to speak up and speak out. This began when he was just 4 years old, where he would participate in adult conversations with his parents’ visiting guests that other professors.

- 4:23: Speak up & speak out

Stanford University in the early 1990s

Azran eventually went to Stanford University to pursue a degree in electrical engineering although he did end up doing the barest minimum amount of engineering classes required. Instead, he ended up taking lessons in history, culture, psychology, economics, ballroom dancing and even sailing!

And became highly competitive in Ultimate Frisbee.

- 6:37: Studying at Stanford University before the dot com boom

- 8:01: Ultimate frisbee

Becoming a Management Consultant

After completing his masters, Azran ended up becoming a management consultant first at Booz Allen Hamilton, then McKinsey.

- 13:45: Working at Booz Allen Hamilton

- 14:25: Bombing his client presentation & being warned he would be kicked out if he repeated his performance

- 14:25: Moving to Korea for work

- 16:18: Earning the trust of his Korean clients

- 20:28: Working to turn the Kuala Lumpur Stock Exchange from a nonprofit government linked organisation to a for-profit company (Bursa Malaysia)

Phone Call 1: To Become the Senior Director of Business Development at Astro

- 25:14: Phone call 1 that led him to Astro All Asia Networks

- 27:06: His big failure at Astro, where he had to shut down their Indonesian business & letting go of 450 staff

Phone Call 2: To Become the CEO of AirAsia X

- 28:42: Phone call 2 from Tony Fernandes that led to him becoming CEO of AirAsia X

- 30:16: AirAsia X’s value proposition

- 31:27: Building a sustainable airline business model

- 36:47: Making the pitch of a lifetime to the European export credit agency to save AirAsia X

- 39:34: Securing an upward flow of information

- 47:06: AirAsia X’s $15 million in-flight entertainment mistake

- 50:47: Staying ahead of the competition

CEO of iFlix

- 51:47: Becoming CEO of iFlix

- 54:13: Starting iFlix with a few people & laptops, but no product!

- 56:14: How iFlix gained 1 million subscribers, 6 months after its launch

CEO, Naluri Hidup

- 1:00:03: Learning about Omada Health

- 1:01:41: Launching Naluri Hidup

- 1:02:59: Why Azran bet his kids’ education, life savings etc. on Naluri Hidup

- 1:07:00: The importance of localisation

- 1:10:25: Educating the public about digital health

- 1:11:10: Why Azran is a YouTuber & active content creator

- 1:11:58: A life-changing car accident in May 2018

- 1:12:32: How Azran kept going & completed his Ironman 6 months after his brutal car accident!

- 1:15:31: Fundraising before & during COVID-19

- 1:17:05: Azran’s mirrors to deal with his confirmation bias

If you’re looking for more inspirational stories of people in the startup/VC space, check out:

- Austen Allred: Co-Founder & CEO of Lambda School – using the Income Sharing Agreement (ISA) scheme, students can attend Lambda’s coding school for FREE & pay back only when they earn over $50k/year. Graduates have gone on to work at Fortune 500 companies like Google, Facebook, IBM etc.

- Kendrick Nguyen: Co-Founder of Republic – one of the top 3 equity crowdfunding platforms in the US

- Guy Kawasaki: Chief Evangelist of Canva & Apple

- Dr. Finian Tan: Chairman of Vickers Venture Partners – former Deputy Secretary of Singapore’s Ministry of Trade & Industry who was tasked with creating Singapore’s Silicon Valley of the East & founder of a $3 billion deep tech VC firm

- Dr. Julian Tan: Head of Esports & Digital Business Initiatives at Formula 1

- Sarah Chen: co-founder of Beyond the Billion: a global consortium of over 80 VCs that have pledged over $1 billion in investment in female-founded companies

- Malek Ali: Founder of BFM 89.9 (Malaysia’s top business radio channel) & Fi Life

If you enjoyed this episode with Azran Osman-Rani, you can:

- Tag us at @AzranosmanRani & @sothisismywhy

- Tweet your thoughts & takeaways from the episode to Ling Yah here!

Leave a Review

If you enjoy listening to the podcast, we’d love for you to leave a review on iTunes / Apple Podcasts. The link works even if you aren’t on an iPhone. 😉

Send an Audio Message

I’d love to include more listener comments & thoughts into future STIMY episodes! If you have any thoughts to share, a person you’d like me to invite, or a question you’d like answered, send an audio file / voice note to [email protected]

External Links

Some of the things we talked about in this STIMY Episode can be found below:

- Azran Osman-Rani: Website, Instagram, Twitter, Facebook

- Naluri Hidup

- Subscribe to the STIMY Podcast for alerts on future episodes at Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Stitcher & RadioPublic

- Leave a review on what you thought of this episode HERE or the comment section of this post below

- Want to be a part of our exclusive private Facebook group & chat with our previous STIMY episode guests? CLICK HERE.

STIMY Ep 46: Azran Osman-Rani - CEO of Naluri Hidup (formerly CEO of iFlix & AirAsia X)

Azran Osman-Rani: And I remember flying up to London, preparing for this presentation. Taking the London underground to their office in Canary Wharf. And while I'm in the subway, you can see most people are reading newspapers, right? And the headlines of that newspaper was literally another long haul, low cost airline had just gone bankrupt.

If you remember, airlines were going bankrupt one after the other, right. I'm like, okay, so here I am going to the export credit agencies to pitch why they should support us. A fledgling long haul, low cost airline with no profit track record when just that morning, another one had gone bust. So I thought that was really ominous.

But you know, this was the last chance. There was nothing else, right. If they said no, and he had every right to say no, that's it, it would have been game over for us.

Ling Yah: Hey, everyone!

Welcome to episode 46 of the So This Is My podcast.

I'm your host and producer, Ling Yah, and today's guest is Azran Osman-Rani. Now, Azran has done many things in his career. From almost a decade in management consulting, where he helped to restructure Bursa Malaysia from a non-profit government links organization to a for-profit company, to being the CEO of a then newly established AirAsia X, the first successful low cost long haul airline carrier that went from zero to a billion us dollars in annual revenue and became the first and only public listed long haul, low cost airline.

After six years, then he went over to iFlix before launching his own digital health tech company, called Naluri Hidup, where he now is today. We cover his entire journey, including being encouraged by his parents to speak up and speak out when he was just four years old.

To how his career has been heavily influenced by phone calls, why he believes so much in Naluri Hidup and all things leadership related.

But before we begin, I just wanted to let everyone know that this podcast also has a weekly newsletter and I am going to be highlighting some of the most interesting things on people that I just don't get to do with this podcast.

And because so many people have also asked me what it's like to actually run this podcast. I'll also be including some behind the scenes, including from now on a copy of the very extensive research notes that I always make when I enter into any of these interviews. So if you sign up now, this coming Friday, you would get a copy of the research notes I used to interview Azran, which is 11 pages long, and includes some things that we didn't get to cover in this particular interview.

To sign up for the newsletter, just head over to the show notes for this episode, which is, www.sothisismywhy.com/46

Oh and by the way, I wouldn't be attaching these notes anywhere, but that particular newsletter.

Now are you ready for Azran's story?

Let's go.

You were born in 1971 at General Hospital. Then you went to Kampung Pandan, Bangsar Telawi then TTDI. But in the meanwhile, in the meanwhile, you also moved abroad.

You were in Manila when your dad did his PhD, then you were in New York when your mom did her PhD. So I imagine being so young and moving overseas must have less than kind of impact or influence on you.

Azran Osman-Rani: Well, well, okay. Well, the first time when we were in Manila, I was not even two years old, so I don't have any memory of being in Manila then.

I do remember my childhood year in New York that would have been in. 79 80. What I think it left me was being comfortable with change in new situations, because suddenly you're uprooted, you've put into a new school system, new friends that you have to form.

And then just when everything's settled down barely over a year, relocating back in Malaysia, but then again, a completely new school system and all of that. So you just have to adapt and I think that's, been useful.

Ling Yah: Even with that, you know, being able to adapt to change, your parents also gave you something of an unorthodox upbringing.

When you were four years old, they would ask you to speak up and speak out with all these professors and visiting academics. So what was that like?

Azran Osman-Rani: Okay, well, well yeah, I guess that is my childhood I was brought into the adult conversations at home and I would have to talk to my parents, friends who are of course professors themselves.

Right. Then they would ask me about my thoughts and different subjects in school or at, to show them the art. I remember being more worried about the art that I was going to show. But again, that, for me, gave me the comfort of, speaking to adults. and speaking up your mind because these adults were asking me what I thought about things.

So I think you learn to form your own opinions early on. And I think again, that's been very helpful and a big part of my formative growing up.

Ling Yah: And is that why you were so drawn to the American liberal arts education system?

Azran Osman-Rani: Well I put it in as back out. Yeah, I think generally when I finished SPM here in Malaysia, back in the late eighties, you were told four choices, right?

Medicine, law, accounting, and engineering. And most people did the first three, which meant most of them would go to the UK some in Australia. And because I can't stand the sight of blood, so medicine's not for me. And I remember thinking the legal and accounting textbooks are very boring because they don't have pictures and colors.

So I wanted to choose engineering. And I think that in a way helped me skew my search towards the U S because the other part for me, less about the country, but more to be in a place where there were as few Malaysians as possible.

Ling Yah: And did the fact that you were terrified of snow have any part to play in choosing Stanford to study?

Azran Osman-Rani: Well, just probably a little part. I wouldn't say I'm terrified of it. definitely do enjoy holidays in snow, but what I know I'm really not a big fan of is cold weather, where you have to day in and day out, get up and go to school or get things done in freezing cold temperatures. So not a fan of having to live in very cold climates.

Ling Yah: So what was it like studying in Stanford in the early 1990s? Because this was before the era of Yahoo, google.com. Boom. So very, very different from what we know now.

Azran Osman-Rani: Yeah, it was different. Although it already had a very strong technology focus. And of course at that time, the poster child for Stanford engineering was Hewlett Packard.

Cause they were graduates, right. And of course Intel and some of these other companies, Cisco. But I think where Stanford probably left its biggest Mark with me was being exposed to just the breadth of knowledge that's available out there. Right? Because you come from an upbringing where these are the subjects and that's what you learn.

And suddenly the menu that you can choose from was massive. Topics that I had never even dreamt of or had not heard of before. And also in the us education system, you have full flexibility. And so even though officially my degree says electrical engineering, I'm pretty sure I did the barest of minimum engineering classes to get that piece of paper.

Everything else was, I remember history, culture, psychology economics, ballroom dancing, sailing, so many things to just get that breadth of ideas and being able to meet people from these very different academic disciplines.

Ling Yah: When you were in Malaysia, you used to do competitive field hockey, but when you went to Stanford, you ended up participating ultimate free speed.

How did that happen?

Azran Osman-Rani: Yes. Well you know, I remember going to my first year at Stanford and, say, Hey, look, you know, I do want to keep being physically active. And so I asked people in my dorm, Hey, so where do I play field hockey? And they gave me the puzzle look like field hockey.

Don't you mean ice hockey? Because only girls play field hockey in the US. Men play ice hockey. I'm like, Oh, okay. That's not going to be good because I can't ice skate saved my life. And ice hockey is a completely different than much more brutal sport. But I was still determined to kind of still be active.

And that's sort of where talked a lot of people and I found some people in my dorm who had just having a casual game of ultimate Frisbee that really fascinated me like a completely new sport. And what started off as just, you know, casually learning how to throw a Frisbee. I became quite obsessed about it.

I remember You spending late nights, well, in past midnight, just learning how to throw this Frisbee down the narrow corridors of my dorm, To make sure it doesn't fly away or hit at people's doors. And eventually then I guess I was pretty decent enough that someone said, Hey, you should try out for the Stanford team.

And I did. And that actually became probably the one activity in my four years there that I spent the most amount of time, like 30 hours a week with the ultimate Frisbee team. More like triple the number of hours I spent in lecture halls.

Ling Yah: And the final year was pretty significant for you as well, right? Can you share a bit about that?

Azran Osman-Rani: Well, because in my final year we became the number one team. In U S collegiate, ultimate Frisbee, not only that, but very rare. We were the undefeated number one ranked team, because in a typical season, we would have 50 games, right. 50 matches. And so to not lose a single one of that, it's very rare.

It's like probably once in a decade you have a university that It's, it's a bit like, you know, in English, premier league football, Where so many teams win every year, but how many teams win undefeated? I can only think of like Arsenal, I think 2003, 2004, right? So in the last, more than 15 years, no one else has repeated that being the number one ranked team, right.

We got to the national championships. Now, this was held in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, right. And when you're the number one ranking, everyone is looking at you and getting to take you down. And I remember the first five games in sort of the pool round. We won all five and then we got to the semi-finals and we won that game as well.

So now we're in the finals off the national championships in a season that we were completely undefeated. What was interesting though, was that the team that we were playing happened to also be the only other undefeated team in the country, never before where the two undefeated teams meeting in the finals, the last game of the entire season.

And this is a team we had never played against before. Right. So that's just so rare and they were from the East coast. So like normally we do have, you know, rare, but we do have a chance to play with teams from other regions, but this particular team, East Carolina never seen them before we heard about their reputation.

But anyway, to cut the story short was a very intense game. Then ultimate games were quite long, so it was almost three hours. And ultimately we lost 2017, so completely heartbreaking you know, the taste of defeat when you have that much pressure on your shoulders. And I like to say that well, it was because of that, that I resolved to do my masters, just so that I could have one more shot at another national championship.

And so the following year, we actually also got to the national championship at this time lost in the semifinal. So never been a national champion before.

Ling Yah: That's really unfortunate. After you finished your second national championship, I suppose you had to start thinking about what do I do with my life

and did you run out of eligibility?

So you got to go out to the real world scary as it is.

So you knew you didn't want to be an electrical engineer. How do you end up with consulting?

Azran Osman-Rani: Well, again because one of my senior teammates in the ultimate Frisbee team, he went on to become a management consultant. So Started talking to him amongst other people.

And he was telling me about, wow, look, you know, this is a really cool profession. We get to work on multiple projects, travel around and work in different industries on a wide range of problems. And it was that breath that excited me the most. I think what you'll find one theme over and over again in my whole life is I get bored easily.

I find it difficult to just focus on one thing. And the prospect of a job that gave you that breadth of exposure was something that appealed to me a lot. And so I became very determined to want to be a management consulting.

So another related theme besides having a short attention span and being interested in too many things is when I do decide I want to do something.

I get very obsessed about it. Like maniacally obsessed, right? Just like, okay. Oh, I've just discovered ultimate Frisbee. Like, I don't want to just learn how to throw a Frisbee. I want to be like one of the best ultimate Frisbee players in the country. And so when I discovered about management consulting, I'm like, okay, this is what I want to do.

And I started applying to all the different firms and got rejected one after the other, after the other. And I remember outside my college room, I had like this wall of shame, like 11 rejection letters. But you know, number 12, I got it. So yeah, like I think each time you get rejected, you learn from that process.

You're like, okay, I'm going to keep trying again. Keep trying again.

Ling Yah: Your 12th application was with Booz Allen Hamilton.

You ended up going to Singapore in 1995. And I think you were posted straight to Thailand after that.

Azran Osman-Rani: Yeah, pretty much once I settled in within a few weeks. They're like, okay, we're going to have this project in Bangkok and off you go, boom. So.

Ling Yah: That must've been quite exciting then.

Azran Osman-Rani: Cause he was, you know, like I was still in my early twenties I think, but now I'm like, wow, you know, I must have been a baby then or had and being thrown in the deep end and having to pretend I know what I be doing and being in board rooms with executives of an oil and gas company, it was just mindblowing now to think about it.

Ling Yah: In 1996, you were in such a boardroom presenting to the senior management of the Indonesian clients.

And you bombed that presentation.

Azran Osman-Rani: Oh yeah.

Yes. I don't know where you picked it up, but yes, that did happen. That was a really bad presentation. But actually it wasn't so much the presentation was bad, right. I think I acted unprofessionally because I reacted quite negatively to the client who basically disagreed with whatever I was saying and what my team was saying.

And this is where in life it's not about who's right or who's wrong. Maybe I was naive thinking that coming from an engineering background where you think there's always a right answer, there's always a formula and a solution to any problem, but in life that's not the case.

Solutions are not necessarily about who's right. But what matters is, do you gain people's trust?

That was a very painful lesson. Because I got pulled aside by my boss who said, look, one more time that happens. We're going to kick you out.

So rude awakening, but I deserved that kick in the butt.

Ling Yah: Soon after that was the Asian financial crisis. And you must have seen the nature of your work change a lot, because you're doing a lot of technical engineering things and now it's all about finance.

Azran Osman-Rani: Yes, yes. Yeah. Because of the nature, right.

Where people were urgently needed in Thailand because of the whole economy frankly, was under extreme duress. And so even though I had no financial sector experience, I got thrown into this project and I had to learn very quickly.

I remember those were the days before Google, right? So you can't find information on the internet. I remember like buying textbooks on corporate finance and credit management and going over these thick textbooks in my hotel room so that I wouldn't look too dumb in my client meetings.

Nowadays, any new topic, you can just do a quick Google search.

It's not, then the world existed before Google.

Ling Yah: So you learned all about that and then you eventually moved to McKinsey and in 2001, you moved your entire family and your three or child to Korea. How did that happen?

Azran Osman-Rani: Well, On one hand you know, we survived 97, 98 with the Asian financial crisis, then things looked quite well.

But then early 2000, there was this big.com crash. And I think Southeast Asia in particular, there was a bit of a setback, the economy, or slowing down and frankly all the client work dried up. and so the only real work that was available was in Korea. And Korea is known to be a very tough place to do business, especially as a non-Caucasian foreigner.

Then but there's no choice, right? Like if that's the only place that's hiring and they're still work, then you've got to do it.

And of course, Korea is far enough. You can't just come back every weekend. So it meant having to relocate our young family in Seoul and just again, being thrown into deepen.

And you've got to now figure out, like, learn enough Korean so that you can tell the taxi driver where you're going and, learn how to connect and build trust with people who, may not be trusting. So you've got to earn trust in a very difficult situation.

Ling Yah: So how did you actually earn that trust?

Azran Osman-Rani: Well, I think this time, of course I've learned to mostly listen first and talk less because of so many things that was happening, the one part that I was focusing on and leading was to help my Korean clients put together a three way joint venture with an American firm and a European firm now, two way joint ventures that across border in different cultures is already very hard.

Three way is even much more complex. So not only were there the technical aspects, like, the valuation and the financial considerations or the legal structures or corporate structures, but very important for me was, well, how are decisions going to get made? How will this business operate when you know, leadership is devolved across people from different nationalities and different time zones.

Right. So we had to like really think through how this is going to happen. and I think by again, spending time being that intermediary, because my Korean clients were not as comfortable to be forthright and communicate directly with the two potential partners. So I was the go between, And then to help listen to everybody and come up with ideas on how we can actually find the right compromise in each of like, probably over a hundred points that you needed, you know resolutions on. So that starts with listen more and then position what you want to recommend in the context of what is important to the other people.

Ling Yah: You must've enjoyed it enough to feel like you wanted to make it a more permanent move to korea.

Azran Osman-Rani: Yes. Yeah. Yes. I mean, because, you know, for the first time in my life, like I felt I was really seen as a trusted advisor, right? Not just someone who knows how to do slick PowerPoint presentations. you know what I then learned that real consulting was not in these presentations and decks that a lot of the young consultants focus on, but real consulting was when, after work, you go out and share a meal with your client and that your client trusts you enough to really open up about what his or her deep seated concerns and issues and problems are.

And then just wants to get your help to help them achieve clarity, or decide what to do. So not in the board room non-formal meetings or presentations, but in just kind of got quiet one-on-one conversations. And that was the time when I felt really being able to be valued by someone for my counsel, right.

Not just for my PowerPoint presentations or numbers or Excel spreadsheets. And that's why I felt look, you know, I, I really can see this, I really enjoyed that professionally. And so I said, look, I'm going to want to change my status in Korea from a visiting consultant to a permanent employee of the McKinsey Korean office.

Ling Yah: So what happened because you ended up returning to KL instead of staying in Korea.

Azran Osman-Rani: So it was the first of what would become a number of seminal phone calls because literally as I was in the meeting room or in the office of the managing partner of McKinsey, Korea, having a conversation about wanting to permanently transfer to the Korean office, his phone rings. Again, those times, yes, we had a few mobile phones, but they were very crude phone.

So most people used office landlines, right? This phone rings. And it was the managing partner in McKinsey, Southeast Asia, who said, hey, look, we've just won the mandate to advise the Kuala Lumpur stock exchange on this pretty complex restructuring exercise to turn it from a nonprofit sort of government linked organization to a for-profit company.

That would be a public listed company by itself. And it would be a very political and complex exercise. And we probably need some senior coverage to deal with a lot of the Malaysian political and regulatory leaders. And Azran's the most senior Malaysian we have in the firm, can we have him back, please, right.

And I said, oh, okay, well, shortly I go back and, probably just help the team kickoff and get started, but I really wanted to come back to Korea. But then sometimes in life, you start down one path and you think it's temporary just like Korea.

And if it was temporary this time that work to not, to be really amazing also to be again, being seen as a trusted advisor of the executive chairman of the stock exchange, where he then eventually said, Hey, no one understands how a privatized for-profit stock exchange should work. I don't have the resources to keep hiring McKinsey to advise me. I wanna, you know, have you join me as an employee, right. And show me that you can turn your ideas into reality. So don't just advise, but do. And that was the first time when someone, when you put it to me that way, right.

It's a bit like, don't just learn how to throw a Frisbee, but like be really good at it. So the idea of, Hmm, after almost 10 years of just being an advisor, now, someone saying look, advice doesn't get too much, right? Like you've gotta be able to do it. And here was an opportunity from someone that I had a lot of respect for who said, I think you should do this.

And so I did. So I quit McKinsey and joined my client.

Ling Yah: So this person was the former executive chairman, Mohammed Aslan Hashem. And he didn't just give you the challenge. He asks you to take a 50% pay cut. So it was course.

Azran Osman-Rani: Yeah. Cause we don't pay McKinsey salary.

So this is all I can offer you, right. And you got to take it. So I'm like, Oh, okay.

Ling Yah: What were the highlights from that time for you?

Azran Osman-Rani: Oh, so many things. I mean, clearly at first life was a lot more sensible because instead of flying around every week, like a mad person, I think for that year and a half, I was only in, Malaysia.

I mean, I had to go to few other places in South Australia, North and South peninsula to meet stakeholders, but nothing like having to go to the airport and travel around the world. So system much appreciate that stability in my travel schedule.

The other thing for me that was like, wow, was the whole experience of dealing with the Malaysian parliament because to give effect to the corporatization and privatization of the stock exchange, we needed to have five bills passed in parliament. Five, right.

And I had to deal and it was complex. It was like the Securities Industries Act. Malaysian derivatives exchange act and the Malaysian securities clearing house app, et cetera. So these are complex pieces of legislation. And actually, I think the minister of finance and the deputy minister of finance just had no interest in it, right, because it was just not very exciting.

and I was left with the newly appointed deputy team finance minister to write who had just transferred from being the deputy tourism minister. So her name was Datuk Eng Yen Yen, and she just got this role and her senior store. It's yours. You got to now shepherd these five bills.

And a credit to her.

She took on that challenge and I had the privilege of having to sit in a room with her, like all day explaining to her, like these are all these bills worked. And I remember then also being in parliament that one day that she had to debate and convince the other parliamentarians to vote on it. And when she, got questions, you know, from the members of the opposition or, even her own party, like, I had to like write answers on a piece of paper and pass it to her you know, and in Bahasa mind you, cause it's in the parliament.

So that, again, like it's one of these things you do once in your life. Right. And I know some people make a career out of it, but well, definitely your regular corporate experience.

Ling Yah: So not long after Mohamad Azlan Hashim left, you also left to join Astro. So how did that happen?

Azran Osman-Rani: Well, another phone call.

And again, right, because he's like, well, you know, I think you should be, you know, like the CFO of this new listed company, I'm like, you know, okay. But he then said, well, but I'm retiring. I'm going to go play golf. I'm like, Oh, but I joined because of you. Right. Like if you're not going to be here, I don't know whether I want to stay.

And again, in life suddenly when you're in that period of like, Hmm, do I really want to stay or not a phone rings? And someone said, I want you to meet the CEO of Astro, like, okay. at that point, Astro had also just completed their IPO. They raised a, I think 2 billion rugged, and they want it to go from being a Malaysian television, broadcast it to being a regional television broadcaster.

So they didn't want it to make a lot of investments across the region and said, whether. I want it to lead that effort as well. Okay. Well, I don't know anything about broadcasting or entertainment, but I'm game for a challenge. You give me a challenge. I want to take it. So that's what I did.

Ling Yah: I imagine for a lot of people, the idea of having to restart and learn an entire industry from scratch is daunting.

So can you give us an idea of how you started that journey? Cause you didn't know anything about tech.

Azran Osman-Rani: But what I had a lot of experience by then was learning about new industries, right? Because again, I come from an engineering background and first I had to learn oil and gas. Then I had to learn steel manufacturing.

Then I've learned banking, right then telcos. So this is something new and again, right. By then there was probably Googled, but there wasn't the richness of information available. A lot of it was textbooks. A lot of it was finding out who are the smart people around the world and how do I get connected with them and ask them a ton of questions.

And so it was hard work to learn, but, you know, I think I kind of enjoyed that, right? Like just the discovery phase.

Ling Yah: So one of the things I've picked up is that for Indonesia in 10 months you hired 450 people, you built five Indonesian, cable channels, launch a national sales and distribution network builds a broadcast center. A lot of things that you achieve in just 10 months.

But then you often say as well, that one of your big failures was that you had to shut down the business and let go of 450 people.

And I wonder, you know, looking back what happened and what kind of lessons you derived from that experience?

Azran Osman-Rani: Well, again, number one lesson is real business is not what you write on a business plan. Because, you know, so many people spend so much effort trying to have the perfect business plan, the perfect ten-year cashflow models, et cetera, but you can plan all you want.

But in life, it's not about what's on paper, but it's the relationships that you form. And also when it comes to relationships, when things are rosy, it's always easier to come to an agreement, you know, make decisions together. But it gets tough is when real differences of opinions come into play.

And that's when conflict comes in, right?

And so in this case you know, the two principles the Malaysian principle that I represent an Indonesian principal didn't get along, right. They just have some fundamental disagreements and that led to a mutual decision not to continue to fund this new venture and without funding you die.

Right. So that's the reality. That relationships can appear to be strong initially, but if it's not nurtured and not maintained, it will fracture. And these are the consequences.

Ling Yah: You were 36 in 2007 when you became the CEO or air X. How did that happen?

Azran Osman-Rani: Another phone call. Because once the decision was made to effectively pull out of that Indonesian business, right. I'm kind of get stuck. Okay. Well, what do I do again, in life phone call comes in and someone says, I'd like to use to introduce you to a gentleman by the name of Tony Fernandez.

I was like, Oh, who is? He didn't even know, like know I was thinking, am I going to meet some kind of expat guy. Turns out he's another Malaysian from KL. And so that's that's life, right? Like random phone calls happen. And I think it's mainly because rather than kind of look for opportunities, but if you focus and doing what you do, and you really are obsessed about it, I think your work will speak for itself.

And then people come and look you up.

Ling Yah: And were you intrigued right from that conversation that this is something you wanted to enter into?

Azran Osman-Rani: Well, mainly because, I mean, first of all, Tony's a probably bar none, one of the most amazing salespeople, right? Like if he wants to sell you on an idea or a concept, you're going to get convinced.

But what really intrigued me was when he said, no one in the world has ever done a low cost long haul model, all the experts in the industry say it cannot be done. We should try just for the sake of proving the world wrong. Right. And so I guess he knew which buttons to press with me. Right? Like, when you frame it as that challenge, like how can I not just drop everything and say, all right, game on, let's do this.

Ling Yah: What was it that you felt you could bring to the table that was different? Cause you had Freddy Lakers. You had Oasis Hong Kong, even AirAsia itself. You had to license the brand from, because they didn't believe in you.

Azran Osman-Rani: Well, ultimately for me, number one, it's the curiosity to look at things differently. To challenge a lot of assumptions.

But I think number two, very important as a leader is how do you paint a compelling picture that convinces people who have the real experience and industry expertise to come on board, this mission to go along the ride with you because you can't tackle these problems by yourself, right? And so you do need to rely on people who are much smarter than you, but our job as leaders is to convince them why they should leave their established organizations and join you on, crazy missions.

And so that's part of what we have to do, right? We have to be very compelling. We have to be very persuasive. And if you assemble the right team, And you excite them enough about this idea of doing something that no one in the world has ever done before then I think that's a big part of where the magic happens.

Ling Yah: So once you had that right team, how do you go about figuring out a model that was sustainable?

Azran Osman-Rani: Oh, I think ultimately it took us years to really understand you know, how do you create a sustainable airline? Of course, a lot of people will immediately and they have every right to say, but, AirAsia X never figured out because they only look at it from an external overall consolidated P&O.

but I think internally, because we could look at, for example, the profitability of our business by individual routes and destinations that we flew to and which types of plans we found, and we were very clear what drives profitability, right?

In this case, You can only be profitable in markets where you are the number one player. So you got to choose which markets to compete in and you have to play to win. You can't play to be number two and number three. So what does that mean? Right? That means it's better to be a big fish in a few ponds than a small fish in many ponds.

And once you've figured out the formula, we then embarked on this pretty massive restructuring exercise. We'd pull out of Europe. We canceled our London and Paris routes. Most people thought, Oh, you know, see they're withdrawing so long haul doesn't work. Actually. It's not about the distance has nothing to do with the distance.

It has everything to do with, better to, for example, be the number one airline flying into Australia or Japan or Korea instead of, you know, one flight a day to London when Emirates by themselves eight 8380 planes flying to London every day, right? So you got to choose where you play and then you've got to win.

And when we were able to demonstrate that model and execute that model, we were able to convince pretty sophisticated investors in 2013 to say, okay, I will buy your IPO shares because your explanation makes sense. Right? And so ultimately to me, the validation is not just because I think low cost long haul can work, but we were able to build a case and convince very sophisticated investors that yes, it can work.

Now ultimately, of course you know, 2014 became no one predicted 2014 that within less than a year of our IPO, the whole aviation sector went upside down. Because of what we call black Swan events, right. Things that are highly improbable, but when they happen, they have massive impact. So March 2014, MH 370 a plane went missing July, 2014, a plane was shot down over Europe.

And then in December, a plane was lost en route from Indonesia to Singapore, all of them, while they're not AirAsia X, they're a tremendous effect on our markets specifically out of China and Australia demand plummeted by double digit rates, right. In the first year as an IPO or Lyft public listed company.

And she never recovered from that. So that's life like you can go through the hard work, figure out what works, what doesn't work, convince people, and they give you capital. But yet who would have predicted 2014, just like many people didn't predict it. 20, 20, right?

Ling Yah: But even before 2014, I mean, it seemed as though you were hit by unfortunate incidences all the time.

Beginning with 2008 financial crisis.

Azran Osman-Rani: Eight 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012. That's how I lose all my hair.

Ling Yah: So tell us about 2008. Cause that's when the oil price went crazy, right. And it really impacted them.

Azran Osman-Rani: Yeah, because we launched in November, 2007. And literally just a few months after we launched, the world turned upside down because first you got to deal with the global financial crisis where banks who have even signed agreements to provide financing to you all pulled up. Hung up to dry and trying to like, how do we even survive this without financing?

And at the same time you're dealing with that crisis, another crisis built up, which was oil prices. Now for an airline like ours, oil is almost 50% of our cost. Right. And oil went from, if you think about it, 2007, you put a business plan together. How do you decide what's the price of oil in your model? You look back and you see, Oh, 2002 to 2007, or it was about 50 to $70 a barrel.

Let's be a bit conservative and call it $75 a barrel, which is what we put on business. And in the first six months of 2008, it almost doubled to over $140 a barrel. And this is where again, airlines started panicking. And what do boards and investors tell you to do?

Hedge your fuel, right?

What does had you mean hedging? People say, well, it mitigates your risk. Actually what's meant to be a risk mitigator, turned out to be a risk creator because by fixing the price of oil, when, when you say, ah, okay, no more volatility, or let's say oil is now $90 a barrel, then you go to the back and he say, I don't like volatility I want to cap my price of oil for the next 12 months.

Okay. A hundred dollars a barrel fixed price. Right. And then of course, after that kept going up all the way to $140 a barrel by July. And you're like, wow, I'm really smart. Right. I took away the volatility. I avoided all this. Then from July to December, 2008, it crashed all the way under $40 a barrel. And you've locked in your price of oil at a hundred dollars a barrel.

So just dealing with those issues, it was just insane, right? Like again, nothing that's ever been written in textbooks and no one could have anticipated it.

Ling Yah: I mean 50 airlines went belly up, but you didn't. So how did you pull through,

Azran Osman-Rani: Oh, I like to use the term sheer dumb luck because it just so happens that the bank who was the counterparty to our fuel hedge, they went bankrupt before us.

Ling Yah: And then before that, you actually secured this meeting with this European export credit agency in London, and that was sort of like the pitch of a lifetime for you. Can you share a bit about that experience?

Azran Osman-Rani: Well, so remember when I shared that, early in the year, the banks who had signed legal agreements to provide financing all pulled up, right?

So now there's no more financing. No more financing, how do you get planes? No planes, you know, no airline, right. And at that point, the last lender, lender, lender of last resort, Was the European credit agencies, because they want to support European exports in this case, Airbus. Right. Because if we can't buy Airbus planes, then of course, Airbus are also not going to be in a good position, but the European export credit agencies usually have a rule, right?

Like they only provide their credit guarantees to airlines with a three of profit track record. Number one, we've been in business less than a year, and we're definitely nowhere near profitability. so first just somehow getting them, convincing them to just even give us time for one meeting was already very hard, but somehow we get it.

And I remember flying up to London, preparing for this presentation. Taking the London underground to their office in Canary Wharf. And while I'm in the subway, you can see most people are reading newspapers, right? And the headlines of that newspaper was literally another long haul, low cost airline had just gone bankrupt.

If you remember, airlines were going bankrupt one after the other, right. I'm like, okay, so here I am going to the export credit agencies to pitch why they should support us. A fledgling long haul, low cost airline with no profit track record when just that morning, another one had gone bust. So I thought that was really ominous.

But you know, this was the last chance. There was nothing else, right. If they said no, and he had every right to say no, that's it, it would have been game over for us.

Ling Yah: To say yes.

Azran Osman-Rani: So I honestly don't know, because I remember that day, I was just really just running on adrenaline, but I have no recollection of what I said.

Because he was just all adrenaline. And I remember after that, where I look at this committee, they're very like stoic new expressionistic. We will come back to you in a few weeks. Okay. And you go back and you're like, crash. I don't know what I said. And six weeks later they did come back and said, they will provide us guarantees very difficult terms, but at least it was a lifeline.

So that's life.

Ling Yah: I feel like, you know, in what you've shared so far, it's very clear, no matter what plan you've made, it just doesn't work out. So that's probably why that's probably why you always say I don't have a long-term plan, but you want to be flexible and nimble all the time.

Azran Osman-Rani: Cause you have to, it's not by choice.

The world dictates it that way.

Ling Yah: I loved some of the things that I noticed during your tenure. One of the things that you were really prioritizing, the fact that information was flowing up to you to ensure that you would be nimble to respond to things that other larger airlines will not be able to.

Can you give an example what that was like and how you ensure that you went up? Cause you scale very quickly to 2,500 staff. That's a lot.

Azran Osman-Rani: That is a lot, right? And it's one of these things where you learn somehow naturally silos get formed, right? People start to not talk or communicate, or it only happens at certain meetings.

So information has to go up before it can come down. So number one, that is. Very slow and very inefficient. Right? And so as a leader, what I learned is, number one, you can't just say, Oh, come to me. If you got a problem, no one's going to come to you. Or if you just go and try to say hello to everyone, you know, management by walkabout, that best you would just get, Oh, everything's good boss.

Like, no one's really going to stop you and then have a deep conversation with you. Or if you have a town hall meeting, right. And you say, all right, guys, this is the plan for the quarter. Any questions? No, one's going to prep the hand and say, as a leader, you can't say, Oh, well I've done my part. It doesn't work that way because there's still a lot of issues and problems and frustrations on the ground.

They just not coming up to you. So therefore, as leaders, we have to figure out what would it take for us to get in there and bring the information up. And so that included things like having what I now call honesty hour sessions, basically just forums where you provide your employees, the safety of anonymity.

Where people can say anything that they want completely anonymously and confidentially. Like either they just write it down or we use anonymous Google forms, but then like real unadulterated problems start to come up. Now, the first few times you do this, people may not believe you. They may not trust you, so they may not bring up much.

But what they're really doing is they're testing you to see how will you respond if they just throw a small problem at you? Because a lot of times leaders, right? When an employee throws a problem at you, your first reaction is to be defensive to explain the problem away. Oh, well, the reason why we can't do it is because we don't have enough budget and waiting for this approval or that.

And so If you take that position next time the employee is going to, huh? What's the point of surfacing issues because I'm just going to get blown off. But if you're committed to the process and you're committed to win over the trust of your employees to say no matter what the issue is, even if it is like I'm upset because we ran out of cookies in the pantry and you take that problem seriously.

And if that were on a Friday, by Monday, the cookies are all stopped. So the next time we're only placement go, okay, let's try a slightly bigger problem. Right? So it comes back to the first principle I said earlier, which is you've got to earn trust as leaders. You can't demand it by just the sheer position or authority that you hold.

Ling Yah: Wasn't there example of the aircraft stuff was saying that there were wheelchair people on the plane.

Azran Osman-Rani: Oh, that story. Yeah. Well, because again, it's a good example of a problem that I never knew existed where like the flight attendant started to complain that when her flight ends, she arrives back at the airport and she's got to wait until all the passengers disembark before she can leave.

But if there's someone in there who is, needs a wheelchair and it's quite common, one of every three flights, someone does need a wheelchair and that wheelchair is not there the door. And if it takes longer than five minutes, if it's like 20, 30 minutes, that wheelchair is not there. You can bet the passenger is going to be very upset.

And guess what? The passenger is going to start scolding the flight attendant through no fault of him or her. Because it's another department's responsibility, the ground operations team.

And so first it was through this process that we'd discovered it. We had no idea even existed second. Oh, I have no idea how to solve it.

But by bringing on the open, then you start to realize, well, the ground operations team start to get defensive. Look, it's not a problem. We don't have enough budget, not in a manpower, not in a wheelchair. So we can't be at the gate at every single gate because as they say, we can have a plan, but the flights don't come exactly on time.

So you've got to move around. And so we've got to tactically reallocate our resources. Our very limited resources and sometimes some Gates get missed for 15 minutes or 20 minutes or 30 minutes. So if you want us to solve it, give us more manpower and more wheelchairs.

Well, okay. That was the only way to solve every problem, which is just to throw money at it.

Then, you know, obviously you're not going to be able to be very successful in business, but that's also where because we create the right forum where people from other departments heard about it and they say, Oh, one in particular, the engineering guys at, Hey, interesting. We never knew you guys had the problem.

But he has an idea, which is doesn't matter where the plane is early on time or late when the plane comes in, what will definitely be there when the plane comes in is the engineering van, because in the engineering van is the guy that holds the two lollipops, right? There's lollipops crossed the pilot nose, press the brake.

The wheel will stop exactly on this line, painted on the tarmac. Lollipop man puts thumbs up and the aerobridge will fit nicely on the door. So the engineer said, what if we kept a backup foldable wheelchair in the van, so that if ever the main grown-up patients, wheelchairs, late flight attendant, get the back, that wheelchair sort, your client out your customer at first, they're happy.

And then let the ground operations team catch up.

No one thought about that as a solution because we always, you know, organizations, we just think within our own resources, right? Ground operations. Doesn't think about that being a solution because the engineering van is not in their department, not under their P and L.

Ling Yah: And another one I noticed you said before that you didn't wait for customers to make decisions. You went to their face and told them to fly to places they hadn't dreamt up.

How did you do that?

Azran Osman-Rani: Well, I mean, to me, it's, this whole concept of you have to create demand because if you only wait for demand to happen, you will always be reactive.

And I guess for me, probably the thing that really brought this concept to light was our route to Chengdu in the Sichuan province in West China. Because when we started flying, most Malaysians had never heard of Chengdu. When they think about going to China for a holiday, it is Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, right?

Like Chengdu. What's there in Chengdu. And consequently for over a year, that route lost a lot of money.

And I had a lot of pressure from my board. Like just stop flying that you're losing money with every flight, but somehow I kind of felt that if only people knew about what you can do in Chengdu. There are panda bears, beautiful places that You Chai Gou. The Sichuan cuisine, right?

There's so many things, but you've got to like really communicate that out and figure out how do you create demand that didn't exist before and eventually changed? It became one of our most profitable routes because it was always full of people going to Chengdu of coming in from Chengdu.

But it took a lot of like, you know, 18 to 24 months to make that work.

Ling Yah: What were the things that you found most effective in creating that demand?

Azran Osman-Rani: As a marketer, what I've learned is we're actually not very smart. We can't imagine or put ourselves in, in our target audience.

Traditionally market is always thought, right? Like, Oh yeah. You know, we're smart. We look at, research and yeah, this is what our customers need. But actually I was, I'm a believer now in the saying like, can't know for sure, but let's try so many different things and then just see what works and what doesn't work.

And I think this is also why, 2008, 2009, then the internet and it just started. So you could now run many experiments and that's the power of advertising over the internet. You don't need to like, just have many billboards or TV commercials, but you can put different ads, different messaging, different creatives, and see which ones work.

And then you adjust and you reallocate your marketing spin to the ones that give you.

Ling Yah: And one of the things that I've noticed as well is that you also made some mistakes. There was a $15 million mistake with the in-flight entertainment.

You share with us about that?

Azran Osman-Rani: A lot of mistakes. I mean, that's just one tiny example. But the point is when you try to do something new, when you try to do something that no one else has ever done before, it is impossible to always get it, right.

Like many organizations, if you don't tolerate failure. Right. And so you must get it exactly right. Then you launch, but then you lose out on speed.

So ours was a philosophy that looked just pry quickly 10 things. And even if eight out of 10 fail that's okay. We move on. We learn. So one of the many examples was we thought we would be the first low cost airline in the world to have full in-seat flight entertainment screens and the back of every economy seat.

So if you were actually in an AirAsia X plane, not AirAsia. AirAsia X plane 2008, 2009, you see these not just the regular in-flight entertainment screens, but then things like touch screen was quite innovative, even had instant messaging. So that on the plane, your board, you kind of liked that person on row 13 G you can send a message.

Hi, 13 GM at 17 F, nice to meet you. That part was popular. Your pre-order your meals. So you don't have to wait for the flight attendant to come with a cart to ask you what you want. You can just kind of select your meals.

That again good idea. In theory, turns out though it became a terrible customer experience because number one, you learn, people don't want to eat at the same time.

They just eat whatever they feel like it. And when they do buy, they want it. Now they don't wait 15, 20 minutes. But the problem then becomes, okay, if all your orders go straight to the galley and the flight attendant now has to go 14 G once a code 13 F once a hamburger, 22 D wants chicken rice, right?

And then 17 C wants nasi lemak or suddenly the whole system kind of just fell apart. customers were upset. Even the flight attendants were upset. but the single biggest reason though, was we thought, Hey, we've got in-flight and team screens. Maybe we can put in TV shows and movies that people just pay a small fee.

Let's say, $5, $10 would they watch movies? It turns out though, actually many people refuse to pay money to watch TV shows, right? But yet every single plate, every single screen, every single movie title, you have to pay a royalty fee to the Hollywood studios. So now you you're starting the flight with this fixed costs from all these royalty fees.

If you can't sell enough, you're going to lose money. But if you set your price too high, less people will be willing to pay you set they're price too low. You can't cover your costs. And we ended up losing a ton of money just from the TV entertainment systems, let alone all the issues about food ordering and all of that.

And so we ended up having to scrap that whole system. It was a 12 million us dollar write-off. So that's about 50 million ringing down the drain.

Ling Yah: You were trying many, many different things and you scrapped those that don't work, but you also need it to run for a time to see whether itwould or would not work .

So how did you balance and juggle these different initiatives and then decide, okay, it's done. This is not going to work. It's time to change.

Azran Osman-Rani: Yeah. That's a very good point. And I think as a leader, here's what I learned. Number one, very hard to evaluate an initiative on a standalone basis, right?

Like, because sometimes you just gotta be resilient. You've got to persevere, keep being creative, right. Find a way around all the obstacles. But what point you call it quits.

So what I've learned is while it's hard to evaluate on a standalone basis, it is easier, not easy but easier to do it on a relative basis.

That means if I stopped doing that, do I have a better alternative? I need to be convinced it's a better alternative, better use of my time, my focus or my team's focus, our capital, our resources, So you need to develop a better plan B. Then it's time to switch.

Ling Yah: So you definitely figured out some things that most certainly worked like the, low cost airline flatbeds.

And I think Singapore airlines initially said, Oh, this is not going to work you know, not bundling entertainment. They even hired your commercial director in the end because they saw it worked.

So how did you stay ahead of the curve when all your competitors were watching you and copying what you were doing once they saw it worked.

Azran Osman-Rani: That's okay because by the time they copied, that means they're looking at what we've already done. So the only way you survive is you're working on the next thing, right? Because even if they heard, Oh wow. They launched the service. Okay. We'll take them a few months to launch it, but you're already got like two or three things that you're already in your pipeline.

So there'll always be behind you. If all they do is they copy. And that's why I'm not a believer in this whole let's do industry benchmarking. Let's look for case studies before we do something, because that means you'll always be a follower, right? Like I think you've got to have the courage to do new things that no one else has ever done.

Ling Yah: So you're doing all this and you've achieved a lot cause you IPOed in June, 2013 with a one, $1 million valuation. So how did you end up moving again to a totally new industry? iFlix.

Azran Osman-Rani: Well, I think what I learned is that the things that I'm good at and the things I'm bad at, right, I'm probably better at the early stage, the ideation, the willingness to try new things.

But when something becomes very big, like a billion dollar company you know, it's publicly listed, that's got audit committees and risk management committees and much more conservative because you have something to lose. They probably by then need an adult to run it. And I'm the crazy kid that just keeps rocking the boat.

So time to pass the helm to kind of more responsible adults. And when I caught up with my former friends, Patrick Grove, who's the founder of Catcha and had this crazy idea of building iflix, didn't take a lot to convince me, right. We just paint a crazy vision. Like I I'm all for it. Right. Let's just let's do it.

Ling Yah: I think it started with this Monday morning conversation in Starbucks with Mark Britt, right?

Azran Osman-Rani: It was coffee. It was in Bangsar shopping center. It's not Starbucks. I can't remember where maybe then I don't know, but yeah, it was just one coffee meeting. And then that afternoon we went over to Patrick's office and we just started brainstorming right.

A whole bunch of stuff on the white board. And I'm like, all right, I'm going to sign up, let's do this.

Ling Yah: What was it that allowed you to make that decision? That this is why I want to jump into the next?

Azran Osman-Rani: Again it is, when it was, you have this vision in your head of something that doesn't exist before, that could have a big impact, right?

And I think one of the key insights was in media. You realize that all these meet gigantic media companies, but they actually are very parochial. They're like big and Malaysia, only a big and Hong Kong only are big in Singapore only. Because media had always been very regulated licenses and local ownership requirements.

That's why media was always a local industry. But the internet now gave us the opportunity to truly democratize it, to be able to access any consumer from Dakha, Senegal, all the way to Denpasar in Bali. And so that meant suddenly, instead of, for example, buying content for 30 million people, you can negotiate with Hollywood studios to buy content for a billion people.

Very, very different economics. No one had thought about serving the mass market in emerging markets that way. So. I'm all game for crazy things. So I jumped in.

Ling Yah: And so you started in 2015, you have few people, laptops, no product. What was the game plan to kickstart iFlix?

Azran Osman-Rani: I don't know whether we really had a plan. We were just constantly firefighting along the way. I remember initially we were like, okay, I think we can start in March. Oh no. Miss that deadline. Let's start in April LA, miss that deadline. Let's start in 1st of May. Oh, missed that deadline. 15 may miss that deadline, but 26 May, 2015 at 6:00 PM.

We went live. Mainly because number one, you do put tight deadlines. You try. Try knowing that, okay. If we fail, we fail, but we learn from it and we move on. Right? It's willingness to just kind of go fast and build basic version of a one. And basic version of one of iFlix was pretty crap, but we just want just put it out in the market cookie, test it out and then keep iterating, keep relentlessly iterating.

Ling Yah: And was local content something that you were considering that you really wanted to produce. Cause I think 50% of content budget went into original productions.

Azran Osman-Rani: Oh, I don't think it was ever that high 50%, but it was significant. Yeah, we wanted to. We knew it was going to be very distinctive mainly because the whole iflix proposition is to address that mass market segment.

Take for example, in Malaysia, If we sit here in Kuala Lumpur and fancy places like Bangsar or Damansara, right. You think, Oh, football is English premier league, right? Everyone is either Manchester United Chelsea, Liverpool, arsenal fan. But actually in Malaysia for every one person that watches English, premier league four or five people watch Malaysian football.

And they don't connect.

So it's a completely different segment. So simply pushing Hollywood means you only cover the segments in Kuala Lumpur, but you're going to ignore the segments that are much, much more larger and much more local in their requirements. So that is why we felt it is important to be distinctive with local content.

But the thing about local content is there's not a lot of it existing immediately. So you've got like produced stuff on your own and that's hard. You can't do it immediately, right. It just takes a long time to build it up.

Ling Yah: And what about just gaining that kind of support from the customers because within six months after launch, you got a million subscribers. Two months after it was a million and half.

So I think for anyone with a new idea to get any amount of subscribers, let alone a million is huge. So what did you do? Like what was the game plan?

Azran Osman-Rani: I want to tell you the game plan that we started with completely failed, right? Because we thought initially, okay, well, if a typical satellite TV subscription is a hundred ringgit a month, we imagined if we only offered 10 ringgit a month, surely we'll get a lot of people.

It turns out, next to nothing. Only my own friends and family member, so that I kind of forced them to subscribe to iflix. So initially hardly any take-up right. And then you're like, you have to know problem solver.

What could be the problems maybe? It can't be price-point. Maybe it's the payment channels, right? Maybe people don't find it convenient to use a credit card or online banking. Okay.

What are they familiar with?

So back in 2015, the number one payment channel for e-commerce, for example, e-commerce is growing very fast, right? Which is cash on delivery? Right. Okay. This is all before he wallets and all of that, right.

And cash on delivery. How does that work with athletes? So we had to experiment. We said, okay, at the end of your 30 day free trial, we will send a guy on a motorcycle to your home to collect your 10 ringgit. It costs more than 10 to get to pay the guy on the motorcycle to go, but we did it anyway.

Because we needed to learn and you know what we learn, they still didn't want to pay. So, Hmm. Okay. Well, if that doesn't work, then what else, right? And just so happened someone came up to me and said, hey, look, thank you for launching iflix I'm a big fan. And I watch it two or three hours a day.

I'm on my fourth free trial so that, oh, so they like watching iFlix. They just hate the idea of paying for it. So no matter what payment channels we put in, they wouldn't have paid for it. So that's where we then had to broaden the problem thinking, well, if the end user doesn't want to pay for iFlix, but they do like watching it.

So who will benefit if more people watched iFlix?

Now, most people think advertisers. But what I can tell you is like, if I have to stuff you with ads, you're going to run away from the app platform, right. Because now it's going to be annoying. Instead we say, well, actually, Telecom companies would really love it.

If people watch iflix because they were going through this like change in business model where, you know, 50% of their revenues, voice calls, SMS would disappearing and only data revenues were growing. And video is the most data intensive application, right? 70% of all data bandwidth on the internet is video.

So we gave video applications for free. They will want to use up a lot more data. And so that became the model, which was convincing telcos to buy iflix subscriptions from us and give it to their subscribers for free to stimulate more data usage, and then buying more data at a higher price than they're paying for iflix.

And of course, when you work with telcos, they've got millions and millions of customers. So it became a much faster way of rolling out than us, trying to spend money on Google and Facebook ads and convincing people to download iflix one at a time, and then convincing them to pay us 10 ringgit a month that would have taken forever.

Ling Yah: I mean, I just thought it was brilliant the way that you've bundled. It is sort of like in AirAsia, you bundled your offers with hotels and now in Naluri as well, you bundle it with your other companies like insurance companies. And in all of that, right? Why was rapid expansion such a huge, huge priority?

Azran Osman-Rani: I think because the reality in this world is you remain small. You're going to get crushed. And mainly because the businesses that I chose to compete in right airlines or entertainment or healthcare, these are big budget industries where scale matters. So while you might be able to start small, you're not going to last for a long time being small.

So you've got to fight for scale, and that's why being able to move fast is crucial.

Ling Yah: So in 2015, you ended up going to send Francisco to visit some or Stanford mates, and you ended up learning about Omada health. Can you share a bit about that?

Azran Osman-Rani: Well, so again, full circle in life that we started talking about ultimate Frisbee and one of my ultimate Frisbee team members was a co-founder of a company in San Francisco calamata health.

And we went there for an ultimate Frisbee team reunion. I caught up with him and he was telling me about his business. I was like, ah, it's very similar to what I do. I'm using a digital marketing to get people addicted to mindless TV it's teaming, and he's using the same digital marketing to get people addicted to a healthier lifestyle.

That's kind of more cool, right.

But also because they were very focused on diabetes and it really connected with me on a personal level because. Eh, 10 years ago, I lost my own father to diabetes. So that kind of opened my eyes in terms of how digital can actually really positively impact people's lives.

Because the other thing also, unfortunately, coming from Malaysia is we are the number one most unhealthy country in Asia, right. In terms of our rate of obesity and diabetes. So that got me really fired up and I see it to say, okay, well, you know maybe I want to do something like Omada health for Southeast Asia.

Because again, when we started iflix everybody wrote a staff or at least 115 investors wrote us up because they said this already a global giant called Netflix. But we showed that if you create something local relevant for the mass market, there will always be space. So same thing, right? Like Oman is great, but Omada is not tailored to the Malaysian consumers, the Indonesian consumers, the Thai consumers, the Filipino consumers.

So there's an opportunity.

Ling Yah: Were you thinking about this immediately after seeing Omada? Cause you went in 2015, you launch in 2017. So that's a two years.

Azran Osman-Rani: Of course, sometimes things percolate, right? The seed is planted, but I think the catalyst to me was in 2017. I mean, it was, you know, it was tough, right.

Because you know, we went through some challenging periods you know, kind of trying to keep the company float had to even like retrenched staff and, you know, trying to just survive. But ultimately we like suddenly raised $19 million and now I fix it a lot more capital to expand. So I felt incredibly relieved that that happened.

And just so the day that money came in, like, I remember. 28th, February, 2017. Wow. Like, you know, after like surviving, like you don't know whether you,willyou know, whether we ever pull it through and finding the light appears at the end of the tunnel. And then first, March, 2017, you just have a random conversation with a friend about your purpose in life.

Right. And he gave me this icky guy framework and guided me through it. And that's kind of how I kinda like, you know what, this reminds me of my conversation in San Francisco in 2015, I'm going to actually now commit to building it. Now's the time.

Ling Yah: I mean, you really, really committed. Cause you've said before you went, all in and you bet your kids' education, your life savings, everything into this idea of Naluri. Why?

I mean like, that's a huge bet at the, you know, it's not as though you have just started your career. You already have kids. Yeah. And everything else.

Azran Osman-Rani: Yeah. Well, to me, I feel like if I'm not a hundred percent convinced, there's no way I can convince anyone else. So I need to be like mentally all in.

And mentally all in there's theoretically. Yeah. Yeah. I'm convinced. But the only way you can truly convince yourself is what are you going to put online to really back what you believe, right?

And this is where I felt, okay, you know what, this is what I'm going to do. Like just kind of figured out how much I've gotten my son, different savings accounts and cobble this stuff together and just go launch. Commit.

Ling Yah: So one of the unique things I read about Naluri is that it's more activity based as opposed to results, oriented.

Can you share-

The

Azran Osman-Rani: other way around. Results.

Well, because again, I'm obsessed with problems, right? What are the problems that big companies are not solving right now? So when it comes to health, because of the experience of my father and learning about what Omada does, I didn't realize that there's this category of health called chronic conditions.

Chronic conditions are conditions like diabetes and heart diseases or cancer or mental health that you cannot solve with a single visit to the doctor. The way if you broke an arm or you had a flute, you can solve it. Those are called acute conditions, right? But the whole healthcare system was really designed for acute conditions.

You make an appointment or you go to the hospital or clinic and you have a session with the doctor and the doctor kind of gives you a prescription. Then you go away. But chronic conditions cannot be solved with one-off conditions, one off consultations. So you need a different model of care.

And the second thing you realize is that health care has been so specialized that every healthcare professional looks at your health, only in tiny silos.

The cardiologist only looks at your heart. The gastroenterologist only looks at your gut. The psychologist only looks at your mental health or the dietician only looks at your, what you eat, but when it comes to chronic conditions, they're deeply interrelated. And again, right. As you know, now, as I start to understand that, I realize that when, you know, my father died of diabetes and cancer, you know, the journey was extremely challenging.

You look back now, you're like, Oh, depression and anxiety. And then you do your research and you realize that there are strong correlations between diabetes and depression, between anxiety and heart diseases. But as a healthcare system, we don't address them holistically. So there's a way of when I say, well, there's an opportunity to do that.

And the third, what frustrates people in the industry is healthcare expenditures going up at double digit rates every single year, but yet more people are getting sick. So something is not right, right. Like if you have to keep paying more for healthcare, but yet more people are getting sick. The reason for that is because it's based on activities, you're paying for a consultation you're paying for a prescription or even digital health, your pain to track your steps up, count your sleep, or eat your calories, those activities, but they don't necessarily translate into actual health improvements. So we were like, imagine if we could figure out a way to change the economics to one where you're paid on success, only if someone gets healthy.

And so that was why when we not only just look at the problem at very high level of like, okay, well, a lot of Malaysians are unhealthy, but what specifically are the challenges? Why today's industry players are not addressing it? It's a bit like, okay. A lot of people want to go to Australia or London for holiday, but why is it that many people can't.

What about Emirates and Singapore airlines and Cathay Pacific that excludes this big segment. Similarly to entertainment, right? What is it about, today's satellite and cable companies that excludes millions and millions of people who don't have a hundred a month for a subscription. So same thing with healthcare at once you define the problem, then you can start to look at it in ways very differently from these big companies.

Ling Yah: And you don't only break down the silo. You also ensure it's very localized. How important is that?

Very important,

Azran Osman-Rani: right, because you know just like we talked about football, right? English, premier league versus local Malaysian football, the same thing, right? I mean, in California, when it comes to health, all yoga, Fitbit, meditation, kale, quinoa, chia seeds, right?