Powered by RedCircle

Listen at: Spotify | Apple Podcast | YouTube | Stitcher | RadioPublic

Welcome to Episode 50.1!

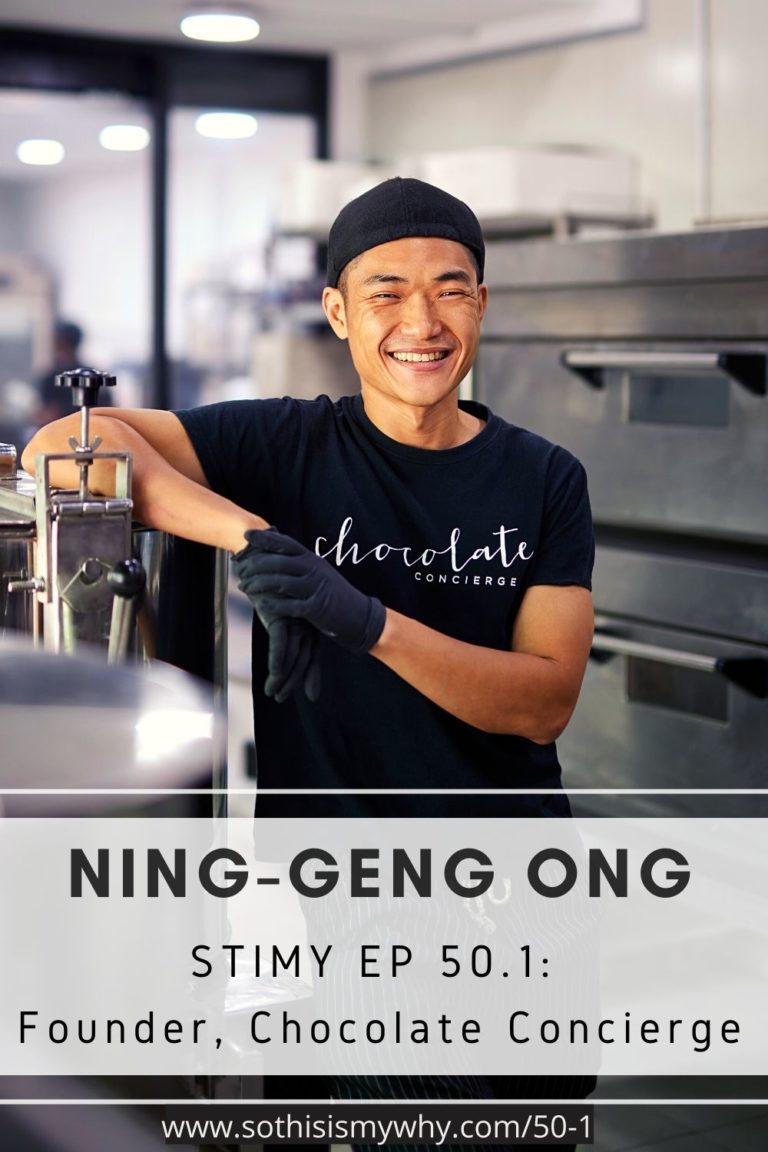

Our guest for STIMY Episode 50 Part 1 is Ning-Geng Ong.

Ning-Geng Ong is a farmer, chocolate marker, flavour fanatic and founder of Chocolate Concierge & Culture Cacao, where he makes incredible single-origin Malaysian chocolate.

In this STIMY episode, Ning shares his journey from majoring in physics and computer science, to founding a business in chocolate making. Everything from working with the indigenous community (including stories involving tigers, a durian thief and a murder!) and how he creates unique flavoured chocolates like assam laksa and nasi kerabu.

This is Part 1 of Episode 50. To listen to Part 2, CLICK HERE.

PS:

Want to learn about new guests & more fun and inspirational figures/initiatives happening around the world? AND get an exclusive behind-the-scenes copy of the research notes I prepared for each STIMY interview (including things we didn’t cover in the released episode!)?

Then use the form below to sign up for STIMY’s weekly newsletter!

You don’t want to miss out!!

Who is Ning-Geng Ong?

Ning grew up in Kuala Lumpur and loved the outdoors. He then went to study at Lewis University in Illinois, where he did a number of things including being an application developer, web design consultant and taught 3D design at the university in Illinois.

- 2:31: Loving the outdoors (the dangers of being a boy scout!)

- 5:52: Backpacking in Europe

- 6:59: Doing programming work

Ning’s Chocolate Making Journey

Ning shares how while he was working at his family’s business, he began dabbling further in the world of fermentation. And why chocolate in particular stood out!

- 11:53: Diving into the world of fermentation

- 17:37: Why chocolate making stood out

- 21:39: Cocoa seeds taste like.. Unicorn milk?!

Going deep into Chocolate Making

Ning shares how he deep-dived into the magical world of chocolate making, and why he created his own universe to combat his struggles in finding a reliable source of good quality cocoa beans.

- 24:26: Obsessing over creating Malaysian single origin flavour

- 25:08: Chocolate-making process

- 26:33: Creating the universe

- 27:08: Why Ning struggled to find reliable cocoa beans

Working with the Indigenous Communities in Malaysia

One of the most incredible things Ning does is that he involves the indigenous community in his chocolate making process.

He shares how that happened, his experiences in living with them, and the unique business arrangement he struck with them.

- 30:13: Starting Culture Cacao

- 32:11: Living with the Semai community

- 38:38: Tigers

- 40:15: Durian thief!

- 44:17: Not having a contractual arrangement with the indigenous community

- 49:08: Struggling to get cocoa beans from the indigenous community

- 50:52: Giving up?

If you’re looking for more inspirational stories, check out:

- Azran Osman-Rani: CEO of Naluri Hidup (formerly CEO of AirAsia X & iFlix)

- Guy Kawasaki: Chief Evangelist of Canva & Apple

- Oz Pearlman: Mentalist & Magician, Runner-up in Season 10 of America’s Got Talent & multiple ultra marathon champion

If you enjoyed this episode with Ning-Geng Ong you can:

- Tag us at @Chocconcierge + @sothisismywhy

- Tweet your thoughts & takeaways from the episode to Ling Yah here!

Leave a Review

If you enjoy listening to the podcast, we’d love for you to leave a review on iTunes / Apple Podcasts. The link works even if you aren’t on an iPhone. 😉

Send an Audio Message

I’d love to include more listener comments & thoughts into future STIMY episodes! If you have any thoughts to share, a person you’d like me to invite, or a question you’d like answered, send an audio file / voice note to [email protected]

External Links

Some of the things we talked about in this STIMY Episode can be found below:

- Chocolate Concierge: Website, Instagram, Facebook

- Subscribe to the STIMY Podcast for alerts on future episodes at Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Stitcher & RadioPublic

- Leave a review on what you thought of this episode HERE or the comment section of this post below

- Want to be a part of our exclusive private Facebook group & chat with our previous STIMY episode guests? CLICK HERE.

STIMY Ep 50.1: Ning-Geng Ong (Founder, Chocolate Concierge & Culture Cacao)

Ning-Geng Ong: When I found the first cocoa tree that I encountered was these low hanging fruit, because the fruit of the cocoa tree hung from its main trunk. So it was just two, three feet.

When I saw that food, I thought I was in Fairyland. Basically.

I thought, what is this thing? It looks like an oblong pumpkin. It has all these ridges. It looks like a papaya, but it's hard shell. And I thought that was my personal mysterious magic fruit discovery. so someone planted it, obviously. It's someone else's tree, but when I discovered it, I thought it was my own.

So I stole the damn fruit. I stole it as a kid. I didn't think twice. I stole it. I really didn't think it was someone else's right. I stole it and when I ate the contents of the fruit, it was just the most deeply edged memory I have of that age, because I thought this was my personal secret. That I've discovered something.

Ling Yah: Hey everyone. Welcome to episode 50 part one of the so this is my Why podcast.

I'm your host and producer, Ling Yah, and today's guest is Ning-Geng Ong.

Ning is a farmer, chocolate maker, flavor fanatic and founder of chocolate concierge and culture Cacao. Where he makes incredible single origin, Malaysian chocolate.

He's involved in the entire process from growing the cocoa trees he both owns and also from collaborations with indigenous communities like the Semai, Temuan and Temia. From harvesting and fermenting to processing, to making a wide range of uniquely flavored bon bons, chocolate bars, and brittles and barks.

But did she know. That Ning was originally a computer science major? And that there is in fact, a close relationship between coding and chocolate making.

In this episode with Ning, which is split into two parts, you'll hear about how Ning went from coding to chocolate making.

In particular, he shares his experiences living with indigenous communities to better understand them and their cocoa growing techniques. And it's a bit of a wild story involving tigers and a murder. So are you ready?

Let's go.

When you were a child, you were a boy scout and you loved the outdoors. Tell us a bit about that.

Ning-Geng Ong: I did love the outdoors and the boy scout years of my schooling days are probably the most parts of that period of my life and the friends that I've made during that time and the adventures and the dangers that we've had to find ourselves in and dig ourselves out of are still such great memories for me.

Ling Yah: You said danger. Was it actual danger?

Ning-Geng Ong: Learning knots and finding paw prints and taking expedition and cooking and building staff and furniture and putting up pens out of material that we find in nature.

I think we were in an island. That was maybe gosh, 14, 15 or 16. Someone in the troop was a good friend. And we went together with the troops. So maybe 40 of us in total.

We were in a night patrol so we would take turns to patrol the area that we are supposed to to keep watch. And in the dock I heard from a distant, frantic voices.

I found out that he was bitten by a snake and he was conscious, but not in a good state because to get to the island, we took a boat.

It wasn't some where we could just hop in the car and go to a clinic and his parents would notify. So that was kind of scary because knowing what I know now, the right cause of action would've been to hunt down that snake because if it was venomous, it would help create me to know which snake bit the poor guy and that would avoid him having to be administered the polybag Adam antidote rather than one that is more specific.

Ling Yah: It sounds like you were very independent as a child.

So were you also very much influenced by your family business? I believe he was a bakery supply as well.

Ning-Geng Ong: The business started when I was four years old, which meant I was too young to have known the intricacies of how that got set up.

Ling Yah: But you got to taste imported chocolate.

Ning-Geng Ong: At a very young age. Yes. And thanks to the family business. Very grateful, super grateful for that.

Ling Yah: Do you feel that seeing the fact that your family was running his own thing, that spark an interest in perhaps running your own business in the future?

Because when you were a levels, I noticed that you were the President of Entrepreneurs Club.

Ning-Geng Ong: It's funny you mentioned that because I didn't really hustle during A levels. The intention has been there to do something rather than not. in levels was really a short time actually at the Taylor's was a year and a half.

So the whole thing passed by with too many priorities, trying to do well. I'm trying to make friends. And then before that had any chance to develop, then people were already moving into their unis.

So after A levels, I backpacked for a couple months. And that's what led me to applying to universities in the states, which originally was not the plan.

Ling Yah: So what was the revelation and what led you to decide you wanted to apply to study at Illinois in physics and computer science?

Ning-Geng Ong: I was backpacking in France, Switzerland, Italy, and then the UK.

Some of my friends have already started their semester. So that allowed me to visit the campus at the university of Nottingham. And what I observed was that there were many Asian students and they were numerous Malaysian students.

I thought, okay, you know, this doesn't socially seem too different than the levels and what I've experienced before. And the program was scheduled in such a way. As I understood at the time, that there were very little room or students hardly took the opportunity to take classes that were outside of the program.

And I thought, okay, If I can, I would like to be in a position in uni to take classes that were interesting to me rather than just to fulfill a program requirement. And so I thought, okay, I'm going to move somewhere else. And that's when I applied to American universities.

Ling Yah: So you must have really enjoy what you were doing because for quite a while you were doing a lot of programming work as well. You were doing web design consulting, you were teaching 3d an application developer. So you must have really enjoyed that side of things.

Ning-Geng Ong: In fact, I did.

That part of my life, where he taught me many things that I still use as a model when I'm running my own business.

Now for one, I had two amazing bosses because before I graduated, I was a student. employee slash intern for both the marketing department. We had a application developer development division under and also instructional technology.

When I graduated, the two departments decided to create a position to hire me under, and so that allowed me to work on the two separate bosses and two women bosses that they were till today.

I still look back and use the interactions I've learned then as, as a model to how I want to behave as a supervisor, as a manager, as a boss. No number one time was the director of marketing Susan, Sally was the director of instructional technology and Mona always be foot to everyone on the team as her colleague.

I've always felt that we were a team, and that just allowed me to pour my heart into whatever I was doing. I mean, granted, I was young. I was probably not every day, the most motivated employee, but when I think back of my time there. I only have fondness and Susan just allowed me a lot of freedom to decide how to pursue certain objectives. when I ended my stay in Illinois, at the time I stayed between I was working in this town called remove view.

When I tell people this, they say, how is that such a town town is Romeo Gill and the next town is Joby yet not making this up. That's spelled J O L I E T. So it's Romeo and Juliet. So I spent close to 10 years there and immediately I can remember about 66, 55. so my mind map is still there.

And when I came back to Malaysia, I started off with this idea of idea, rather of how workplace interaction, communication, hierarchy expectations are, which made me walk into walls a lot of times, because I wasn't in a workplace with Western culture to Asian, but then it's the worst kind of Asian business to work in, which is a family business and it's my family's business.

I think I went from one spectrum in terms of how things ran to the complete opposite of how things rent in a sense that there were a lot of ideas that the people on the ground would not expect it to have. In fact, the expectation was that they do what they're told rather than to come up with their own ways.

Which didn't sit very well with me. And I'm trying to until today be cognizant of the fact that if I hand off a project so it's something that I'm aware.

It's something that I want to empower the team to have, although it may not be innately expected of an organization when they are working here. To empower them to decide the minor things, but hold them accountable to the final results.

Another thing that was quite a cultural contrast was just ideas. I felt that when. Subordinates were asked in a meeting to brainstorm people just shut down. they're not really expressing their thoughts. And I think some of the reason for that is because a lot of times they feel that their ideas will not go anywhere will not go far.

So they're not willing to invest in that.

Also, I think there is this schooling that has not encouraged that as well for anyone to speak up.

During my time I was in a class of 50 something students.

So the teacher can't really have the time to go through each one of them and say, how do you feel about this? You know, what are your thoughts about this? And so on. And it's pretty much classroom management. And by the way, have a strong fist. Do as I say, or else.

And that after years, I think has an impact on how people then behave when they are made to think, and to respond rather than have information just given to the men and expect instructions to be given and handed.

And for them just to execute.

Ling Yah: Clearly, you know the culture was so different from what you were expecting and used to the states. And I wonder because of that, that you felt that maybe you wanted to do something of your own, then you start started exploring and trying to say, make your own needs or, beer or cheese.

Is that what sets you off on that path?

Ning-Geng Ong: I find tremendous fulfillment in going deep into something. So fermentation was something that I thought, wow, it's fascinating.

Fermentation has parallels programming. Fermentation is when micro organisms, either yeast, bacteria, or mold, add on an ingredient and transform it through metabolic processes.

And you have an output that is very different. Transformed due to the process of implementation and pay smell. I have the texture. That's very different from this starting point. And I look at these macro organisms as robots.

In programming, we have bots. What we do is we set the initial variables, okay?

B equals whatever, run for how many loop or when certain conditions are met, then that's when you exit the booth or you tell me no, you move to the next phase and so on and so forth. And I look at fermentation as being that. If you set the conditions correctly, it's repeatable. It's work that's done by microorganisms, which meant that you could just leave it and come back to it.

and the thing is transformed. Be it honey to mead, or unfermented cocoa beans to something that's closer to chocolate, not quite yet chocolate, but somewhere there. So I'd been to myrin or soy sauce or Tempe. So really exciting idea.

The more I found out, the more I realized that a lot of the fruits that we enjoy go through some form of antiemetic transformation or fermentation. Coffees, teas, wines, beer, for sure.

And chocolate.

And when I wanted to do something and totally geek out, I thought off, Hey, chocolate is one thing that unified a lot of my lives interest and consolidate it, but I thought I could be

spending my time in a meaningful way and also a way to contribute somehow. At the time when I started, because of the family business, being available at a time for me to taste the different chocolates that were made from different countries out of beams that were grown out of different countries, it really set a stage for me to to build on.

And I took it initially as just the side project very early on. I made chocolate out of the home kitchen, just as one would start say a home brewery or a microbrewery, because at the time internet was booming with a lot of information about home brewing and at the same time chocolate making.

There were a number of forums.

Two that comes to mind are John Danse's chocolate alchemy and this chocolate life from Play Garden. So these two places provided a lot of information enough for me to pursue chocolate making with tools that were an equipment that were inexpensive readily available. And just allow me to start by having an access to beans because at the time being interested in things like coffee and teas an understanding what the impact of region terrior and origin has on flavour.

Since Malaysia has a lot of growing conditions that are favorable to cocoa we have a number of trees that were planted around the kitchen that made chocolate that produced the beans that allowed me to experiment in a very, very small way. Just. Under two kilos worth at a time.

And to make that chocolate in a very crude way.

At the time when I made that first batch of chocolate and I thought, wow, this chocolate is amazing. It's made so crudely, but this whole time I've always thought of chocolate as a bread box. You buy it in a bar, you peel open the wrapper, no idea how it got onto the shelves.

What kind of process the cocoa beans need to go through in order to end up as being a chocolate?

So when I first experienced that transformation, I was simply blown away. Then I realized that this is the experience of almost 500 to a thousand other chocolate makers around the world.

They make a chocolate really crudely. They take a bite and realize, man, this is the, next best thing in the world. And then they're egged on by the friends and family and say, Hey, you know, this chart, your chocolate is great. Why don't you go into business?

Years in, the chocolate making pot is that easiest thing to get, right?

You really can't fudge it up. The hard part is running it as a business.

The hard part is the H R, is the accounts it's taxes, finance, hiring business, license, food, safety, sourcing, purchasing accounts, payable, delivery, logistics. This is the other stuff that they don't sit. people who retaliate he, it's a great idea to start a business. They don't tell you look out for this.

Whatever you want to sell, right? if you're selling donuts, you make a donut. That's how you make a salad, a loaf of sourdough bread at home. And your friends and family are nothing but supportive.

Like this is best sourdough bread, but they don't tell you when you go into business. Hey, 101 things, you know, that death from a thousand paper cuts.

You have a great product, but that's not what a successful business can depend on solely. you have a successful product, then there's this thousand other pieces of puzzle that needs to fall into place before it can get somewhere.

Ling Yah: Before reality set in and you were oh my gosh, this is magical and amazing. Was it that first batch that allow you to decide that chocolate is what I wanted to do? Because as you said, you really deep dive into what you're exploring. you went and got a certificate with a sommelier, you really deep dive with so many different things like beer and coffee.

So what allowed chocolate to really, really stand out from everything else you're pursuing?

Ning-Geng Ong: I've always enjoyed the experience of things. The experience of understanding something in depth, the experience of having contact with colors, flavors, textures, taste, and I'm curious in that way.

So you're right. I did take a introductory level to the courts of sommelier, which is a wine professional certificate.

And I'm not from that industry, but having gone through that deepened my appreciation for what a glass or bottle holds. And part of that process was to blind taste a series of whites, a series of reds and call out the vintage to within a year. Make a guess on to the variety, the region.

And I thought, how is this even possible? it's not a multiple choice question. The possibility piece are endless.

But later on, I appreciated that if you follow a certain method you could come to a pretty good guess and I've taken that idea to other foods and beverages, teas, and coffees. Green teas. Matcha, which I'm starting to find an appreciation for and also chocolate.

And it's this, contact of when the rest of the taste receptors hit. Whatever I'm trying to taste the chocolate. That's when the magic takes place. this is what all the work that has been done before a bar chocolate becomes a bar of chocolate. This is where it shines. This is where it shows.

You can tell the biggest story. But when they say when the rubber hits the road, if it doesn't deliver, then the most wonderful story is just going to fall flat.

For me, chocolate was important and significant because first, it can grow in Malaysia. And for me, that tied with my appreciation for nature, for things that can grow the trees, the plants.

Something that fruits and flour, something that has grown from the year. And then I thought particularly interesting because I recall when I was a kid living in Subang Jaya, SS 14 at the time. And no one, nowadays, believe me, when I said that Subang Jaya had a large swath of palm oil estate.

And it's like, no way, you know, do you mean like further down in Shanghai? I said, no, no, no, no, Subang Jaya. SS 14. Across the monsoon. It was like just palm oil estate.

And I remember this very vivid, so I was quite a lonesome kid, latchkey kid, and I would take strolls in the Pomona state alone. Don't recommend this for kids, by the way, don't do this.

Don't do as I did, kids.

When I found the first cocoa tree that I encountered was these low hanging fruit, because the fruit of the cocoa tree hung from its main trunk. So it was just two, three feet.

When I saw that food, I thought I was in Fairyland. Basically.

I thought, what is this thing? It looks like aan oblong pumpkin. It has all these ridges. It looks like a papaya, but it's hard shell. And I thought that was my personal mysterious magic fruit discovery. so someone planted it, obviously. It's someone else's tree, but when I discovered it, I thought it was my own.

So I stole the damn fruit. I stole it as a kid. I didn't think twice. I stole it. I really didn't think it was someone else's right. I stole it and when I ate the contents of the fruit, it was just the most deeply edged memory I have of that age, because I thought this was my personal secret. That I've discovered something. Obviously later on when I showed my friends the fruit tree they're like, oh yeah, this is Coco.

You know, someone else planted it, there's another one that's down there and all that on that. Oh, okay. Okay. So it's not such a big deal after a bite. For me though at the big deal. So I've kept this memory of my first contact of the cocoa. And I think it was special for me.

Ling Yah: I read that taste that you're talking about.

It's like a cross between soursoup and mangosteen, right?

Ning-Geng Ong: It's soursop, mangosteen, L to be honest, unicorn milk.

I think it was more significant for me because it was my personal discovery. No one showed it to me and I chanced upon it. You know, when you're reading a novel, you place and time that is so mysterious or magical, and that's how it was for me.

But also at the time, when I jumped in deep into chocolate, I thought that it was just a weird that, of all the chocolate origins that I've tasted Costa Rica, that Venezuela and the Madagascan Dorian benign. In Malaysia, the logical question was where's the Malaysian origin.

And at a time when I was asking this question, I couldn't find anyone who was making it.

I made calls to a number of chocolate makers. Nothing.

The dialogue usually was hi, I'm looking to buy some dark chocolate. Do you make 10 supply chocolate? Yes. Okay. Are you making these chocolate in Malaysia? Yes. Oh, fantastic. Do you know the origins of where these ingredients that you're using to make the chocolate but where are they grown?

Yes, we do know. Well, is it Malaysian? Some of it, but not all of it's it. And then I'm like, okay, do you have a product that's a hundred percent Malaysian. And it's usually at this point, you get a resounding. No.

So later on I found out why, because a lot of the chocolate makers don't start from the beans. They start from liquor. It's already grounded up at the place of origin. Usually Africa, that supplies 75% of the world's cocoa. And if they use Malaysian beans, it's usually a brand because the supply wasn't a lot. A lot of beans were still coming from Indonesia. So Indonesian beans were invariably used because of assessability pricing.

And so to scratch that itch, having just been through Somalia cos and understood how coffee tastes like, you know, from Kenya to Papua New Guinea to Panama. Like I must haze a Malaysia and to scratch that itch, I learned how to make chocolate to personally scratch that itch. that was the first step into that rabbit hole.

Ling Yah: To set the context a little bit for those who don't know back in 1990s, Malaysia is actually one of the top three in the world who produce cocoa.

Ning-Geng Ong: In terms of volume and then it just fell off the scale. It's like from a hundred percent now we have less than 99 point something percent of the, growth has just been converted to something else, mostly Palm.

But in the case of Pahang, it's now durian. Mostly all these places that we're planting. Now, it's making a killing. We wind that 25 years ago, all of that was Coco. for such a state like pre-hung it was having so much poker that rivaled east Malaysia.

Ling Yah: So that obsession with taste that you said, is that why I'm going to assume that right from the very start you were obsessed with creating this single origin flavor that you're so known for.

Ning-Geng Ong: The session more out of a curiosity. I just wanted to experience it. If it's good, if it's bad, I just want it to know firsthand but no one could tell me how it was. textbook answer is Malaysian cocoa chocolate is sour or it's acrid or it's not good, but when pressed like, okay, fine.

give me it. And I will form my own opinion on it. No one could produce the bar. That's how heitgot started. Hey, come on. Someone give me a damn Malaysian bar and since no one could then, okay, roll up my sleeves and how hard could it be to make a bowl of chocolate.

Ling Yah: So you roll up your sleeve. Can you give us a cliff note version of what the process is for creating that shock? And then we can deep dive into each of those stages.

Ning-Geng Ong: Basically you have cocoa beans that are fermented and dried.

That's your starting point. Okay. If you don't own a farm, you get cocoa beans that are fermented and try at the farm. Once you have that, it's roasted. Once it's roasted, it's like a peanut shell. You grind the contents of the cocoa beans, which we call nibs.

If you want sugar, you actually, if you want maybe vanilla, I don't use that or no powder to make milk chocolate you add that in.

And at that point, it's just a matter of refining it to a particular size that is not detectable on the human palate. once you do that, you can use a pestle and mortar, if you have the time and the energy, if not, you automate that. You can get pretty far with the blender, but not all the way to what we would consider conventionally as a chocolate.

But the flavours are there. If you just put sugar and roasted cocoa beans into a blender and just blend it together, you get the idea of the chocolate without necessarily the texture that's it just two ingredients.

I'll give you the recipe, you know, 30% sugar, 70% cocoa nibs in a blender you have. That makes us 70% dark chocolate.

Forget about tempering. Forget about moulding. Just pour that into a shallow plate, sticking to the fridge when it solidifies that's chocolate, guys.

Ling Yah: You often joke about how, if you want to meet anything from scratch, you start with creating the universe.

Ning-Geng Ong: Yeah, that's a Karl Sagan joke. A lot of times, I chuckle when another artisanal maker say make, their soya sauce or tempeh or taufufah from scratch. what do you mean by, from scratch guys? I mean, are you planting?

Are you planting your. soybeans, are you doing that? Are you breeding the genetics that goes into that? Or if you want to start from the very beginning, it's the start of the universe. that's when things started to as we know it, fall into place.

Ling Yah: One of the very first things that you were struggling with, as I understand, was finding good, reliable cocoa beans, and you were struggling for six years to find this. Why was it so difficult?

Ning-Geng Ong: This is where I'm going to borrow again from my computer science background. Data scientists know this. Garbage in garbage out.

So to begin with the best possible ingredient is important. If you want to express the full potential. All of this sits in flavor that is present in the bees and for a long time, that was a problem for me when I wanted to make more chocolate. Basically I just wanted to make more than the 10 trees could afford me in terms of how many fruits or beans that I c ould harvest out of 10 trees.

The challenge then was to get a reliable supply and to solve that problem later on, I found out it was a great idea. So to solve that problem, I enrolled myself in a Kursus Asas Penanaman Cocoa, which is a cocoa board. Basic introductory course to cocoa planting or cocoa plantation.

I was there with a notepad and a pen and I was the networking guy there. I was there just to take down names, phone numbers, and then call these farmers out because I wanted to see.

If I could visit their corporate farm and get my hands on more cocoa beans. So that was my initial intention, which I successfully did.

After the course, I called up the number of these farmers. And I say, I'd like to see your prop. And I went out there. Wow, beautiful trees. Going great.

And when they presented me with the beans, a lot of them were not fermented or were not correctly fermented because the beans in Malaysia are bought by middlemen who really didn't care much about the flavor or they roll off the beans. And so the farmers would not incentivize to pay more attention since they're not incentivized to do that.

So whatever that they were fermenting worked.

If it smells great, great. If it doesn't, if it smells bad, who cares? It still catches the same monolith per kilo. But when I did find the farmers that were fermenting it at the time for me was, did a pretty good job. So I got a sample, but when I placed an order, I was horrified to find that the sample, which I impounded at the farm did not match in terms of characteristic or property to the order when it was fulfilled.

And after having experienced two or three of these failures. Meaning, I got a sample that was great. And then when I ordered it, I got something totally different. I wised up and I thought, okay, if I wanted to make more chocolate at a time, it was still a side hustle. I just wanted to make more basically I needed to be able to control the fermentation and that meant I would need access to an area that I could process cocoa beans.

And that's when I started to look for a way to do that, which meant at the time buying into a farm in in Pahang, which was close to a number of areas that we're still growing cocoa.

Ling Yah: Is this the one way you end up partnering with and with Kong Weng and as well. Cause I thought it was very intriguing that you would start culture cacau, it has a very kind vision vision in a sense that you want to give back to society, which is very different from someone who, if I have a side hustle, I want to make money.

I'm going to focus just on profits, but you were clearly thinking of a bigger picture then. And I wonder what was driving all that.

Ning-Geng Ong: Yeah. So I met Weng and subsequently Kevin because they have a plot in Pahang and they had cocoa on the plot. So when we met, I said, I'm looking for a plot, preferably with cocoa already growing on it.

And probably somewhere I could ferment and dry beans. things just came together is someone who clued me in. Who sparked my interest in giving back to the community.

So he's a community leader is involved in a orang asli boarding school that is situated minutes away from our farm. It's Semua, in just north of trust between Bentong and Raub.

it became something that was natural and a way for the initiative to be more than just a business.

We felt it wasn't one way at all. To have this perspective of wanting to take care of the community and environment just vaccinate that with the three of us at the farm level, and this later on translated into chocolate concierge Also interested to pursue an environmental cost and a community cause and wanting to formulate that into the core of the business.

So that as the business grew, so would our contribution into these two areas.

Ling Yah: What I love is that when you are interested in something, you really go in depth and you weren't just coming in and saying, I'm going to help these orang asli. You really tried to understand where they're coming from.

You spent a week with them just to see how they were harvesting. What were some of the main takeaways that you have from just spending time with? I think the Semai in Changmai, right?

Ning-Geng Ong: Yeah, it's the Semai community.

Initially was such a cool idea that I thought okay, I'm going to spend a week with these guys.

What also drove me to do that was when I saw these cocoa beans coming out from the Semai settlement and I thought, wow, how are these guys able to grow cocoa without any pesticides as they told me. And year after year, the pesticide report comes back with no pesticides residual detected. None detected.

So this confirms that they aren't using any pesticides. And I share these with the farmers that I before met. I said, Hey guys, do you know that the orang asli are farming cocoa and they're successful. They can get a yield without using pesticides.

It's like, they won't believe me. It's like the boy who called the emperor naked.

And the response I got was varied, but was more like, Hey, you know they're spraying when you leave or another farmer told me that oh they're starting fires at the perimeter of the area. All of these are just fantastical imagination because the orang asli are so minimalistic in their farming approach, they're very efficient with their time. So they spend very little time to get a lot done.

And so they're not spraying. There is no agriculture pesticides start that is within traveling distance from the village, which is an hour and a half in from the main road. and if they have money, they're not going to spend it on that. We know that, and they're not starting fires because it's often one guy running an area that is two, three acres.

And If it's an evening thing, he's not going to go around and stocking fire. that's just not realistic.

So I wanted to find out firsthand, how are they able to do that? So that was one of my very important mission to understand how is this even possible? So I started a chat, at least at a time, I thought, okay, I'm going to go visit.

So each household has two to three acres that they manage, which the community I lived with had mangosteen, petai, betel They had Jack jackfruit vegetables, and a lot of it was semi wild. it wasn't complicated. It was just whatever that grew.

I drew up a list of factors that I wanted to check what was allowing Coco to grow in a way that is successful yet pesticide-free.

So one I looked at, was it the altitude? Was it the soil nutrition? Was it the genetics of the cocoa. Was it whatever they were co-planting with? In other words, what's the biodiversity around the area.

Was it their farm management system where they pruning excessively? Are they clearing the land? What's the planting distance and so on. So I pretty much checked each one of them and came down to the realization that it was.

Only bio-diversity that was the factor that allowed cocoa to grow without pesticides. And when I discovered that for myself then it became obvious later on that when I'm reading about other crops as well, they're are doing very well when it's not just a mono crop or monoculture, when there's ininter cropping.

The pest pressures were relieved or lowered and fruit forest and, and start learning about permaculture food, forest, and agroforestry, then examples of people having succeeded in, one way or another across different continents allowed me to have this realization that I would like to pursue this in the plot that I'm managing.

This realization really started when I spent a week with the settlement. And my host was Abu. there was no TV at a time. There was no cell phone data.

So at night after dinner, he hosted me. Before I went in and I had to get the agreement of the village chief the batin. So I asked hey, you know, do I have the permission to come and spend a week? And he thought, okay. Yeah. So Abu is my uncle, they'll host you and you, his wife will cook and can sleep in this area.

And I was like, sweet. So I came back, two weeks later and met Abu. And when I came in, I brought the chicken. I brought things that I thought would be my contribution towards the meal that didn't last the whole week, but we ate whatever that we could within the first two days. And then after that was where it got interesting.

So when we exhausted the chicken, that's when the meals became really interesting. So in our morning walks out there, you know, what do you want? It's like okay? What's on the menu? And I learned a number of words in the Semai language.

So come here, is chek matik. Chek Matik. some words seem very familiar because it's got like either Hokkien or Malay sounding words that similar, like eat together. It's Chuck summer, Chuck summer. So it's not unfamiliar, but familiar. And so in the morning we discuss, okay, would we cook?

And Abu is the one who would cook together. This is five. So in the morning we that, okay, let's, get some taro shoots and then he would go to the river and he would pluck some tumeric. We would have a lot of these vegetables but always rice. They love their teas too sweet. So I don't drink the teas.

But the rest of it is just fantastic. Just these different herbs that I would never otherwise have experienced. And later on, I had to find out what the Malay was for each one of these. Semomok in Semai language was semomong.

When I came on and put a shout out, say, half your experience, like what?

Then I realized that I'm going to send a photo and they do realize, oh, in Malay it's semomok. Then people could understand what I was talking about. There's a lot of lamb and a lot of highly seasonal, but super interesting. So in the morning we would walk the area and he would just slash and was probably by his dog. And then I would follow behind the doc.

So the trio, a lot of times the dealt with sometimes need fall back behind our boot, but I will always be the last one. So doing that for a number of dates, a lot me to better understand how it was managed and how it was possible. It also gave me a glimpse into what life was truly outside the city.

And although all consider ourselves Asian or Asian culture, that couldn't be further away from home. In terms of how they view possession, what is their relationship to each other? Because in the supplement that all relate to in one way or another. And also the tremendous stories that I thought really should be going into a book.

So in his lifetime, has killed two tigers.

Ling Yah: Wow.

Ning-Geng Ong: With traps. So he goes into the jungle and he set a number of traps and these traps would get whatever comes in that way. he taught me how to set such a trap. I mean, he wouldn't even teaches his second son because it's a real serious trap, but he taught me. He showed me how to set a trap.

The amount of force that you can put into such a trek. It's spring loaded by three branches that are two inches thick, at least. And it would be loaded. It takes an adult to look one to spring one brunch, but that would be three and such a spring if sprung.

I mean, it's such a trap would cue an elephant if an elephant went into it. It would just die on the spot because there's no way these spikes go through. They would break bones. So they won't go anywhere. The trap is from the animal will be there.

So not by choice, but he has killed two tigers and he's lamenting to me because now that he knows the price of a tiger, what a tag that should be in the hundreds of thousands, know every part of the tiger by the time the road wasn't accessible and the villages brought the tagger back into the village and ate it. They ate it like any other meat.

So the whole village had tiger meat.

But to just listen to stories like that, and it's a very different life they live. He has seven surviving children, but he'd stopped at the Dodson and some of them didn't make it But it's just his attitude of accepting the hand that life has dealt him.

And another experience that I thought was valuable to me was. So there was some, one that he's been warning me about in the village because he's known to be a thief. Stealing from others. And it was during durian season and I have timed my stay to coincide with the durian season. I mean, purposeful, because I was after, you know, these fantastic, fresh durian that's not from the farm.

And so we know that this certain individual would see other people's do and then sell it as though it's his own.

And such a morning, we saw this individual coming from the direction of Abu's land. And soAbu with his parang behind his back. He did, the guys are how you are, what you doing? How are you doing? How are things? And it's like, oh, not being all this good. And him carrying two hand, handful of deer. Right. it doesn't get more red-handed than that.

But anyway, he just answers like, doesn't skip a beat. He's just answering. Like, oh yeah, like it's all right. You know, this and that. And I was like, what are you doing here? And the guy's like, oh, I saw two rats and I chased it. And they led me to your lens and. They ran away and now I'm, leaving and he walks, away with the, dude I'm witnessing this with utter disbelief.

And after the guy left, I tapped Abu on the shoulder. I said Abu, you know, those are your durian, right. And Abu was like, yeah those are my durian.

And I said, well, what'd you going to do anything? And to this day, how you answered me with stay with me, it's like, yes, those were my direction, but he needed the mall. And I still have trees that will give me more direction maybe today, tomorrow and beyond.

So it's okay if he gets the five, six, five, or six fruits that we can carry with him because he needs them more. So that kind of one sentence wisdom and, just the forgiveness is something that to this day it's a model that I can't yet live up to that forgiveness is just because our sense of possession is so black and white.

What's mine, what's yours and it's drawn so clearly. I think it's very humbling that just so happens that the trees grew on my land doesn't mean that the fruits contribution. And I think actually learning that lesson, I'm very hung up on forgiveness.

I don't think it comes naturally to me. I'm one where I do remember everyone who's crossed me and, to observe the opposite, but it's this and that because he might be very forgiving in this, but then he's petty. The Semai culture is one where they can be very petty as well. So it's not something that can be summarized with just saying that, oh, they have this folk wisdom that, we must learn from.

For example, if I came in with a donation of rice or clothes. I must be very careful to both give it to Abu because he was my host, but also to the batin, because it's the batin. If I missed any one, then that would be very bad blood. That'd be politics.

There was one time I paid the Bakhtin to cater to a group of visitors who were interested in learning about cocoa , and how agroforestry with cocoa looked like.

So I paid a small sum and then. He got in trouble with his uncle which is Abu, because Abu thought that he kept most of the money to himself and didn't spread it to the village. But I paid him for the meal that he catered to me. I had to clarify with, I would say I only paid him a certain amount and this was sort of food.

But to have to, navigate through that is a lesson that is valuable when I'm continuously growing a relationship with the RMST, who we work with to go to cocoa that we transport to our farm, ferment dry, and it's making it to the chocolate.

And we credit the orang asli for the chocolate that is made from their cocoa. If we're working with three communities. If it's the Semai, the chocolate will be called the first word of it will be Semai. Not dark chocolate or hundred percent, whatever the first word have. It would be somebody to credit the community.

Who's growing it. Then the other two communities are the Temuan, and Temia.

Ling Yah: I love the fact that, you know, there are people who live by such different values and cultures and expectations, and it sounds very much like they're very self-sufficient so going in and experiencing, seeing their lives, how do you feel that you could contribute because you ended up deciding to give them like bananas and organic fertilizers, right.

For free to help them. So how do you decide, you know, how to start that because you don't have any contract with them as well, which is a very unusual, arrangement to come to.

Ning-Geng Ong: from the start. It was out of sheer Goodwill to not want them to feel in any way that they can only supply us.

If the bananas go to maturity and we actually give out more banana trees than Coco in our assistant program. So we really did want to help but there were a lot of lessons learned with regard to that. For example if we just gave trees, it's just too many trees and they can't plant it in time, they would just let the trees wither.

So later on we learned that lesson. So rather than just giving trees, I would then organize volunteer planting programs. So we would go in, we would give the trees by and we'll also have them planted. So all the trees would be planted in the ground and we'll have a better chance at surviving into adulthood.

So that's just something that we tweaked because week after week, we went to the village, like, what are you doing with all these trees that we've paid for these trees, you know. It didn't come free. It came from nursery and we\ spent hundreds of thousands in procuring these trees.

And. Well, they're just busy, you know what you're going to do. I'm busy, you know. They have a household to provide and they have short term or seasonal work, the patriarchs. So they're doing plantation work, construction work or some other work. And so they don't have the time to plant the trees. later on, he realized that, yeah, rather than, you know, just giving the trees wasn't good enough.

We had to ensure that they are planted as well.

Ling Yah: So after they have planted and they've harvested, I believe that's when you come in and you pay three times the market value to have those kinds of cocoa pots.

Ning-Geng Ong: In the beginning, the, Price for the wet cocoa beans.

When I say wet.

So this has to be, not that it's unfermented and fresh, the price that was published and on offer by the, middleman was 60 cents a kilo. On the first day we paid two 50. So we went from the market rate at 60 cents to two 50 and now it's improved. Now it's up to three ringgit . We'll be increasing to three 50 because we operate from a very different model in that we weren't just going to pay 5 cents more order to secure the supply. We wanted a price whereby. Why two 50 was because the dried beans were offered to be purchased by the party at around RM 6. Under RM 7.

And the conversion was three to one or three times. Meaning if I started out with three kilos of fresh beans, wet unfermented beans, when it's dried, I would end up with one kilo. it meant if I paid two 50 for each of the wet beans, that one kilo of dried would have earned them seven 50.

And that distinction from day one was important for us to signal to them that had be fermented and dry their beans, they would have gotten a lower price. So if they did more work. They would have gotten a lower price.

So we wanted to immediately remove this hesitation, which was, I'm only getting X amount, but if I have time, I did more to it, I get a higher price.

When they're dealing with us, if they brought it all the way to dry, they would have gotten less.

But what I didn't think of was that that was not intuitive to them. They couldn't see that two 50 at unfermented and fresh was a better deal and was worth three times more when it was dry.

They couldn't see that. They couldn't visualize that conversion. And so what it took for them to get on board was basically we had to have the Lembaga Cocoa. Or someone they trust as an official, because it's a governmental body, which gives them a lot of assistance in the past.

Basically the Lembaga Cocoa had to show up at the village and look, these guys in the eyes and say, sell to Ning. Sell to this taukeh. Because he's giving you a price that is unbelievable. And no one else is paying you this price. If you sold it dry, you don't even get it at this price, sell it to him. And that was

I thought it was embarking on a certain direction, but reality was quite different. And I had to do a few of these in navigating. And another one was coming from this mindset of excellence, having visited the winery in Margaret River in France and looking at how they're growing their grapes, the vineyard. How well managed it is.

And I envisioned how Coco should be procure, you know, the kind of quality, you know, I thought absolutely triple A, flawless, great Coco.

So initially when I dealt with the first community, and that was the Temuans. I told them exactly what I was thinking. This Coco is not good enough because it's got mouldy beans in it.

These mouldy beans should have been separated, not being piled together with all the good ones. ones too old. These are to dry. These are half eaten. You should weed it out. So I basically told them the grid. I was willing to accept.

The next trip when I went in. No one wants it to sell to me.

So I knocked on the same doors and the guy comes out, opened, it, opens the window, looks at me with a big smile on the face. I said, what happened to the cocoa, right? You're not selling cocoa to me today. boss. I look around me. All these trees were laden with fruits, just hanging there, ripe, ready to be picked. I'm like, what about bees? You know, like back in front of your window, I mean, you can't hide it's obvious as day.

What about these fruits that did not boss

inspires my eyes. So I stepped on a few feet, the trip before, and I realized that the way forward was even if it wasn't the quality I wanted, if it's still salvageable, I would still pay them. And if it's really not salvageable, I would still pay them and then discard. And that was necessary for the relationship on that.

Everyone regardless of the quality of the beans had to be paid. And that was the cost of working with that community.

I had to adapt rather than insisting on doing things my way, when I was dealing with this community.

Ling Yah: Do you ever feel like you wanted to just say forget it. I mean, if you're being so difficult, I'm trying to help you and you don't want me to help ,you forget it. I'll just run my own farm because I have them anyway and then do it to the level of perfection that I want.

Ning-Geng Ong: No, that never crossed my mind there is another level of detachment, which is arms length.

At one time, I got so involved because I stayed with Abu and all that. I was getting roped into the villages politics. Village chief at the time was reported to have committed murder. And so that was an investigation into him because there was certain individual that was a missing person and he got really ugly.

And then he was expelled from the division, had to move up river I'm getting both sides of this story. And this is with the two government coming to quit, but they each had their own party. And I had to put a stop into that. I said, okay, look, I appreciate all that we've done, but you have to deal with these situation.

I mean, I got really involved at a time. I was buying medicine for different individuals, but it really is cheap. Every time I go in, I knew exactly, when his medicine would run out, but I had to instill an arms-length, which is, I'm not your mother.

This is a business transaction. I don't owe you anything more than the money I put into your hands and you don't owe me anything more than the cocoa that you deliver. So after a few times of this, I think it's now at a healthy distance. The relationship that I have with this specific company, but I had to extricate myself from that.

Ling Yah: And that was the end of part one of episode 50.

The show notes and transcript can be found at www.sothisismywhy.com/50-1.

Alongside a link to subscribe to this podcast, weekly newsletter. If you want to find out how the rest of Nick's journey goes, check back this Wednesday for part two.

We cover the process of making chocolate from beans that have been fermented for up to 71 days, how he creates uniquely flavored chocolate like assam laksa and nasi kerabu, advice for aspiring chocolate makers- honestly, anyone can do it at home.

And finally, the flavors he would recommend people ask from chocolate concierge.

Want to hear how Ning's story continues?

Check back this Wednesday for part two.