Powered by RedCircle

Listen at: Spotify | Apple Podcast | YouTube | Stitcher | RadioPublic

Welcome to Episode 41!

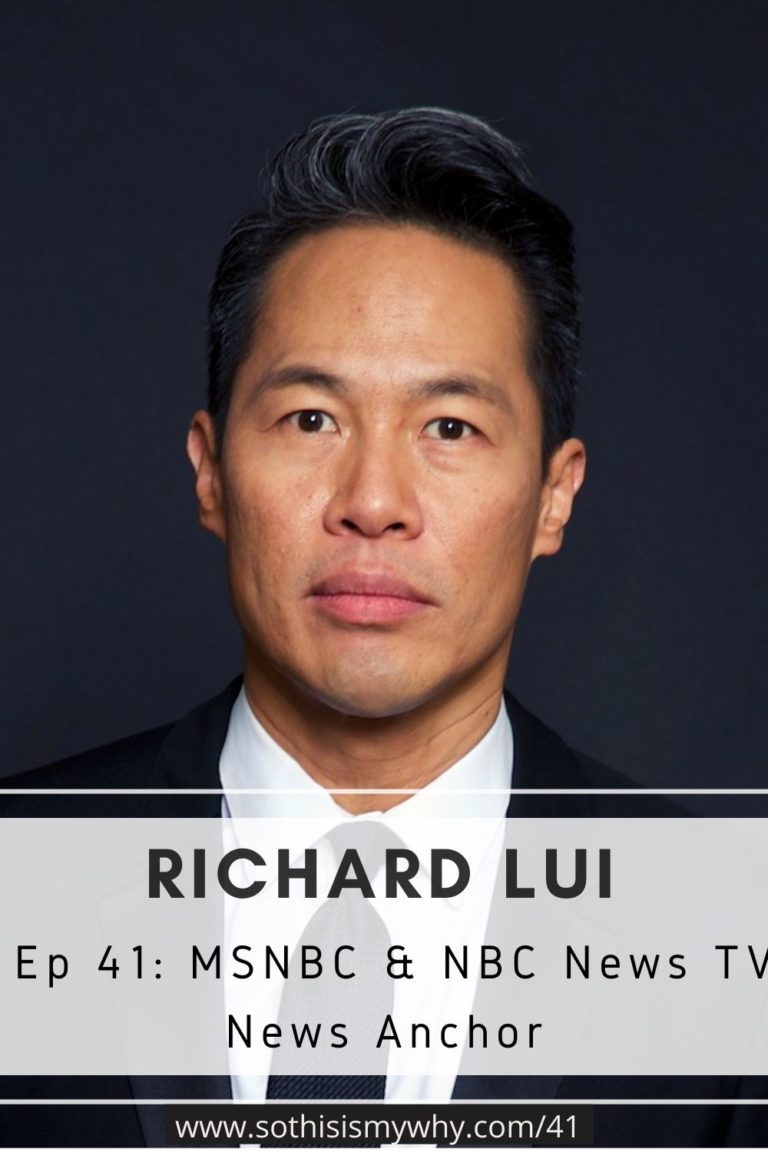

Our guest for STIMY Episode 41 is Richard Lui.

Richard Lui is a TV news anchor for MSNBC and NBC News and was previously at CNN Worldwide, where he became the first Asian American male to anchor a daily, national cable news show. He also earned the Peabody and Emmy awards for his team reporting at CNN during Hurricane Katrina and the Gulf Oil Spill. Mediaite ranked Richard among the top 100 in news buzz on its “Power Grid Influence Index of TV Anchors and Hosts” & was also listed by Business Insider as one of 21 dynamic careers to watch alongside Warren Buffett and Mark Cuban.

In addition, Richard is also a columnist for USA Today, Politico, The Seattle Times, Detroit Free Press and San Francisco Chronicles.

Prior to journalism, Richard spent 15 years working with Fortune 500 and tech companies, including at Citibank where he co-founded the first bank-centric payment system.

But how did it all begin?

PS:

Want to learn about new guests & more fun and inspirational figures/initiatives happening around the world?

Then use the form below to sign up for STIMY’s weekly newsletter!

You don’t want to miss out!!

Who is Richard Lui?

Richard Lui is the son of undocumented migrants and his “real” family name is Wong! He shares how this name switch happened and why he ended up working at Mrs Fields Cookies instead of going to college.

- 3:12: Why Richard’s real last name is “Wong”, not “Lui”

- 6:05: Learning to be selfless

- 11:10: Learning kungfu from a Shaolin temple master

- 12:23: Working at Mrs Fields Cookies

- 15:41: Being exposed to politics

- 20:25: Going back to college

- 21:32: Working at KALX radio station, reporting on Senor Dianne Feinstein, Magic Johnson and Rodney King

From Entrepreneurshipto Journalism

After graduating from Berkeley, Richard started a 15 year career working with Fortune 500 and tech companies, which eventually brought him to Asia.

While in Singapore, he decided to pivot into journalism by working at Channelnews Asia at a time where Southeast Asia was going through a major political upheaval, which included the resignation of Mahathir in Malaysia!

- 24:04: How Mike Breslin influenced Richard at Clean Environment Equipment

- 16:18: Working at Citibank in Singapore

- 29:38: Working at Channelnews Asia

- 31:19: Working at CNN Worldwide

- 35:36: Winning the Peabody & Emmy awards

- 38:19: Reporting on humanitarian issues & offering a helping hand

- 40:00: Being a 7-year-old feminist

- 42:02: What feminism means to Richard

Caregiving

Richard is most known for his caregiving space. An area he is very passionate about after learning that his father had been diagnosed with Alzheimers and he would need to make sacrifices, including going part-time!

He also shares the inspiration & highlights of his latest book and feature documentary, Sky Blossom, and how it has impacted him.

- 43:36: Learning of his father’s Alzheimers

- 46:59: Traveling ⅕ million miles a year

- 47:48: Coming up with a family caregiving plan

- 48:36: Knowing when to let go & whether they are keeping their dad around for too long

- 52:59: Richard’s new book, Enough About Me: The Unexpected Power of Selflessness

- 54:49: Three lunches

- 56:26: Why Richard produced Sky Blossom

- 58:07: The meaning behind “Sky Blossom”

- 1:00:59: Why joy is featured so prominently in Sky Blossom

If you’re looking for more inspirational stories of people in the entrepreneurial space, check out:

- Ep 38: John Kim – Managing Partner & Co-Founder of Amasia (thesis-driven VC on climate change & sustainability), vlogger, musician & serial entrepreneur

- Ep 26: Cesar Kuriyama – Tech entrepreneur & Founder of 1 Second Everyday

- Ep 24: Malek Ali – Founder of BBM 89.9 (Malaysia’s premier business radio channel) & Fi Life

- Ep 8: Barbara Woolsey – Freelance Journalist with Reuters, Guardian & Telegraph

If you enjoyed this episode with Richard Lui, you can:

- Tag us at @RichardLui & @sothisismywhy

- Tweet your thoughts & takeaways from the episode to Ling Yah here!

Leave a Review

If you enjoy listening to the podcast, we’d love for you to leave a review on iTunes / Apple Podcasts. The link works even if you aren’t on an iPhone. 😉

Send an Audio Message

I’d love to include more listener comments & thoughts into future STIMY episodes! If you have any thoughts to share, a person you’d like me to invite, or a question you’d like answered, send an audio file / voice note to [email protected]

External Links

Some of the things we talked about in this STIMY Episode can be found below:

- Richard Lui: Website, YouTube, Twitter, Instagram

- Sky Blossom

- Subscribe to the STIMY Podcast for alerts on future episodes at Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Stitcher & RadioPublic

- Leave a review on what you thought of this episode HERE or the comment section of this post below

- Want to be a part of our exclusive private Facebook group & chat with our previous STIMY episode guests? CLICK HERE.

STIMY Ep 41: Richard Lui - MSNBC & NBC News TV News Anchor

Richard Lui: So I told my dad that I was getting bullied.

But he said, you know what, Richard, you can decide either fight or you can just keep on getting bullied. And so you decide.

So I thought about it and went back to him and said, okay. Yeah. So what are the ideas? Well I know of an actual Shaolin temple monk who just came to the U S.

Who was there for five years and trained there and he can teach you Kung Fu.

And I was thinking, okay, I'm an Asian kid being made fun of because I'm an Asian kid and you're going to teach me Kung Fu like I'm already the Kung Fu kid, and now you're going to teach me Kung Fu.

In the end. I mean, I laugh about that cause it's almost like insult to injury in a way, but it did help.

Because that was the time like Bruce Lee had just come out in the seventies. And it was lots of films, right in the eighties too. And so everybody was scared of Bruce Lee and here I was a little Asian kid who could do a couple of Kung Fu moves and you're like, Oh, stay away from him.

So it did, work in the end, but very funny what he thought the solution was.

Ling Yah: Hey everyone.

Welcome to episode 41 of the So This Is My Why podcast. I'm your host and producer, Ling Yah, and today's guest is Richard Lui. An American journalist and news anchor for MSNBC and NBC news. He was formerly at CNN worldwide, where he became the first Asian American male to anchor a daily national cable news show.

But how did he end up there?

Well, firstly, he didn't go straight to college. He didn't enjoy school and decided instead to work at Mrs. Fields Cookies. Eventually he did return to finish college and went to Berkeley. Before spending 15 years in business with Fortune 500 and tech companies.

While based in Asia, he decided to pivot into journalism. Starting with Channelnews Asia, before heading to CNN Worldwide and now MSNBC and NBC news. And in the process, received the Peabody and Emmy Award for his team reporting at CNN during Hurricane Katrina and the Gulf oil spill.

More recently, he's known for his work in the caregiving space. Caregiving being something very important to Richard after discovering that his father had Alzheimer's. And he would need to go part-time to provide proper care for his family.

He shares the sacrifices involved, including traveling over half a million miles a year between New York, where he worked, to San Francisco, where his family was every week.

And the book and feature documentary, Sky Blossom, that's coming out to showcase the amazing work that caregivers all over the country are doing.

Are you ready to hear Richard's inspiring story? Let's go.

So I thought I would start with a fun fact that I discovered about you, which is that you are known as Richard Lui but your last real name is Wong. So how did that name change come about?

Richard Lui: What happened was because of the immigration rules in the United States.

There was a law that was passed that did not allow those of Chinese descent, those from China to come to America. And it was the only law ever created. It was called the Chinese exclusion act. And so what happened was no more Chinese, unless you were wealthy or aristocratic came to the U S and that was in the 18 hundreds.

1882 was the year the law was passed.

So what happened in 1906 is this great earthquake in San Francisco. And it destroyed all of city hall and its records, everything burned down. So what the mayor said was okay. Everybody can come down to the new city hall and claim six to eight children.

I can't remember.

And so what all the Chinese folks did as well. They said, since we can't get more people here, we're going to go down and claim six to eight children. And even if we don't have any children, and so they claimed that, and then they sold those names in China and then people would come over to us using that name.

They buy it. And those became paper sons and paper daughters. Cause only on paper where they, the son or daughter of that, parent of that American. So that's my background. My grandparents bought the name Pang Liu and his real last name was Khan Wong. that's the other side. So his name's not pawn, but his last name was Wong, but he said he was a Liu Louie.

So that's why my real last name is Wong. And it's because of immigration and immigration laws that caused my grandparents to come to America illegally. And I always say I have the wrong name.

Ling Yah: And your father, as I understand it, was a pastor and also a social worker and your mom was a school teacher, but also a church choir girl.

So I imagined that you must have grown up in a very nurturing and faith driven environment.

Richard Lui: Yeah. My dad being a pastor. Yes. And he used to try to force us to go to church and do all these things. And the reputation of pastors' kids is widely known that we sometimes are not the best kids.

My mom was not that way. She said you go to church if you want, or you don't. I can't force you. Yeah, my mom was a choir girl. She grew up in Los Angeles. She was born in China, came to America when she was two. And she was able to come to the United States because her great, great grandfather was a US citizen.

it was different on her side. So she had a US passport because her father was a us citizen and he was a US citizen because his father was so that's how it worked for my mom. My mom used to sing every night, get on the piano and play church hymns and sing. And music has always been part of what she loved to do.

So not only singing, she learned different instruments, the jazz guitar, the guitar, the violin, the piano, as you just heard. So yeah, she's a very musical person

Ling Yah: Your parents must have really tried and inculcate the spirit of giving back to society and bringing you along to help out with the community.

What was that like? are there any stand out moments?

Richard Lui: The thing that stood out, I think Ling Yah, is that they picked professions that were, I thought very selfless like my mother being a school teacher, she decided very early when she had four children that she was gonna stay home and take care of us.

My father was a youth pastor and he couldn't make enough money. So he became a social worker. And when he became a social worker, that again is not a high paying job. So there we were, family of six, one salary. A social worker and we were so poor we needed food stamps and we got help with the welfare system.

but that didn't change them. They still wanted to do what they did. My dad still was a social worker. My mom was still a school teacher. They weren't going to change their careers.

They never, by the way, ever said, you gotta be this way. You gotta be, you know,, the only thing my dad did was said you have got to go to church.

That's the only thing he did, but they never said you had to live a certain way or be a certain way they would show it. I think it would just in their lives that my mother, when she went back to work When I was in middle school, she would get offers to become the vice principal or move to a better school and get better pay.

But she'd always say no. And she'd say no, because she would go, well, no, this school needs more help. I'm going to stay at this school. and as she got seniority, they even asked her and said, Hey, Mrs. Lewis, Hey, Rose, what school do you want to go to? So she picked the school with the lowest scores in the city, and that was the school she wanted to retire from.

So I think those decisions and the way they carry themselves to this day with the right kind of values, I'm absolutely committed To their kids to make sure that they would be good people, but not in a forceful way, not in a way that said, you gotta volunteer here and you gotta do it.

And they never said any of that. Never, never, never.

Ling Yah: The theme of selflessness is so present in your life. But I wonder back then when you were a child, was it something you understood?

Because I imagine that if I was living on food stamps, I would look at my parents and go, why are you not putting us first?

Why are you going to work to give other people food stamps but needing it yourself.

Richard Lui: Yes. No, you, you, you can read my mind Ling Yah. That's uh, what I thought later in life at the time, I didn't know. I was just figuring, well, this is what you can do. This is all they can do.

And then my mom not taking the promotions despite us needing the money. It just became more and more evident about her commitment and why she became a teacher. My mom would volunteer a lot and she still had a job and she would have to cook for the family and clean. And, , that's a whole thing that I didn't like I'd realized later.

Why does she do it? Why isn't my dad doing it at a certain point?

And my dad was just a little bit helpless cause he was the youngest son of 13 children. What that means is that, and there were four sons, nine daughters, and my dad was the little Prince. So when my mom married the little Prince, cause you know,, Asian families are like that, I'm sure she was just like, ah, gee whiz.

I've married into the exact same situation I grew up in because in her family, my mom was the youngest daughter. I was wondering why she was a night owl. Like she'd always be up late. She'd be doing all her stuff late. That's when she would get stuff done.

If you will. And it was because in college she would tell me the stories and I kind of put it together later in my years is that she would have to cook the meals, then go work at the family store, then go to class, then come back and cook dinner. Then clean up, then work at the family store, then close the family store.

Do the books. And then finally, what time does she have for herself to study? Late. 10, 11, 12, midnight, but she never complained. And so later on, I think maybe five years ago, I was like, mom, you were the youngest daughter. And this is what I think is probably what happened. Is that what happened? Oh, I guess so.

I was like, oh, I guess so. So I think that she's very aware of it, but she made the best of it and she was the smartest person in her family. But she decided to become a school teacher. She's an amazing artist. She's a sculptor.

I mean, I've seen some of the artwork that she did when in high school and Ling Yah, I gotta tell ya, I wish I got a little bit of artistic capability because the sculptures that she did were just like, wow, she was in high school. And you could sell this professionally. So she's one of those left brain, right brain people. But I think both sides came together along with a good heart.

And so it wasn't about maximizing those things that we often associate which is quite prevalent as, you know, success, career, money, the blah. She moved past that.

That was not her goal. And she will tell you, I want to say, like, why would you do that mom?

Well, she would say it's because of her faith and her religion. That would be her answer.

But yeah, they were kind of that way, as long as I can remember. Well, the one thing that they did do is they took me down to the YMCAs to volunteer. I didn't have to do it more than maybe a weekend, but I kept on doing it for years and years and years and years and years and joined a service club and then we'd started helping other folks.

And then it just kind of um, was all in the family, I guess.

Ling Yah: I understand that you were bullied in school, and that led you to learning from a Shaolin temple master. How did that happen?

Richard Lui: Well, yeah, I didn't like school, but I was bullied at school as a little kid cause I was a small little Asian kid so I told my dad that I was getting bullied.

I didn't use that word. I didn't know what it was, but he said, you know what, Richard, you can decide either fight or you can just keep on getting bullied. And so you decide.

So I thought about it and went back to him and said, okay. Yeah. So what are the ideas? Well I know of an actual Shaolin temple monk who just came to the U S.

Who was there for five years and trained there and he can teach you Kung Fu. And I was thinking, okay, I'm an Asian kid being made fun of because I'm an Asian kid and you're going to teach me Kung Fu like I'm already the Kung Fu kid, and now you're going to teach me Kung Fu in the end. I mean, I laugh about that cause it's almost like insult to injury in a way, but it did help.

Because that was the time like Bruce Lee had just come out in the seventies. And it was lots of films, right in the eighties too. And so everybody was scared of Bruce Lee and here I was a little Asian kid who could do a couple of Kung Fu moves and you're like, Oh, stay away from him.

So it did, work in the end, but very funny what he thought the solution was.

Ling Yah: And after your high school, you didn't go to college, but you started working at Mrs. Fields Cookies, which is an unusual decision to make

Richard Lui: you're being kind. You're being very kind, unusual as an understatement, I think in a way.

I hated school.

I almost flunked out of high school, flunked a grade. I got kicked out of one high school, then went to another high school cause I missed like a hundred days of class. So the second high school is when you had to have 200 units to graduate and no matter how many extra classes I took, or no matter how much summer school I would do, I would still come up 2.5 units short.

And so I was going to flunk basically.

But the principal was very kind and selfless cause my mom came down to meet with him and she didn't tell me. But she met with the principal and then the principal found me after my parents left the parent meeting, and he says, Richard, I just talked to your mom about half an hour ago, or this morning, whatever it was, your dad was there too.

, your mom was crying. And then I was like, Oh, okay, that's the signal. You better get it right now, Richard, mom's crying. And , what he said is, , your mom's a teacher, I'm a teacher and we help each other. And so Richard, I'm going to think about how to get you to graduate and I'll come back to you.

So he comes back to me a week later and says, Richard, I'm going to do something that a principal can do. I'm going to assign a special dispensation. So you can graduate with two and a half units short. But you have to take all of these extra classes. You have to take all the summer classes, even after you graduate to do this.

And I did it cause there's no way. I mean, once, once my mom came down, my dad and my mom was crying. I was like, Oh, you better shape up. Do it for her. Right. Do it for her.

But then I didn't go to college cause I didn't enjoy school at the time. And then that's when I worked at Mrs. Fields cookies for four and a half years.

And I got fired in the fourth year because I got bored. But before that There were 500 stores in the United States and of those four or 500 stores. I had number 10 in sales. in the time I had it, I got it to number one.

Ling Yah: Your time at Mrs. Hill's, you have described it as one of your galvanizing epiphanies. Why was that?

Richard Lui: It was really sort of weird, like who. Doesn't go to college and who works at Mrs. Fields cookies and thinks that it's what they absolutely wanted to do. That's the stereotype, right? That's the running hypothesis.

For me, it was exactly what I wanted to do. It was where I learned amazing things about management, because I had three stores and I had 35 employees. I had to manage, I had to teach new store managers and I was 18 turning 19. And I really enjoyed it. I loved the cookies too.

We were bakers in my family. We all love to bake, so it was everything I could imagine. And the lessons of management really stuck in me from that.

And it's interesting. We had something that Mrs. Fields cookies called cookie college, and you would fly out to Utah and in a state of Utah, you would have a bunch of managers getting trained.

And so. All of that was super helpful for my understanding later on in life about managing people and dividing and conquering, right, as a team,

And wasn't this around

Ling Yah: the time that you were also quite active politically, and you were campaign manager for Alan wrong. So what spurred you to do that? Cause then you decided to go back to college.

Richard Lui: Yes, that's absolutely right. So my uncle family friend, you know, how in Malaysia and in Asia people are your uncles. But he was a close friend of my parents. But also a politician.

And so he invited me to come on as a campaign manager and here I am I don't know, 1920, 21, whatever it was.

I write it in the book. cause I wrote everything down cause he had to go back and actually put down the dates, but I had never done anything like that. I really enjoyed the political process and I had no idea what I was doing. This is his third election and he loses and I'm his campaign manager.

But that lesson. Was super strong. I consider uncle Alan Wong, he opened my brain up to politics and how you need to lean in that politics is by its design hopefully to be selfless because we're contributing to our society, right? We're giving to create better systems of distribution, of scarce resources and equity.

Fast forward 30 years.

And he is now stuck in a wheelchair because he was paralyzed from the neck down. Cause he have an accident that he fell and I'm getting an award from an organization. He used to lead in San Francisco and he goes through the effort of getting into a van and coming to present the award to me. And I was just like, oh gee whiz, this guy's amazing.

He's been living in a wheelchair for 10 years. I still talk to him. When I see him. I say, uncle Alan, , the reason why I report on politics is because of you. We would laugh and blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. But when he was up there on the stage and he read the speech and he's in a wheelchair and he can't move his head and he gave the speech.

You can just imagine Ling Yah. Woo. Man. It was hard to keep the tears away. Not that you want to or need to, but it was just like, wow. He passed away when I was writing the book. And so in the chapter about career payoff and mentorship, I talk about him. And the reason being is it was really special because that same organization that he led for so many years then wanted to give him.

A lifetime achievement award posthumously, and asked me to be part of it, to give it to him, to give it to his son, actually. His son and myself were very close friends. It's just very special that that relationship from way back when right. In city college. When I went back to community college and him showing me what giving of yourself might be had given back to me so many ways.

And so many times along my journey so far.

The college part was I realized I could not be a cookie maker for the rest of my life. interests change and we re identify what we are and who we are many times in our life.

And the question is, do we act on it? And do we put a plan together to realize that potential satisfaction. And that was the point where I was like, I can't do cookies anymore. I've loved it for the last four years, three years, maybe, but now it's time to move on. And then I applied to city college of San Francisco and it's a community college go Rams.

And that did lead into me volunteering for my uncle, because he was also on the board. That's what he was wanting for the college board. And I said, Oh yeah, community college is important. It is great. Cause you know, I'm benefiting from it. It's affordable. It's only like, I think it was paying $200 per semester or something.

I can't remember what I was paying. Almost nothing. And so community colleges accessible education is so important and had there been a community college in Chinatown. When my aunties grew up on my dad's side, it would have been a wholly different life for them. None of the nine I was talking about the nine daughters, and four sons that my dad comes from.

None of the daughters got any. College education zero, but they just opened a community college location in Chinatown. cause I was touring it because I think I had just done the commencement speech for city college and I had to God tell Ling Yah, when I went back many years later to give the commencement speech.

That was really, really special for me. I know the importance of these two year institutions are so important to the education of most Americans and most individuals globally, I'd say the four year institutions and the equivalent around the world are very important, but it's also the junior colleges as they call.

Sometimes they're super important for that group that is trying to get back into education. Like myself, but yeah, I was wondering what had been like, if my aunties my dad's sisters, if they could get that education, they never got it.

Ling Yah: But you got an education at a community college, and then you decided to go to Berkeley, but I don't think it was a smooth process.

Was it?

Richard Lui: No, ma'am I applied to two schools. Berkeley was one of them. They rejected me. I got the little skinny letter. And I was upset because I said the master plan of education in California, basically the government, they lay out a plan about how they're going to educate their residents was created for people like me, older, working out of high school, poor and went to community college.

So I wrote them another letter because my essays for the application were horrible. When I read them later, my essays were horrible for the original application, but the letter was spot on and I got the fat envelope about a week later. And that's when I went to Berkeley and Berkeley was also another one of those situations where I was like, wow, what a great educational experience that would change my view on the world and what I could do.

City college was great. Berkeley was great. And then later I went to Michigan for an MBA. Michigan was great. So go Rams, go bears, go blue.

Ling Yah: And you said it changed your view, was it because one of the big things was you reporting for KALX and you were quite active, right?

Richard Lui: I was, yeah, I mean, it was a KLX Cadillacs was the radio station.

It was a news, and music. I applied and I got the job and getting the job there was volunteer. And that was probably at the time I thought it was my first news or journalism job, but I don't believe it was, I'll tell you why after But I was reporting on Senator Dianne Feinstein now. Who was the first woman to represent the state of California in the us Senate that was covering her election.

And also covered magic Johnson, getting AIDS. And that was a big deal, right? HIV. It was a big, big issue back then does the early nineties. And I also covered the beating of a black man by police caught on tape, Rodney King and little did I know that all of those would follow me throughout my life.

Now that I'm a journalist today and reporting on similar storylines like Rodney King. It's hard to believe the time's gone by, but nothing's changed or very little has changed when it comes to race in America on that point. But yeah, KLAX was fantastic. Really enjoy it.

I was trying to get the tapes of. The reporting from way back then there are none. There are none. Yeah.

Ling Yah: Were those very transformative experiences that convince you that I want to be a journalist because these are not easy topics to cover,

Richard Lui: Ling Yah, the answer is no. Because after that when I graduated, I worked in marketing and advertising and it worked in tech.

So, I guess if it was inspirational, it's not something that I immediately moved into. Now that I've been a journalist for 15 years professionally and getting paid for it I do think back to that time of KLAX. What it put in my brain?

But the first time I think. I was doing something journalistic was actually in high school when me and a buddy put together a newsletter at a church camp and he, and I would write it every night overnight, and then slip it underneath everybody's door.

And it was the daily bugle was the name of this newsletter, this newspaper that we would put out for every day. So it's interesting because journalism was kind of like a skipping rock. Boom. Right. And then finally it landed 15 years ago when I left a startup in Singapore and said, I've always wanted to try to be a journalist.

Let's go. And so I tried it and 15 years later here I am

Ling Yah: Before being a journalist, you joined clean environment equipment, and I believe you did that because you met this guy called Mike Breslin.

Richard Lui: Yeah. So when I was at Berkeley, I was looking for a job and I went to the job board and I saw, Hey, there's a job from a place called clean environment engineers.

And they're looking for a marketing assistant. So I applied, it's a small technology company that cleans up underground, fuel spills. So, , you've seen the oil tankers. , in Southeast Asia and , they'll come in and then they'll well in the U S a lot of those tanks are very far inland and they will well everywhere in the world, they are, and they'll leak into the ground.

So he had technology to clean up those spills. I would leak into the ground water that you would drink. Yeah, he was great. I worked with him for five years. In the book, I talk about him a lot because I think it was a great mentor of good values.

Ling Yah: You said his servant leadership inspired you, especially.

I mean, he really led during the recession as well, which was a very difficult time.

Richard Lui: Yes. During the recession, he paid himself $0, so that all of us could keep a job. He reduced our pay by. I forget 20 or 30%. I can't remember what it was 20%. But he reduces it by a hundred percent, but he didn't tell us.

What he did after that Ling Yah, is he created a retirement system for us and for a small company that grew from 10 people to 50. When I left. You don't create retirement systems for it's very expensive to create a retirement system, but he did it. he was great. He was really great in that he would say, Richard, what are you talking about?

Nothing big. And I was like, no, this is, you don't understand this. This is good way to do business is the right way to do business, treat your people like people. And That inspired me later on during this latest recession that we've all lived through and I think are making it through the other side.

When I had an employee whose job also got canceled because of the recession.

I said, I'll pay him then. And so he became an employee of the group that is building the movie and helped to build the book. And I think back because of Mike Breslin, when he did the same for us, he didn't think twice, he just did it.

Ling Yah: And so after that you were at various positions that Lazarus, and also at Mercer, before you eventually moved to Singapore for Citibank, what was behind that move? I mean, it must have been huge shift to go from the States to Asia.

Richard Lui: Hm, it was truly enjoyable. I mean, I enjoyed Asia. This is in 2001, it was a big shift, but man, did we love it.

We were creating a FinTech business model related to payments. And we were working with Citibank, Maybank and ABB and AMRO. And it was the first of its kind. It was a bank centric payment system. We had it patented. Everybody thought, ooh, this new tech thing, right.

It was the middle of the tech boom. And then the bust of Oh one. we learned a lot, put it that way, but it's great to be an Asia and , that we're working with some great banks, some great institutions that we're really being innovative about how to reduce costs in payments.

Again, a really important experience for me because laying out that if I didn't do that, I don't think I'd be a news anchor.

Ling Yah: Why'd you say that?

Richard Lui: I was originally going to business school when I went to Michigan and then I went to Singapore to do the startup, to move away from small companies instead work for big companies because I was working for technology startups, and I wanted to move into fortune 500. So I went to MBA and I wanted to work in strategy consulting at Mercer and Mercer was very kind to me now.

Oliver Wyman. I just gone down that route of strategy consulting. I would have been in New York or San Francisco and just going to do my projects. There was no business to develop. There was no business to be sold. There was no business development. There was no pitching to investors.

There was no making new relationships internationally, right? Not to that degree, right where we were the principals, we were the four founders of the business. It was up to us to push and make it happen with Citibank, ABN, AMRO, and Maybank. so when we sold it to Singapore technologies then we stayed on a year.

That was sort of the crux of, okay, we finished this through. Now what?

Now, if you don't have, now what's in your life, those great intersections. Sometimes you're just running on the treadmill, ? You don't, I'm talking about running, running, running as a lawyer you're running and running, running transaction after transaction client after client, right, case after case project after project. Got to become a junior partner, got to become a partner, got to become a managing partner, whatever it is, right.

Same with consulting.

So, because I had reached a natural end to that startup, we sold it. We done our one year helping them. Take it in, into their system. We finished doing that and we're like, okay, well, do we go back to consulting? Do I go back to my job? Which Mercer at the time was very kind and they still held it for me.

And the other founders, they went back to their jobs. One went back to McKinsey, one, went back to Proctor and gamble. many of us did. And I didn't. I decided I would give it a go. Cause when you reach those intersections, everything is open and new again in one of those open and new things for me was to consider journalism and my partners, my fellow founders, I asked them, should I do it?

Should I not do consulting and instead become a news anchor. They said, don't do the news anchor thing, go back. Cause my first job as a news anchor was at channel news, Asia and Singapore, and they were kind enough to take me in and I was there for a year and a half, two years. And then I moved to the U S to work for CNN worldwide.

Ling Yah: when you were at Channel News Asia, that was a pretty interesting time. Because the Sukarno family was defeated. Our Mahathir just stepped down. Huge point in time.

Richard Lui: It is, I mean, huge from Malaysia. Absolutely. Change of an era, right. In Malaysia, specifically as a change in Taiwan. I mean, it w it's Indonesia.

I mean, we were just seeing great. Eras and politics change and getting to cover. All of that was was an honor to, I was learning a lot, right. And Asia is moving so quickly since then, is it feels like a hundred years ago. Right. But yeah, it was an exciting time politically.

Ling Yah: Did anything stand out for you during that period of covering what was for us, very huge moment, politically?

Richard Lui: I think what stood out for me was, the big sort of what is next, are we going to see the next generation of what politics might mean in Southeast Asia or when you see more of the same or something in between, we saw something in between but the opportunity for the next generation to get in there and be part of the system, because many of these were younger era's right. They hadn't been around for hundreds of years.

Instead, you had an era that was very special to Malaysia, Indonesia, and Taiwan, but would they now, you remember in the new millennium, people were wondering, well, in the new millennium, are things going to be radically different?

Cause we just passed 2000, right. Everyone thought, oh, everything's going to be brand new. Now we have new leadership in Malaysia, new leadership in Taiwan, new leadership in Indonesia, who would be those new leaders that would rule and help lead their countries into the new millennium. I think that's what the thematic I took away from it.

Ling Yah: And was it an easy transition to go from channel news Asia to CNN?

Richard Lui: Channel news Asia and living in Asia for the amount of time that I did. And then living in, Spain when I was in college. It didn't make me an expert of international policy or politics, but it did prepare me for understanding the differences of countries that they're there and that you need to be respectful of them.

And that just because I come from the U S and my view is one it's only one. And it's just my view. So transitioning to CNN worldwide I was well-prepared because of what they trained me at channel news Asia, cause they had me produced, they had me report, they had me anchor. And that was all very helpful.

You got all of those exposures edit, tracking, using our voices like we're doing right now with podcasts. All of those were lessons I got from channel news Asia. So they prepared me very, very well for what I was about to get into.

Ling Yah: Did you ever have any doubts that you would not survive this totally new view?

Richard Lui: Yes. From the beginning, I thought you got to go for it and if you don't get it done, you can do something else.

I was lucky enough to go to good schools that gave me good skills. And I felt if I didn't make it to any of the networks that I would just go back to business consulting because I also loved it.

I love problems and solving them and like creating new, value new models that will solve problems and responsible ways. But yeah, I was like, I don't know, I have no idea, but you gotta go for it. So the interesting thing is that I owed Mercer a lot of money because they paid for half, my education.

And so when I got my first job at a channel news Asia it wasn't a lot of money compared to what I was going to get paid as a business consultant. And so I actually made negative money my first year. Cause I had to write a check for 70,000. USD back to payback, Mercer, cause they were so kind enough to pay for my education.

But the deal was, if you don't go back to work for them, you got to pay back the, gift. So I didn't go back. I had to write the check at two installments. I had to write two checks and it was the biggest numbers I've ever seen. And I made negative money. So Asian parents were not happy about that.

All over the world.

Ling Yah: But your dad wasn't that against it?

Richard Lui: No, he wasn't. No. That's why I said Asian parents all over the world were upset with me instead. My dad, when I called him I said, Hey, you know what? I'm gonna. Well, I talked to my mom first and she said, okay. And you talked about and tell him what he thinks, tell him what you're gonna do.

And I call and I tell them so I'm not going to take the job and I have to write this check and I'm going to become a news anchor or attempt to be. And he laughed.

He laughed. He said, Richard, I always knew you were a different kid. That's great. Go do it. But he laughed.

He wasn't laughing at me. He was laughing with me, right. Just the really you're going to do that said yeah, I'm going to do that. Okay. All right.

Ling Yah: I imagine it wouldn't have been easy to make it in that field. So I mean, like you have said often that it's like a 25 hour per day, eight day a week job.

So what were you doing to make a name for yourself?

Richard Lui: Yeah. It's not an easy job. You just work hard and hopefully over time it'll come through. it's just been a lot of work and I've enjoyed it all. I mean, for my first started at 30 rock in New York. I worked 30 days straight. I've worked 45 hours straight. If you're in the business, everybody does it.

I'm not unique that way, but it is a big requirement.

Ling Yah: What separates a good from a great journalist, the fact that you were the first Asian American male to anchor national cable news show. And that was significant.

Richard Lui: Yeah, that was really surprising because I don't know if that's true, but there aren't a lot of Asian American males that are anchoring.

It's just not common.

The issue is we need more folks that want to do it, and we also need more folks to understand that it's important to have that representation. And when my colleague, she turned over to me when it happened and she was like, Richard, this is important. So I said, really?

So yeah, this is, what's just happened. I said, wow. And she was really kind of hurt actually, first of all, know, and do the research. Right. But she was my co-anchor and so it was very, very nice of her, but yeah, that's where representation does count.

It does count.

Ling Yah: I wanted to pick one thing that you did there before we move on to MSNBC, which is you got the Peabody and Emmy awards or the team reporting on hurricane Katrina and the Gulf oil spill.

So what was that like, just working with that team to cover something so significant.

Richard Lui: At CNN, it was just like, wow. It's really impressive to be able to work for an organization that is all over the world. And that has so much reach and I was honored to be part of the team and our team was huge. Like it was just all over the world. We're spread out to cover all of these different issues, whether it was hurricane Katrina or any other story.

CNN's ability to get to the location, anywhere in the world immediately was something I always was impressed by and honored to be a part of.

Ling Yah: Can you share a bit about how that happens when Hurricane Katrina happened? How did the whole team assemble and get onto the ground? Well, is it like?

Richard Lui: So we have what I'll call a strike team.

We have all of these containers ready for such incidents. Now, hurricane Katrina was by the largest in the United States history at that point for deploying international correspondents, war correspondents into a us city.

And that within itself was I think, questioning of where the country was and where it was going, because we had a lot of Issues of the questions of different groups of residents based on race, based on class, whether they were getting equal services, that was a big part of it.

Most importantly, that was to get people saved. And when when you saw so many people that were dead floating Americans in new Orleans, that was shocking. I think to many people that were used to seeing such horror and destruction in war or in other countries. And so the, deploying of all the resources that we had was aimed at not only to tell a story, but also to help the people.

That's when the business became more than just what it was doing as, a news organization, it also became a corporate citizen and was trying to think, how can we help the area on top of that?

So that was impressive in that every network was trying to do that for CNN, since I was with them at the time, that's what we did.

And I was humbled by that work and that group.

Ling Yah: So you were doing a lot more than just going there and reporting you actually on the ground and being a part of that kind of helping people

Richard Lui: Yeah. And when I was on the ground, helping people was really underlined and me helping people with maybe an overstatement was during the oil spill.

It had gone all across the area. And we were traveling just from East to West, every town that was by the water. And I don't know if we were helping people directly, but I know by telling their stories, that is part of helping people.

Ling Yah: Did you ever feel that there was a conflict between you telling the stories and people were just needing someone to maybe hand out food?

For instance, was that this feeling of conflict of, oh, I'm just this party. Where I could actually be actively helping.

Richard Lui: When it comes to health and safety, that's when the journalist, which is supposed to be removed and observing when you turn off the lights, you put on your human hat and of course, yes, you help where you can.

Me reporting on human trafficking has always been a difficulty of understanding that line of, When do you, you take off the journalist hat and put on the human hat and then you help, right? That was always difficult for me. Because we get to fly away and they stay.

So those who are kept as slaves modern day slaves and enforced into having sex, you do want to help and yeah, you have to be a journalist. What brings you there is your journalistic nose, right? Is your job as a journalist.

So when do you take off the journalist to cat and when you put on the human hat. And so that is why I volunteered for so long and still do on issues of human trafficking and gender equity.

Cause if I'm in a story, when you take off the journalist hat, then do you go in there and you try to take them all out? Well, are you capable of doing that? And I'm not because if I remove them, guess who's still there. When I leave the pimps and they will harm them and they'll harm the family.

And so what do I do when I take off the journalist's hat and be the human hat is by volunteering. For those sorts of NGOs and CBOs, and that's the way that I was able to balance out what I was learning and then doing something about it.

I know that telling their story was to me just as important because it, got the word out about this was happening.

Ling Yah: And so some of the NGLC work that included plantains national USA. You say that you are a seven year old feminist. How did that come about?

Richard Lui: I'm a seven year old feminist. And the reason why I say seven years old, because when I started reporting on human trafficking I guess 12 or 13 years ago, I started to see the same thing in every country I would report on it. And I didn't understand why women and girls were always the victims and survivors of human trafficking more often than not. 80% of the time.

And it's because in I should say all countries that women and girls are often seen as not first class humans.

And what does that mean? Well, it is different to different degrees. I know it's a strong statement, like in the United States women make 80 cents on the dollar. They make 80% of what a man makes everything else being equal. Why is that?

So that's the sort of case similar in every country. my mother, for instance, her own family. Why is it that the brothers didn't have to do the books or the cleaning? Why does she have to only study from 1:00 AM to 3:00 AM in the morning? How come her brothers didn't pick up and so that she could do that.

So she could study during normal hours. So that is what opened my eyes seven years ago. And the reason why I say I'm a seven year old feminist is because. I got a lot to learn. Right. The thing is just cause you're a guy and all of a sudden you say, yeah gender equity is important.

And that I will stand up for it. And I'm a feminist because of that. And it's a strong word and I know it can be polarizing. I say it in a way that hopefully is not polarizing. I don't want it to be polarizing only to say that I have a lot to learn. Because for you, Ling Yah, you have many more years of experience of what that means to be a woman in the world compared to me.

And so I don't want to ever say to you for instance, or any other women that, because I'm a feminist, all of a sudden I'm in and I get it. No, I don't. It takes a long time to learn what that means. And you are far more steeped in experience and knowledge on it then. Yeah. Then I would ever be, but I'd still, it doesn't mean I can't be part of the solution.

Ling Yah: What do you understand feminism to mean and how can other people think about that?

Richard Lui: For me, it means that I have male privilege. Just by walking into a room. I've never thought of me being the only male in the room or that I'm a man, then walking into a meeting, but just about every woman has walked into a business meeting and thought to themselves, I'm a woman walking into a business meeting just about every woman has.

I've never thought if I'm a man walking into a business meeting. I don't have to think about those dynamics. It's an important thing to remember. And so feminism for me means remembering that all of us should have the opportunity for equity regardless of gender.

And I know it also means to me that I. Have an advantage that I need to understand is not right, and that I need to work as a volunteer and as a learner to get it so that it isn't that way. And it is an embracive and understanding conversation, not an aggressive separatists divisionist approach. So.

Feminism and being a feminist is not that to me.

There are subgroups. There are many segments of women who face differing degrees of inequality. It's not like All women minus 20%. No, there are some that are minus 50%. There are some that are minus 5% and we have to remember that.

it depends on where you're from, what class you are, what ethnicity you are, what country you're in, these all fit into that equation.

Ling Yah: And so while you were working, you were volunteering in 2012. That was when something really huge happened personally. Can you share how that, or the chance by it?

Richard Lui: Well, 2012, there's a lot of things that happened. So my father we went to a gathering that we normally have every year. It's a Christmas gathering So all those siblings I've been talking about, we gathered with all the children come, we eat, we celebrate.

My father's younger sister comes over to me and says, Richard, your dad's forgetting his siblings names. And , they grew up as 13. They grew up poor. They knew each other's names. Like they were their own best friends. Right. You know what that's like? Because we see the stories, see the stories of, those families that, yeah.

They may grow up without a lot, but they have each other and it's really strong. Right. So when he was forgetting their names we said, we need to get a test. He said, well, really? I dunno and said, no, get it. And Oh, okay. My dad was a kind of guy that would, go to doctors. He was not afraid of them.

But this one he didn't, cause it's such a big idea.

This is a big idea that your brain was losing its power. And he went in and they said, yeah, it looks like you have early indications of dementia and then began that sort of long track of it being Alzheimer's. And today, so he's now seven or eight years, eight years in of living with Alzheimer's and it is the typical I've been told.

A lifespan after diagnosis of Alzheimer's is seven years typically. And then they pass. So he's done really well. I mean, he's eight years in and he can't eat. He only has a stomach tube for food, and I order the food for him that arrives every month.

He can't walk and he stopped talking about a year and a half ago.

But he's still there at least last time I saw him because of COVID I've not seen him in person physically in a year

Ling Yah: From that Christmas dinner and your Aunt Fanny came and told you, this is something that's the big deal. Was it something that was hard for you to grasp?

Because your father was the hero he was teaching you to shave and just teaching you all these things. And that's the possibility that You could be losing him in front of your eyes.

Richard Lui: Yeah. You know, certainly it was not easy, but I was more fighting to make it the best. It could be along the way.

So yeah there have been days of crying. There's been days of laughing, like I've never laughed before. And he has done and said things over the last eight years that were really, really helpful for me and my siblings and my mother too. And so, yeah, it's been tough for all of us and it's, made us age faster, but it's okay.

For instance, I would not have started speaking on caregiving in the United States. There's over 53 million family caregivers, no pay, no training. We're only 300. And what, 35 million people. That's a lot of family taking care of family, but we don't talk about it.

And so if it weren't for him sharing his journey, I want to try to work part-time because what happened therefore, as I went into my boss's office and I said, my dad has Alzheimer's and I may have to leave my job and she was amazing. She said, wait, hang on a second. I also take care of my mom in Florida.

We're in New York and she helped to find a place so I could work part-time. We talked about it earlier, right? It's an eight day a week job, 25 hours a day. And she in her selfless way helped me to find a solution . So I've been doing that now for six or seven years.

Ling Yah: You were traveling half a million miles a year, which is an insane amount.

Richard Lui: It's insane. When I hit half 1,000,001 year, I was just like, okay. that's just crazy. it was tiring and Ling Yah, it's interesting because the first four years I think it was okay. Then he started tripping and falling and he started getting lost and he, couldn't eat, he couldn't swallow, so he would choke a lot.

I'd be standing on the subway platforms and getting a 3:00 AM. Cause I, take the early flight out. Monday morning I finished work at 11, get up, get on the subway about three or four o'clock in the morning. And wait for the train to come and sometimes you'd stand there and just go, Oh man, this is tiring because you have to take two trains then you get there.

It's 10 hours door to door and you do that two or three times a month. It's a lot of travel.

Ling Yah: And how was it like coming up with the family caregiving plan? Because you have three other siblings as well.

Richard Lui: Yeah, well, I was working on it just now, in fact, before you and I talked because my mother just fell and she's now at home and she's doing well, but we're also now figuring out caregiving schedules for my mother.

And that's what we did before we had a shared. Spreadsheet that we'd lay. And I felt comfortable doing that. Cause remember back Mrs. Fields days, I had 35 people. And so the, part-time caregivers and then the family caregivers, , we just scheduled it out and it was not difficult for me.

It was difficult for the family because you have to find the people that can help because you can't do it alone. It reached the point where he had to get more help. And so we moved into a care community. My father left home and that was always a tough decision.

Ling Yah: I think that there's some of the difficult topics that have to come up would be, you know,, how long do you keep like your father around?

Because he's clearly going through a lot. how do you consider and deal with that kind of question?

Richard Lui: Yeah. The question I ask is, are we keeping him too long? Are we keeping him too long? And when I saw him a year ago, my sense was no. And the reason being as I would put on headphones, and then I had an amplifier cause he's hard of hearing.

And even though he can't talk. You know, he still looks with his eyes and he still can move his arms. And so I said, if you can hear me blink once, and then he blinked once I was like, Whoa, hang on a second. So I said, this is Richard. If you remember who I am blink once he blinks again. So he was still in there.

Now, the question is a year later, I don't know the answer. I've seen pictures of him. He seems like he's still the same. But yeah, it's a tough question. And I know it's going to be tough when we have to make that decision.

Ling Yah: And how has faith come into play throughout this entire period?

Because you have also described him as being watching him dying in front of me to being reborn, which is. Very faith like. So how has it carry you through this period?

Richard Lui: I'd mentioned earlier that it's like watching him die in front of me, but in the end, what the disease did do for him was to be reborn from the perspective of, he was a very happy person when the disease started to strip away some of his concerns.

Like, for instance, when he'd meet people and he would forget their names, he would say, I'm sorry, I have Alzheimer's now in the Alzheimer's community, that's not common. People don't often self declare. I have Alzheimer's when they forget something or remember that's why they forgot something. So he was funny that way. And. He began to hug people like for me and all the family, he would not that he was not that way before, but he would hug us, kiss us on the cheek and say, I love you.

You're so wonderful. You're so good. And then 30 minutes later, he would hug you and kiss you on the cheek and say, I love you. You're so good. You're wonderful. And so it was funny because it would happen, you know, in a day's time, dozens of times. he would do it genuinely with a smile all the time.

So yeah, he was a different person. He was in a way as he has been dying in front of us, as we all are in some way, he was also reborn because of Alzheimer's into this amazing person.

Even my mother, I bet you was like, who is this guy? He's so amazing. He's so nice. He's so loving.

Not that he wasn't before where he was, but it's just a different expression of it. Right. so yeah, I think there's a lot of religious and faithful themes. That have run through the experience for us because my dad's a pastor and it's just, the way that we are as a family, ?

And it has certainly been supportive for all of us, all of the children and my mother along the way in ways that I don't think we would have known otherwise. And so it's the mysterious ways as people say of the way it works. And I think for my family, all of us, just let it go. Like in the book, I don't typically talk about faith and religion.

This is not what you can know me for 10 years. I won't talk about it. Cause it's your business. and I respect that. If you are, great. It's your journey. If you don't, it's still, it's your journey, right. And it'll work itself out. I do believe.

So in this book, because we were talking about my father and about selflessness, , I did discuss it for the first time and it is a little strange, especially as a journalist and also me being me.

I just don't talk about it.

But part of being selfless is to find out and try to figure out what are the right ways to be vulnerable. And I ain't no expert but in the book, because we're able to think about it. We tried to be as open and vulnerable as possible because it's productive and to do it in a productive way, I should say.

But yeah, although the book is. Enough about me, the unexpected power of selflessness. I am definitely a work in progress. It's more like as a reporter. What am I learning about it? Not as, Oh, I'm an expert on it because I'm not an expert on that. But what I am is hopefully a journalist that really dug into it, brought into researchers really looked at the graphics and the data to get it to you, right.

But not for a second did we want to say, Oh. We know it all because we don't.

Ling Yah: This book you talk about which is available on 23rd of March this year. I was really impressed with the fact that it wasn't just your story, but you really, as you said, you brought in so many people in like Peilin and so they really collaborated with research and scientific facts to back it up and practical tips on how to be selfless.

So what was the whole original idea behind writing this in such a way?

Richard Lui: It was because I love business books and business books have the sort of cadence of not only good stories, but also research that backs it up and then practical applications. I like self-help books too, but this is the anti self self-help book because the focus isn't on.

Ourselves, but it is about how to get better so we can be better at helping others. Right. That's the idea. And so you have the researcher , Peilin Kesebir, which you bring up, who is a partner in the book. And as well, Alex Lowe, who's an assistant researcher to her we actually did pull out some of it because we had so much.

if you have too much, it's, sometimes it is right. It'll slow you down. And. The reason why we did it that way is because as a journalist, I don't believe you can just say it. You have to show it. And so what we showed it was through the research and then we showed it was through the exercises.

there's a scoring system in the book. Then if you wanted to see how selfless you are, you can fill that out. There's also the problem of being too selfless. And so there's also a scoring system in there to figure out if you give too much. And then, there are exercises that you can do every day with people at work and at home.

And we talk about relationships and selflessness. so hopefully there is somewhere some way. That you can take something away from it because the idea is these selfless things don't need to be like, wow. , like big gargantuan things like ISA mother, Teresa and Desmond Tutu, it can actually be every day.

Ling Yah: I mean you always talk about how you need to build your muscle tone for being more selfless. One of the things that stood up for me was chapter 11 on the three lunches. could you share a bit about that? Because I thought that was really interesting.

Richard Lui: Yeah. There is a study out of Stanford that wanted to find out if the indicators of prejudice against somebody can go away.

Is there a way of fixing it?

And so what they did is they took a whole bunch of respondents for the survey and let's just say, you and I we have prejudice against each other. So I don't like beige. You don't like gray. All right. But what happened is the measurements of the prejudice that we had before we ever met, we're like up here.

High. Then they had us meet three times. Coffee lunch, going out, doing whatever that meeting three times. And those indicators of having prejudice against beige and gray for both of us went from high to low, to almost just over zero. And what that showed is if we take the time to look outside of ourselves and reach out.

And spend time with other folks that we can get rid of some of the misunderstandings, why we don't get along. Why we don't like other people. Most often we don't though. Right? We stay in our comfort zones.

And so three launches is a very simple way of saying I'm going to try something. So tomorrow when I go have lunch or I am going to eat lunch or breakfast, how about I set up a time to meet with this person?

It could be over zoom. Like we are right now, or routines, whatever you use and over time. we'll get to a better place. So that's what three lunches is about.

Ling Yah: And so people can learn all these practical tips from your book but another final thingI wanted to talk about before we wrap up is Skyblossom. That was your directorial debut and has been named by Verizon as the top contender for 2021 awards season.

And I love that, you follow five students over three years and there were people of color from the military family and the youngest were 12 years old. They were caregivers at such a young age.

What was the impetus behind creating this feature documentary?

Richard Lui: Ling Yah, but I was talking about my dad and how all these things want to happen. When I started becoming a caregiving champion or caregiving ambassador, and I certainly would have done a movie. But the movie was inspired certainly by my own experience. And by talking to so many people. Around the world around the country about caregiving and that gap, like we just didn't understood stand that it's an important thing.

And it's really common, but not many people know about it. Even caregivers themselves don't even know that there's so many, they don't even call themselves caregivers. I want to do that. So it's a cultural problem.

And part of cultural solutions often do come from movies. Movies are a strong cultural underpinning or leg to the stool of the way we see things.

So then began that not for profit movie. That was called sky blossom, focusing on five student caregivers actually age 11 when I first started filming to 26. They're all doing really well. I just talked to three of them over the last two weeks and I'm talking to another couple next week.

The purpose is to show that family caregivers are of all ages. There's 5 million student caregivers like them, 5 million. And we just talked to five in that movie.

Ling Yah: Why was it code Skyblossom?

Richard Lui: Sky blossom is a, yeah, it's kind of a funny name, right? It's a hopeful name just by themselves.

We want to show that these are inspiring caregivers. These are inspiring students that you will cry watching the movie, but not because of sadness, but because of inspiration, it's an inspirational cry.

And sky blossom was chosen because during world war two, when parachute were used and planes were used in war, what would happen is if the troops rode behind the front line, they needed help.

The parachuters would come in on the planes, right? They and their parachutes open. And, but when the parachutes would open, they would look like blossoms opening. And so the troops on the ground would look up and say, Oh, here comes sky blossoms there in the sky. There's blossoms opening. All of the children that we chose for the movie are in military families.

And they are the same idea of help behind the lines. They're helping at home and they are like paratroopers parachuting in.

And second of all, they are blossoming. Because there are students growing up and they're blossoming to be amazing, amazing people. And that's why we call it sky blossom, diaries of the next greatest generation, because they are special folks.

They're learning how to care. When they become leaders and, contributors and collaborators in their communities all around the world, that's going to go with them, that understanding of caring for somebody else. And that is an important quality today that I think is missing in a lot of places.

Ling Yah: I think amazing people are not just those that you were filming, but the crew behind it as well. Cause you said you wanted to create one that they mostly inclusive crews. So you had a hundred percent female only people and like 1.5 million, pro bono in kind commitments over a four years.

How did you put that kind of a crew together?

Richard Lui: Yeah, we get lucky and the thing is we can be intentional and it can be done. I think there's a misunderstanding that it would mean. A compromise if you did something differently. And us having a 100% field crew was certainly different.

But we were better because they were all great professionals and it was not difficult justifying a hundred percent female crew. It was difficult to find good people, which they were. They're good at what they do. And 94% of all the money that we raised was spent on gender and ethnically diverse contractors, 94% of every dollar of all donations.

And like you said, a million and a half of what we raised Was pro bono work. People leaning in and saying, we're going to charge a 50%. We're going to give it to you for free. And I was just blown away by that. So I think that the takeaway from, that, the examples that you bring up is walking the talk and it can be done.

Ling Yah: I think 80% of them had caregiving experiences personally as well. So it was very, very personal to them.

One of the things I noticed in the film is that joy is such an important component of it. And you see these little things like laughters, or like the wife pinching her husband's butt, and I imagine that in the caregiving experience, joy is quite hard to find actually.

So was there a reason behind why you chose to feature it so prominently?

Richard Lui: Yes. Cause I found that my experience that there was a lot of difficulty but we always found a way to find new joy and new laughs.

And so I knew personally that there's a lot of tough stuff in there, but let's try to also create new opportunities of joy And that's what we were looking at for the movie and the the characters, the cast, if you will, because they did, Oh, like when we were filming. I saw like, oh, there they are.

They're laughing. And they're having a good time. We're not asking them to laugh. We're not asking Rasu to pinch Brian's, but we're not doing that. They're just doing it on their own. Right. And sometimes, we'll think of a topic like caregiving. Oh, that's gotta be a certain type or mood, right.

Instead, because we were all caregivers, men, 80% of us, as you noted were caregivers. We knew the complexity. We knew that there were a lot of layers to it. I know in the edit room, I was like, put that back in there's a part in the movie where. Chaz and Darren are laughing with each other and there, cause she's helping him with his legs because both of his legs were amputated and she's helping him put on the legs.

And it's very very intense, right? Cause this is not easy to, but then they're laughing at the end of it together. And I said, we gotta have that in there because they weren't laughing necessarily because they had done this for many, many years. They're laughing because they're a family and they can laugh.

We didn't want to overly stereotype that caregiving is negative, cause it can, there's a lot of really amazing things. All caregivers, I would say, or most caregivers will reflect on their caregiving time and say it was, yeah, it was really, really tough, but it was really, really great in many other ways, too.

And one of those pieces of brightness is the new laughs and the new joy.

Ling Yah: Do you feel that the filming of sky blossom changed you in some way?

Richard Lui: Oh yeah. Well, yeah. , I, I learned a lot. I was really blown away by these student caregivers and the depth at which they understood things, but we're often misrepresented .

You remember when you were a teenager? The older folks would go, oh, your generation is so selfish. All you do is this. I got that too.

And this is why when I was seeing them, I already had an inkling. I had an idea that they were not going to fit this stereotype.

I'm sure there are days where they're selfish.

There are days where they're teenagers. There are days they are students and we're human. We're allowed to be like that. But the majority of who they are was the opposite of that.

And so it changed me because it reaffirmed not only that I should try more often to think twice. Cause I try and I don't always do it before making any sort of assumption about somebody.

Cause if you look at all these five students, when you first meet them, you would not know what they have on the other side of the coin. Huge, huge, huge capabilities and understandings. Even one of the mothers said after watching the film, wow.

My kids really are special. I was like, yeah, they are. Yeah. But sometimes when you're in it, you don't see it.

Ling Yah: And then working with all these people and inspiring others as you are, I've noticed that you've said before you always work on three options at one time. So what are the three options that you're working on that?

Richard Lui: Well yeah, my thing is like every year on paper or on your shared document or on your, , whatever word doc option you use is to write down the three things. If you could do anything in the world, what would they be right now? Like they do any three things over the next two years. What would those be?

And right now, if it could be anything, it would be to stay a journalist and have the honor of working at 30 rock. It would be to do another book and do another movie because there's more things that need to be told. There's more opportunities to improve culture. There's more opportunities to improve learning.

Ling Yah: How can people listening to this, what's the best way for them to support you?

Richard Lui: if there is a story of somebody that you've seen that really inspires you because of the selfless things they do share.

Thank you, Richard, so much

Ling Yah: for your time.

I normally end all my interviews with these questions. So have you found your, why?

Richard Lui: I am rediscovering the why and the answer to it over and over again. And I'm looking forward to the next time I'm looking forward to this cycle as well, because the why is an important question and it changes and expect it to change.

And I do expect to change again.

Ling Yah: What kind of legacy would you like to leave behind?

Richard Lui: . That he didn't put too many people asleep

from watching movies and reading books.

Ling Yah: What do you think are the most important qualities of a successful person?

Richard Lui: Practicality.

Ling Yah: And where can people go to support you and follow what you're doing?

Richard Lui: skyblossom.com, if you want to learn more about the film and what we've been talking about, where it can be seen, it is going to be widely released on a major streaming platform and a major cable network or two in may, as well as in DVD.

And in theaters as well in may. And this is all a, not for profit effort. So I say all these things only it's not like we're socking away money in a bank, but it's all not for profit.

As I mentioned earlier, I've had 150 people involved in the movie and there've been a whole bunch of people that have been, , putting in their own time on the book.

For more information on that, it's Richardlui.com and that is also a not-for-profit effort. I'm donating all of the author proceeds to ARP Alzheimer's association and the Asian American journalists association.

So there's more information there and you can check that out or typically on social channels.

Ling Yah: And that was the end of episode 41.

The show notes and transcript can be found that. www.sothisismywhy.com/41

Alongside a link to subscribe to this podcast's weekly newsletter, featuring all kinds of inspiring things that I've found over the course of this week.

And stay tuned for next Sunday, because we will be meeting the country manager for StashAway, which is Malaysia's earliest and largest river advisory investment platform and cover how he went from being an associate in investments at Khazanah.

To his thoughts on ETFs, investments and the future of robo-advisory investment platforms.

Want to learn more?

See you next Sunday!