Powered by RedCircle

Listen at: Spotify | Apple Podcast | YouTube | Stitcher | RadioPublic

Welcome to Episode 85!

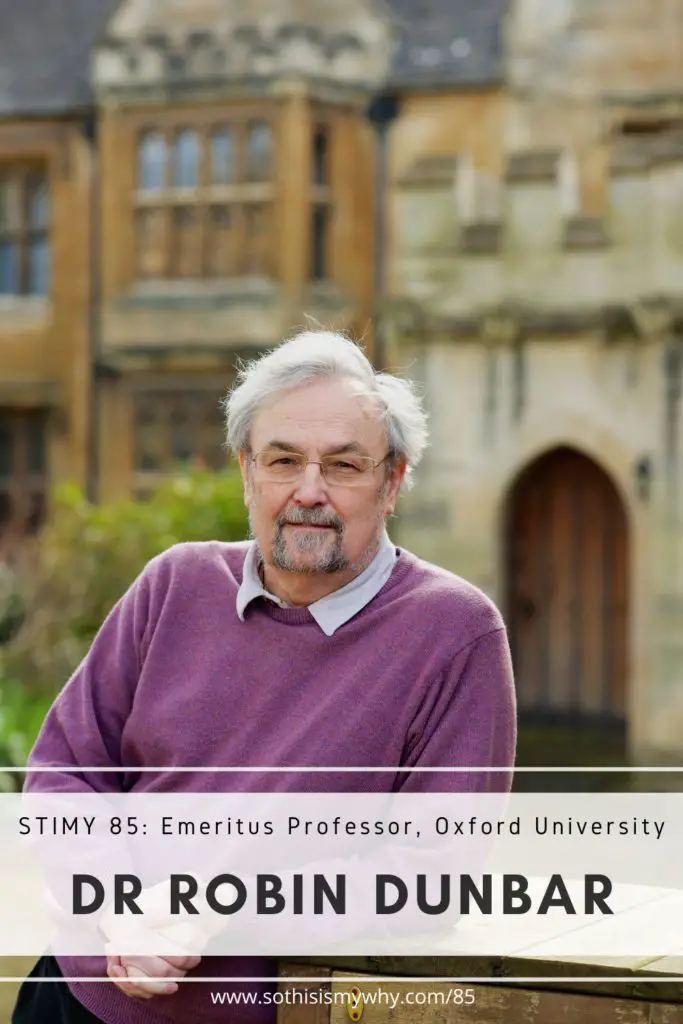

Our guest for STIMY Episode 85 is Professor Robin Dunbar.

Robin Dunbar MA PhD DSc(Hon) FRAI FBA is Professor of Evolutionary Psychology at the University of Oxford, an Emeritus Fellow of Magdalen College, and an elected Fellow of the British Academy and the Royal Anthropological Institute, and Foreign Member of the Finnish Academy of Science & Letters.

His principal research interests focus on the evolution of sociality (with particular reference to primates and humans). He is best known for the social brain hypothesis, the gossip theory of language evolution and Dunbar’s Number (the limit on the number of manageable relationships).

His publications include 15 academic books and 550 journal articles and book chapters. His popular science books include The Trouble With Science; Grooming, Gossip and the Evolution of Language; The Science of Love and Betrayal; Human Evolution; Evolution: What Everyone Needs To Know; Friends: Understanding the Power of Our Most Important Relationships; and How Religion Evolved.

PS:

Want to learn about more inspirational figures/initiatives & stay updated on latest blogs about Web3 law?

Don’t miss the next post by signing up for STIMY’s weekly newsletter below!

Who is Robin Dunbar?

Robin Dunbar is most known for formulating Dunbar’s Number (which ironically, was christened on Facebook, which sets the theoretical limit to the number of stable relationships a person can have at any one time.

But did you know that Robin grew up in Africa?

And he even wanted to be a philosopher!

- 2:56 How Robin got hooked onto human evolution

- 7:18 Why Robin wanted to do philosophy

- 8:50 Tracking monkeys & antelopes in Africa in the early 1970s

7 Pillars of Friendship

Given Robin’s expertise, we dive deep into all things relationships. Including what the 7 pillars of friendship are, and debunking common myths like, do opposites attract?

- 24:50 The 7 pillars of friendship

- 30:35 Do opposites attract?

Dunbar’s Number & Web 3.0

Robin shares all things relating to Dunbar’s Number and also, his thoughts on Web 3.0 and how to build a thriving virtual community.

- 35:47 Where Dunbar’s Number came from

- 40:11 Why 150?

- 45:06 Even dogs can be part of your 150

- 51:54 Can you guard yourself against romantic scammers?

- 55:05 The problem with Web 3.0

- 1:02:21 How do you build a strong virtual community?

- 1:10:58 Common misconception with Dunbar’s Number

- 1:13:18 Challenging 150

- 1:16:34 How listeners can help Robin

If you’re looking for more inspirational stories, check out:

- Nicole Quinn: General Partner at Lightspeed Venture Partners; investor and/or board member at Calm, Cameo, Lunchclub, Haus Laboratories (Lady Gaga), The Honest Company (Jessica Alba), Goop (Gwyneth Paltrow), Girlboss (Sophia Amoruso) etc.

- Richard Lui: MSNBC & NBC News news anchor; Peabody & Emmy award winner; top 100 in news buzz on its “Power Grid Influence Index of TV Anchors and Hosts” and one of “The 50 Sexiest in TV News”; author of “Enough About Me: The Unexpected Power of Selflessness”

- Debbie Soon: Co-Founder of HUG (Web3 accelerator, discovery platform & pre-mint fund), and former Chief of Staff at ONE Championship

- Guy Kawasaki: Chief Evangelist, Apple & Canva

If you enjoyed this episode with Robin Dunbar, you can:

Leave a Review

If you enjoy listening to the podcast, we’d love for you to leave a review on iTunes / Apple Podcasts. The link works even if you aren’t on an iPhone. 😉

Patreon

If you’d like to support STIMY as a patron, you can visit STIMY’s Patreon page here.

External Links

Some of the things we talked about in this STIMY Episode can be found below:

- Robin Dunbar: Website

- Subscribe to the STIMY Podcast for alerts on future episodes at Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Stitcher & RadioPublic

- Leave a review on what you thought of this episode HERE or the comment section of this post below

- Want to be a part of our exclusive private Facebook group & chat with our previous STIMY episode guests? CLICK HERE.

STIMY Ep 85: Dr Robin Dunbar (Emeritus Professor, Evolutionary Psychology at University of Oxford

===

Robin Dunbar: It turns out that even in romantic relationships the more similar you are, the longer the relationship.

The exception to that and possibly is the origin of this saying that that opposites attract is that it can work.

So what you're talking about with all these things, it doesn't matter whether it's a family relationship, whether it's how you get on with a member of your family whether it's a friendship and the usual sensitivity know whether it's a romantic relationship. The issue is simply how long is it gonna last, right.

And what are the forces that bring it together? And it turns out the seven pillars and the other kind of whole biological traits are very high predictive of how long a relationship, but how close the relationship will last. The more of the seven pillars, the more of these seven dimensions you can tick for somebody else the stronger that friendship will be. The more emotionally close to that friendship will be in the longer it will last.

What happens on Saturday night this is the example. The obvious example is you have an introvert and a negative. So, the extrovert wants to go out clubbing and dancing and partying, and the introvert goes, ah, can't we stay in and watch a film on the TV and have a takeout dinner. We'll send for a pizza or something and we'll stay in. And say, you have conflict already now, you know.

There's no compromise here. There's no middle road because you know, you either stay in or you go out. Whatever you do, somebody who's going to be unhappy. So it's how to minimize the amount of decisions which are complicated in that way.

Ling Yah: Hey everyone. Welcome to episode 85 of the So This Is My Why podcast. I'm your host and producer Ling Yah and today's guest is professor Robin Dunbar. Professor Dunbar is an emeritus professor of evolutionary psychology at the university of Oxford. And he's most well-known for formulating Dunbar's number.

Now what is Dunbar's number, you might ask?

Well, it's essentially the maximum number of relationships that one person can handle at any one point in time, which is 150.

You can imagine there are so many questions I had just around this. I went into this interview because I was curious about many things, for instance, who is Robin and what is his background?

How did he end up in the field of evolutionary psychology? Spoiler alert:; He actually grew up in South Africa.

His grandmother was a God-fearing Presbyterian Christian and a surgeon who spent her entire life in India.

Fun facts. Robin actually wanted to do philosophy until he realized that, well,

Robin Dunbar: philosophy is extremely hard. Only for people with very big brains. And I wasn't very good at it.

Ling Yah: We also talked about so many different things, including romantic scams and why they are actually pretty impossible to avoid, the science behind 150, what he thinks of Web 3.0, NFTs and the metaverse, and so much more.

So are you ready?

Let's go.

I was doing research and I realized that you became hooked onto human evolution because of your, and you described this in your book, " fiercely God-fearing presbyterian missionary surgeon grandmother". So how did she get you hooked onto human evolution?

Robin Dunbar: Oh, I think really by sending me a series of sticker books for essentially children which were very popular in the 1950s. So these are American produced booklets by the Audubon bond society, which is the kind of big wildlife, natural history society in America. It's very eminent and it's been around for a very long time.

And in the fifties they produce these interesting little booklets where you had to peel off stickers from central parts and stick them in the right places. They would illustrate different plants or different kinds of animals in different parts of the world.

All these kinds of things, different kinds of stones. They did them on all sorts of subjects related to natural history. And she sent me a box full of them actually. And one of them was on

I have to say with apologies to people who live in the Southwest of the USA, that the one that least appealed to me was the plants of the Southwest USA.

You know, I mean, this meant nothing to me. I was living in Africa. I'm not even sure I knew where the United States was, but the plants didn't interest me, but I was interested in the ones that were about animals.

And amongst these was one on human evolution. Now, you know, my grandmother was as you said a God-fearing Presbytarian Christian and very much not fundamentalist that would be too strong, a word, but she was fierce in her adherence to her religion.

But at the same time she was a surgeon. She was apparently a very good surgeon.

She had been a surgeon all her life in India, north India. And because of that scientific background that she had from her surgeon's training course she was always very interested in science and the science of the natural world and therefore, perhaps slightly unusually for most American Presbyterians maybe.

At least at that time, she was quite happy with the idea of evolution. It never bothered her christian principles at all, if you like. So there was this book and I just thought this stuff was amazing. And so from a very early age, I was probably about 11 I would think, I got very interested in human evolution.

And where we lived in east Africa was not very far from where the big fossil discoveries were made in the sixties in particular, by the Leakey family of all these different species of early human ancestors that were running around Eastern and South Africa for a very long time.

The south African fossil humans had been discovered in the fifties, but these African ones weren't really discovered till the sixties. So as I came up to being a teenager from 1960 onwards. So these the newspaper reports and people out there, cause it was not very far away.

We're often discussing would hear the adults talking about these things maybe. I was interested. I, knew something about these. So this alerted me to the conversation or alerted me to the newspaper article that something interesting was going on.

Whereas if I hadn't been interested, I guess I wouldn't even have paid attention and wouldn't have known about it, but through all my childhood teenage years in particular, constantly interested in human evolution and reading books on human evolution.

I think the first lecture I ever gave was when I was 14 on human evolution at school. In class, we had to give a lecture on something, anything that interested us, a hobby, whatever.

So I did mine on human evolution.

Ling Yah: And how did that go?

Robin Dunbar: I think it completely confused the entire class, because they had no idea what I was talking about.

Human evolution wasn't done in the school curriculum in those days. Really. I'm not even sure that evolution would have been mentioned in general because most of botany and zoology was about descriptive of the organisms, what they look like and what their insides look like, and these kind of things. The physiology and the anatomy, not evolutionary processes.

And anyway, the school I went to as a teenager was very small. We didn't do sociology at all. In fact, I didn't know biology, ever, in my entire school thinking about it because the junior school I went to in Africa up to the age of 13, we did no science of any kind. And in my senior school from 13 to 18, 19 we didn't do the biological sciences.

We only did physics and chemistry. I always thought science was very boring. I, I did the humanities things.

Ling Yah: How did you end up thinking I want to philosophy?

Robin Dunbar: Oh, because that was my passion really from, I guess my mid teenagers onwards say for about 15 and that was partly the fault of my cousin who is somewhat eccentric character I might say, but whom I lived with when I was in England while at school.

And he was much older than me. He was very interested in philosophy, uh, particularly philosophers like Bertrand Russell.

And he got me interested in philosophy. And I kind of ran with it really. I had the intellectual curiosity of philosophy intrigued me and I really enjoyed reading it. And it was something we didn't do at school as well. So here is some very exciting stuff.

This is all classic Western kind of Aristotlean, empirical philosophy. It's interesting actually. I was very well-versed . The other thing my cousin introduced me to was Buddhism. He was determined to go off and be a Buddhist monk....

Ling Yah: Definitely eccentric!

Robin Dunbar: in Southern China somewhere.

He discovered some very obscure buddhist monastery that was still in existence in Southern China, which was very austere and mostly involved heavily in martial arts type programs of buddhist training like, and he was very enthusiastic about that.

He never of course even got there, but he kind of introduced me to those ideas. So I was actually very familiar with kind of Buddhist philosophies in particular. But we can kind of do those kind of norm Western kinds of philosophy at universities in Britain at the time.

Well, now you might correct that. You might do if you were doing it in Asian studies department or something, but if you're doing philosophy in a philosophy degree, it would have been the ancient Greeks onwards.

Ling Yah: How do you go from wanting to be a philosopher to spending the early 1970s wandering around Africa following monkeys and antelope?

Robin Dunbar: Uh, That's another very long story. I wanted to go and study philosophy at university. When I was about I guess 17 and was in the process of applying for university places. So the only thing I was really interested in was philosophy, and that's what I wanted to do as a degree.

Now it just so happened that I got offered a place at Oxford university. And Oxford university didn't in those days, and still doesn't allow you to do philosophy on it's own. So You'd have to do it with something else and there were three options.

Philosophy and politics and economics, which is the famous course that produces most of our best journalists....

Ling Yah: and prime ministers...

Robin Dunbar: ...and prime ministers and philosophy and classics essentially.

So ancient, Greek and Latin literature, history philosophy and a new degree, which had only just been started a couple of years earlier, which was philosophy and psychology. And I looked at the other two and went, I don't think so. I've done latin at my senior school for the public exams, the A-level exams, Latin a level, and I said, that's enough. doing anymore.

It was too, too, too hard. And politics and economics just sounded terribly boring. So I chose psychology and philosophy is the least bad option. And I had no idea what psychology was because in those days you couldn't do psychology at school. There were no school courses, no school examinations or anything like that for psychology.

So off I went. Now, all the other places I applied to were for pure philosophy only. And so I often say I was very lucky because if I'd gone to any of the other universities, I would have realized eventually what I realized at Oxford was that philosophy is extremely hard. Only for people with very big brains.

And I wasn't very good at it. And I would therefore have ended up now as a very bad secondhand car salesman in some obscure small country town in England or somewhere else like that.

I offer apologies to secondhand car salesman. But the point is, I would have not had an academic career that's for sure. But because I had to do psychology, psychology kind of introduced me to the sciences.

It really turned me into a scientist despite the fact that I hated the sciences at school. And also in addition by chance, the first year of the psychology course was actually taught by the zoologists and not by the psychologist. By the zoologist department.

And this was principally Niko Tinbergen who got the Nobel prize for physiology, for his studies of psychology for establishing the study of animal behavior as a scientific discipline.

There's three of them reawarded the Nobel prize for that. And later on he taught me. He hadn't at that stage been awarded the Nobel prize, but the point was, we were introduced to his kind of zoology, his way of studying animal behavior in the field, as well as in the laboratory. And I thought this was magical.

And of course, having grown up in Africa, I was used to seeing wild animals everywhere. They were in our back garden. We would go off driving in the countryside and in the national parks and so on. and watch what were then these extraordinary, massive herds of wild animals, all these different kinds.

And we had all these birds in a rich variety of African birds in our back garden and things that creep and crawl and slither coming into your house.

All sorts. And we had a menagerie of animals. We had malgeese and cats and dogs, of course, and all sorts of things like that, or sort of tame animals around the house.

So I was very used to, if you like living with animals, which is what the ecologists wanted us to do. Go and sit with the animals and understand the world from their point of view.

So this was very enlightening and is becoming a very long story. But one of my friends in my first year, when I was doing this stuff had driven over land to India the summer before we all came to university and he wanted to do another trip. I would have preferred to go to India because I hadn't been there and my family spent two generations there.

So I would like to have seen it, but he wanted to go to Africa. So I said, okay, if that's what you want to do.

But we went to Ethiopia and the project we ended up doing there was studying baboons in the wild, the bush completely on our own.

Ling Yah: What's the experience like being so far away from civilizations tracking .

Robin Dunbar: You know, when you're 20 or 19, 20, I guess I was, and I did two trips of that at the end of my second year at university into my third year to west Africa.

That's how life is, you know, what's, what's unusual. This is what you do. You go out into the middle of the forest in the jungle. You wonder around, and sometimes you bump into things which perhaps wish you hadn't bumped into which may be a bit frightening. I had two very close encounters with snakes. One in Ethiopia and one in Senegal and a second study there where I was very lucky.

I was actually bitten, but I was very lucky that I have in both cases venom didn't go into my leg But even that didn't bother me. I grew up in Africa, you have these things all the time, you know if you live in the jungle, you're used to the jungle. It's not a frightening place.

So for me, this was just kind of normal life. That's how it is. Africa is. It certainly was then, I mean, the population has increased hugely in the last 70, 50, 60 years or whatever it is. But you know, in the fifties it was still wider places where there was nobody you could drive all day and not see, anybody off the main roads.

If you're off the main road you know, we would be walking in some of those places on foot in the bush, you might see one tribesmen coming past with his spear on his shoulder and he would just say hello how are you and passed on. And they were always interested, what are you doing here? Oh, we're following some animals crazy.

So yeah. I suppose because I grew up in Africa, I just liked wandering around in the bush if you like. It was part of my normal everyday childhood life. So it was, it was okay.

That experience of doing those short three month field projects really made me think I would like to do this.

This is good fun stuff to do. If this is science, I'm all for it. What's interesting is it's a very long and complicated road here with many twists and turns and bends and river crossings where I could have gone in a completely different direction and done something else.

But just life chances, I ended up taking particular choices, which way to go. And that ended up with me finding something fired my imagination, really trying to understand why animals behave the way they do.

We all started out many billions of years ago probably. It was the same LIBOR bacteria or something, but some of us are still bacteria, but some of us are now baboons and some of us and now antelope and some of us are who we are, humans.

So this is intriguing then. How has this happened, why is it happening to them? How has it coming to be?

Ling Yah: Were there any particular stand out moments from all these trips, because you said in your book again, that you notice how animals between each other had humanlike relationships. But I imagine, since you grew up in Africa, that's not a new thing as well, you would have observed as growing up.

Robin Dunbar: Probably not, actually I think. As a young child, I wouldn't even have thought about that. I would just be interested in a different species and, aren't they pretty, or, they behave in a funny way or aren't they clever jumping through the trees the way they do.

As a teenager, you know, mostly animals were the other end of a gun. They're for hunting rather than curiosity. But I think what that did was lay down a platform of familiarity. I was used to seeing them.

It only became interesting in this sense once I actually started studying monkeys in particular. because suddenly can ask anybody can study monkeys, and they will tell you the same thing. It is like watching a soap opera on TV, right?

This is human life in front of you in this kind of small way, or right. It's not completely human of course, but just do things more complicated. you know, You see all the kind of complexities going on . Kids trying to sort of cheat their brothers and sisters.

Little ones trying to get their mothers to give them some more food. And when the mother objects, you know, they make a big fuss about it and then they go and try to annoy somebody else.

Because they know if they annoy that other person and the other person turns around to get cross with them the mother will come and rescue them and give them some food. You tell me if this isn't human behaviour.

Ling Yah: Very familiar.

Robin Dunbar: reflecting back on my childhood as is, I kind of realize now how very formative the life I had in Africa was in terms of allowing me to notice and understand if you like, these kinds of very subtle kinds of behaviors, because I grew up in a very multicultural environment.

The population was very small. The population of Europeans is extremely small where I spent my childhood as a person, my teenage years.

There are only 30 other Europeans in total that's men, women, and children in the whole district. So there were like two other kids to play with. And I think any one of those was British anyway, the other was much younger than me, but he was a Seychellois from the Seychelles and a Dutch boy that I used to play with and that's it.

And then they lived a long way away. They have a special expedition to go out to their houses at, to play. So most of the time I was playing with the service children of cause it's is often the case in, in these countries you know, sort of India and Malaysia and places, when you live there were brought up by the servants and spent more time in the servant's houses parents' houses.

So you learn When you do that you learn whatever the local language is the way you're supposed to learn the language. It is sitting around the campfire, right. Or around the house or whatever you like. So I kind of grew up in a Swahili culture as well as British culture. I should say it should be European culture because even at the school I went to up to the age of 13, it was almost as many different nationalities.

As they were boys at the school, it was just the boys, any Greeks, the Poles, Americans, the Germans and the Spanish, Irish, there were Australians, you know. You name it. They were from all over the place. So you had all these different kind of European cultures, which if you grew up in say Britain, you wouldn't have experienced.

But secondarily also, I realized now as my father was born in India and he grew up in India, he didn't live in there till his 20 effectively the same as me in Africa. And therefore he spoke Hindi for the same reason from childhood. In fact, he spoke Hindi before he spoke English, right.

He wouldn't talk to his parents in English. If they asked him a question, he only replied in Hindi. But because he was very familiar with at least north Indians, so this is in the Ganges plains, very familiar with all the different kinds of Indian cultures and very at home with them he spoke fluent Hindi, so we had no trouble conversing with different groups of Indians, if you like.

So east Africa was full of these different groups. Gujerati is mostly Muslims. There were Hindus, Sikhs, Parsis, goings in large numbers.

So all these kind of households I would play with the kids. I knew the difference between all these cultural ethnic groups. I know which ones didn't like, which other ones, which ones did like, so not to make a mistake, you know, we're all these kinds of important things.

And then coastal east Africa is very Arabised. I know a lot of Arabic words. Therefore Arabic culture is very familiar to me So, in a way which I think no longer possible now.

Those days, if you wanted to have a conversation with somebody or to play with somebody or have a beer with somebody, you just have to accept whoever they were because the alternative was not to have a beer with any, which is clearly much worse.

So you know, those kind of small communities, you just become very immersed in this kind of multicultural environment in a very deep way.

But I think everywhere else, the population size too big so there's this terrible tendency for ethnic silos to develop very quickly . The English talk to the English and the Scots will talk to the Scotts and the Indians will talk to the Indians if they're the right ones and so on and so forth.

And I just don't think you get that kind of mixing in the way we experienced. So I'm very grateful to that, both for the breadth of cultural experiences that came. Because of it, I taught myself how to write in Arabic script so that I could write poetry in Swahili poetry in the script they originally used in the 18th century for that literature before they introduced the Roman alphabet in sort of around 1900.

But prior to that for two centuries, they've used Arabic. That's how I learned how to do that because I was very immersed in Swahili culture had a very rich literary tradition because of the connection with the Arabs Arabic culture, you know? But also because it kind of attuned me to the small differences between different cultures.

So you have the right cultural hat, right? So that you have the right conversation. Otherwise you end up kind of saying something which offends them, or they don't understand these kinds of things. You can't do that, I think, unless you really grow up in those cultures.

Ling Yah: It's fascinating to hear that you had such an unconventional childhood growing up.

Robin Dunbar: I actually didn't think it was. I mean, I think because the British went all over the world one way or another, they were always very small in numbers that they were often obliged to immerse themselves in the local culture.

These things depend on the size of the population you have.

It's true of any culture. If there are large numbers of you, you prefer to talk to your own people because you understand the jokes better and, you understand the things you should do, how you have a meal, all these kinds of things.

It's just makes life easier than struggling to try and behave in a way which is unfamiliar to.

It's only once you get large numbers of people of the same ethnic group, then they start to talk to each other. Africa is a big empty continent by and large and the population was relatively small. Particularly in places like Tanganyika, where I grew up where the European population was extremely smaller hardly any British in the pool because it was not a colony, it was mandated Turk.

There were more Germans and Greeks and Italians there than there were British. But along the way as well as Arabs and completely dwarfed by different Indian groups have to come over all engaged in different things.

They ran all the garages electrical staff. they did, the governs Dominated the financial areas. All the accountants practically ran the place. There wasn't even in the empire, it was extraordinary, Britain has a very small population and a very big empire.

So they were borrowing people from everywhere to run it. For example the entire Indian forestry service was run by Germans throughout the whole period until the first world war. I think actually be honest until the second world war the Indian forestry services is created by the British Indian government to try and manage the forest and so on.

Was actually run by Germans because they asked around and they were told that the Germans are the best botanists in the world. So they employed Germans. to run it.

Wasn't really a British empire. It was everybody else's in a funny sort of way. If you look below the surface it was multi-racial.

Ling Yah: What you shared certainly resonates with me. Something as simple as me going to the UK to study Malaysians tend to just hang out with Malaysians and it's so much harder to break out of it. Would you say that because you also propose this seven pillars of friendships and you've got things like same language, same location.

Would you say that these are same values? Are there certain pillars that are more important than others that make a friendship?

Robin Dunbar: So the seven pillars of friendship, I was thinking of them as like kind of a cultural barcode. Like in the supermarket barcode, but instead of having it on your forehead as little stripes of white lines you speak to them, right?

So the moment you start speaking, I know a lot about you, right? I can tell from just how you speak the language, whether you come from my village or not. Sometimes I can do a lot better than that. If you know the dialects of English very well that say English as spoken in Britain, you can place somebody's birth place to within 25 miles of where they were born just by their dialect. The moment they opened their mouth.

And this is true, all languages, I think. That's clearly cultural. You learn that. I mean, it's hard to change it, so you never quite speak another language like a native speaker when you learn it later.

If you wanna learn to speak a language as a native speaker, you have to learn it maybe in the first five years when you're learning your own home language. That always is much, much more convincing unless you're an extremely good actor. Otherwise you always speak with what is famously referred to as mid Atlantic.

This is all the British going over to America, particularly academic is going to teach in American universities. And then you try and learn the local language or the local dialect so you fit in better, right? So you're trying to speak American, but you can't quite get it. Right. So this is always referred to as mid Atlantic. We know you don't really belong here, but you're trying, I guess.

What these really are, are markers of the community you grew up in. Not so much where you're born, I think is where you were socialized, where you learnt how to be a member of the community that you belong to. And of course, all these can change to some extent through your life.

And that reflects the communities you then are part of later in life, These things do move and that, that is important in allowing other people to identify whether you belong to their community or belonging enough to their community, for them to know how to interact with you. And that's important for two reasons.

One is it tells you how much I can trust you, because if we think alike, come from the same community, then we know how that community behaves. I know when you say I will do this, do you mean I will do it one day or I will do it tomorrow? What is the local, culture on these kinds of things.

But also it means I don't have to explain my jokes to you. you're part of that joking community. You understand? We know the same kind of streets. We might not have been living in the streets at the same time, because maybe you're younger than me or older than me, but we all went to the same cafe or the same bar, you know, the same club when we were teenagers. It's those kinds of things.

And that then has the second benefit of that is that we can have a conversation which flows naturally. You know, there are no pauses while everybody's kind of thinking, oh, well, what can I say? What will this person be interested? I know what you're interested in because we come from the same community. And that community is very, very small.

As I say, it can change over your lifetime as you move from one community to another, for different periods during your life .But the record of your community ancestry is still there in the way you speak your dialect.

So the seven pillars are kind of interesting in this sense because they allow us to create and make these small scale bonded communities of just a few hundred people and we'll look after each other, I guess is the answer. But what's interesting is these seven pillars kind of overwhelm most of the other differences.

One of the characteristics of friendship we've come to understand only the last five or 10 years really is underpinned by what's called homophily, which means the love of the same, essentially. So all our friends tend to be very similar to us. That's exactly why we get, you know, silos and these kinds of things in the web-based world, social media in particular.

But the kinds of criteria we use come in two kinds, one of which is kind of pretty much fixed. So there are things like sex, are you male or female? What ethnicity?

Ethnicity is not skin color as such. It's culture, right? Say they have the same skin color cause you come from the same country, but you come to different parts In England, the big division is between the north and the south. The language is different. Dialect is completely different, even the way people think how friendly they are, is very different.

In the north they're very friendly. In the south they're very cold. And that's nevermind the different speaking English and the Scots and the Welsh.

Skin colour comes into that because it's kind of marker whether you you're likely to come from the same community as me. Age is another big effect. All our friends tend to be the same age of us, roughly speaking. Personality has a big effect. So extroverts prefer extroverts, introverts prefer introverts, but what's interesting is these markers, these fixed biological, psychological markers for friendship formation kind of die away in the face of the seven pillars, the cultural markers.

So ethnicity in particular disappears as an important marker. Once you get to know the person better. Ethnicity is functioning as a very crude first marker, if you like for belonging to the same culture. So if you get past that to actually talk to the person, then you can find out what they really liked and disliked.

Yeah. You like football as well. Aha. Okay. Now we have a friendship. So this is, I think, kind of encouraging and, interesting at the same time. These things are not kind of completely fixed.

Ling Yah: You said that extroverts attract extroverts, but then there's this common saying opposites attract.

So how do you line these two up?

Robin Dunbar: I think it's completely untrue. This is wishful thinking more than anything else because it turns out that even in romantic relationships the more similar you are, the longer the relationship.

The exception to that and possibly is the origin of this saying that that opposites attract is that it can work.

So what you're talking about with all these things, it doesn't matter whether it's a family relationship, whether it's how you get on with a member of your family whether it's a friendship and the usual sensitivity know whether it's a romantic relationship. The issue is simply how long is it gonna last, right.

And what are the forces that bring it together? And it turns out the seven pillars and the other kind of whole biological traits are very high predictive of how long a relationship, but how close the relationship will last. The more of the seven pillars, the more of these seven dimensions you can tick for somebody else the stronger that friendship will be. The more emotionally close to that friendship will be in the longer it will last.

What happens on Saturday night this is the example. The obvious example is you have an introvert and a negative. So, the extrovert wants to go out clubbing and dancing and partying, and the introvert goes, ah, can't we stay in and watch a film on the TV and have a takeout dinner. We'll send for a pizza or something and we'll stay in. And say, you have conflict already now, you know.

There's no compromise here. There's no middle road because you know, you either stay in or you go out. Whatever you do, somebody who's going to be unhappy. So it's how to minimize the amount of decisions which are complicated in that way.

They just kind of work easier the more similar you are in these kinds of ways. Now the exception to that is if you have a complete extrovert and a complete introvert who just says, oh, whatever, I don't mind if we do you want to do all right.

Ling Yah: So that's the given.

Robin Dunbar: Yeah, then of course it's going to work and it will work perfectly well. It will be very satisfactory. And if it's a marriage, it will be a marriage in heaven, I'm sure.

Ling Yah: As you were speaking, I was thinking of the word diversity, inclusivity, corporates are constantly talking about, we need to represent it. It sounds like this is sort of doomed to failure.

Robin Dunbar: No, I don't think so because okay, the world of work is a social world. Let's be clear about that, It doesn't exist in a kind of vacuum of very clever brains that sit in their rooms on their own and think up clever products or clever machines to make clever products or anything like that.

At the end of the day, these things were functional businesses or organizations doesn't matter if it's a government department ministry, whether it's a school hospital, a business, whatever, you know, involves people and to make it work, have to talk to each other. they may not be best friends, but they have to get along.

So in the end you could quite reasonably say, okay, well, if you had everybody who is matched on the seven pillars this would help the organization work more efficiently, right?

Everybody knows where they're coming from. The only downside to that is you probably wouldn't produce anything interesting because most of the clever stuff require imagination and creativity.

And very often it comes from discussion and probably they disagree to begin with.

And then they come to recognize there's a third way, which is even better and they can both agree about Many of the big discoveries have come from people from outside the subject looking in over the shoulders of the people, working on the topic and say, oh, no, I think you've missed something here.

And usually that creates a revolution in that discipline. The very famous one is the atomic theory of chemistry, which we now have, which was effectively invented by an accountant.

The YCA who invented it, it was just kind of essentially the accountant or the manager, you know, a particular government department. And he just happened to notice that in some experiments, by other people, the numbers didn't add up.

He was thinking about equations and costs and income and expenditure have to balance and all these kind of things. And he said, there's something missing here. Something called oxygen when you have a fire. Right. So they were trying to understand why things burst into flames.

And that created a completely new approach in our understanding of chemistries 250 years ago and gave us the modern theory of atomic theory. The only way that can happen is people bring different perspectives with them.

So you need diversity, that's for sure. I think that's the important lesson in life and in biology, there is no such thing as certainty.

So there are times when having a very homogenous group is highly beneficial, but there are times when it's not. So the times when it's beneficial is if you want a technical problem.

You want people who are all experts in those areas. So because they can talk to each other the point about that is they don't have to explain things to each other because they understand the background and that then becomes important.

But then if let's say your management groups are all the same, then you don't get creativity.

So it depends what it is. Are you trying to solve a problem or are you inventing new product or a new way of doing something?

As in business that always involves both invention and production. And for invention, you want diversity for production.

Ling Yah: And I imagine to optimize that productivity is governed by Dunbar's number, which is so named by yourself.

Robin Dunbar: I would have to say yes. Wouldn't you agree? Yes. Yes. So Dunbar's number I didn't invent the name.

Ling Yah: I heard it came from Facebook. How did it come about?

Robin Dunbar: That's what I heard. This is 30 years ago now. I had come up with the idea that there is a limit on the number of relationships.

Family and friendship relationships, you can manage at any one time. And that was about 150 of these. And that was also a natural size for human organization size.

If the organization remains below about 150, then everybody can know everybody else. So you asked me to do a favor and I go, yeah alright, it's not very convenient, but I'll do it.

Whereas once you're above about 150 or so your organization gets so big that I've never met you. You come to my office and you say, do you mind helping me out?

And at that point, my response is, listen, we have enough problems in our department. You know, you guys sort your problems out. I've got many better things to do. So those kinds of tensions then create silos in organizations and create many of the problems we have with the big multinational companies, I guess.

So that was about the early nineties. Sometime in the early mid two thousands and Facebook got going. People were pressing the befriend button with complete abandoned and stack large numbers of friends on their page, many of whom they have no idea cause they weren't, it caused a lot of banks. Then people were kind of asking, you know, what's going on? Who are all these people and what am I going to do about it? And actually what I think what happened was then somebody pointed out that there was this guy in Britain who had suggested that you can only have 150 friends.

And So this is why, you know, some people are being bothered by the fact that maybe they have 500,000 friends listed on their Facebook pages. And this then led to a game which shall we say international burger chains played where they invented this game, I forget exactly the details, but it was kind of like, come and collect a free burger from us if you get rid of, a hundred of your friends.

So this created a jokey kind of environment, I guess, but also cause this number to be associated with my name and then quite soon afterwards, people started to publish papers about Dunbar's number.

Ling Yah: You must have experienced a tremendous impact personally, all these emails and people coming to you. Who is Dunbar?

Robin Dunbar: It is true. I do get an awful lot of people both saying we have some kind of a club or association or something like that. And we're very concerned that, you know, maybe it's too big now and how do you suggest we organize it so that it doesn't fall apart?

Or we've noticed that now we've gone above, let's say 150 or something 200, then it starts to not functioning very well. People are not coming to our meetings. How can we do this?

Yeah. If you weren't on Facebook, you'd also have a thousand friends. You know, some of them are called acquaintances. Facebook calls them all friends. And some of them even strangers on Facebook still calls them all friends.

But in real life we know the difference. We know that we have some very close friends we're very fond of. And we have some people we kind of know them, we'd say hello to them, we may have a little conversation about something.

Some of those people are the people we work with. We see them quite often, but we wouldn't invite them home to our house. We wouldn't invite them to our big party. They wouldn't come to our wedding.

We're kind of very aware of these distinctions. But I think there's a kind of problem where particularly boys would see signing up friends as a game, right? A boy, you learn, in the teenage years that girls like boys who are very attractive to other people, right?

So clearly the best way to catch the girls is to have lots of friends so they sign up lots of friends on Facebook and the app got a thousand, 2000 friends on Facebook, but they don't understand the, actually what the girls have in mind is something very different. They mean friends, not just names Facebook.

What we do know, however, is that not very many people have more than about 500 friends on Facebook. This is a survey of 61 million Facebook pages. The average number of friends was 149.

Ling Yah: Assuming people listening have never heard of Dunbar's number or a hundred forty nine hundred fifty. How did you come on with that number? And what is that distinguishing factor between 150, as you mentioned.

Robin Dunbar: The number itself originally came up as a prediction from studying the size of groups in monkeys, snakes, primates. I was trying to solve a completely separate problem, and I was plotting the typical size of groups in different species of monkey and apes. I guess the size of their brains to test a particular hypothesis.

And there was quite a good fit. And so I had the idea of putting humans. Into the same equation, seeing what it predicted for humans. So human brains phones, the pretty is about, about 150.

You had this idea at 3:00 AM.

Well, I, yes, it was probably was about 3am when I came up with this idea.

So I was often in those days doing these kinds of complicated things late into the night. In those days, that's when I work best. These days, I can't. I'm finished by eight o'clock or something, and my brain is no longer capable of doing anything.

A lot of these ideas came very early in the morning. And the next morning I rushed to the library to look for the sizes of groups in humans. And the place I looked was the anthropological literature for tribal societies, because in reality, we haven't lived in these big knit cities for very long, you know, few thousand years the most.

So most of our evolutionary history, most of the time is spent as a species we've lived in hunter-gatherer societies, very small scales. So the question I ask is there a consistent size of grouping in these small-scale societies, which is about 150. And so I spent a lot of time reading, very obscure dusty books for reports from studies of hunter societies all over the world.

And they turned out in fact to average about 150 very close to 150. At that time, I thought this is about natural human groups, not your social network, not the number of friends you haven't seen so later, I thought well, that's the number of natural size of human groups, what's characteristic of those groups in these four scale societies is everybody knows everybody else. Everybody's related to everybody else, you know, by marriage or by descent.

In later times when people cultivated became agriculturalists or fishermen or something like that, then it became the size of the village. And indeed that turns out to be the characteristic size of villages. In those kinds of communities, everybody knows everybody else.

The relationships we have with the members of the group is maybe different, but nonetheless, my 150 friends and family and the village, and the same as your 150 friends and family and village.

So it caused us to go away and see if we could figure out what the typical size of human friendship circle. And so we took the view at the time that friends, meant friends and family, extended family in-laws as well. And of course your romantic partners. And so, Meaningful relationships to those turned out again to be consistent this size.

And what We've found now 150 really is an optimal size of social grouping in terms of information flow. That turns out to be what the physicist called a criticality, it's a unique point at which everything just works perfectly. It's smaller It just doesn't work quite as well.

And if it's bigger, it doesn't work quite as well. But if you get it, the number bang on it's Nirvana, suddenly everything works perfectly.

It's something odd about those numbers. and it turns out that, these numbers just all over the place, the longer it goes though, I'm kind of getting bored with just finding yet more examples, but that's, the other thing, people email and say, I just found a new example.

The interesting thing historically is we've reduced our family sizes from the average of five, which would be typical for most Tribal societies, which don't have a medicine, So they have high mortality rates for children and don't practice contraception, and we've reduced it down to one or two in the post-industrial world.

One consequence of that is now you have your 150 slots, which should be for family. But actually when you got 75 family, now you got some spare slots. So what happens is we fill those with people we would call friends, but the ones that are in the closest to us out of that, we kind of treat them much more so they're a part of our family. They become a family.

And you can see the evidence really for this very striking that there is a negative relationship between the number of friends and family you have in that social network of 150 people. say People who come from big extended families who have many cousins have fewer friends.

If you ask them why they didn't have so many friends, they'll say, cause it takes me all my time just to get around my cousins, to check them out and see how they're doing.

Ling Yah: Hey, everyone. Just a quick break to jump in and say, if you've been enjoying this podcast, please do head to the podcast platform that you listening to this on and give a rating and review. Every single review helps this podcast to grow and reach even more people.

What I found very interesting is that out of those friends outside the family, they also include say, God, and those include, say your dog. We often say that dogs are extended family member. Also includes the person on the tele if you watched them all the time. So how do you define those kind of,

Robin Dunbar: I think that's simply a consequence of the fact that effectively you like to think of it like this, 150 slots for close relationships in your brain. You can put anything there you like. There's no requirement that they have to be human. That's because they're relationships, rather than particular kinds of people. It can be people who are not close to them.

You may. hate your close family, but you love your distant cousins. You feel much closer to them than you do to your siblings, maybe for some peculiar reasons. So it's all quite flexible. So, you know, there's nothing to stop you putting in, into your 150 you know, your pet dog or your pet cat

The key is do you feel you have relationship with them, which is two ways. You talk to them and they talked to you. All right. That's the key because that's what defines friendship in the real world, the real friends.

This is what people do and they pray to God or to the saints, you know, from whatever it's like having a conversation.

And they may well believe that the Saint or God is talking to them. That's fine. It becomes a little more difficult. I suspect with a character on television, but maybe it can persuade yourself cause you see them every week. You know, you watch some soap opera. Some of these soap operas have been going for 30 years, and you grew up with them and maybe you talk to the characters, don't do that.

These kinds of things. And then if you can believe that they talk back to you, you know, sometimes they take your advice and they don't do it. They do something else. And you say, ah, they've listened to me for once. So it's like the real world. That's what happens in everyday life with our friends and family.

Of course. So, as long as you can persuade yourself that you're having a conversation with them and they know who you are and you know who they are, then that's what we consider to be a friendship. Or let's say more generally a relationship, meaningful relationship.

I just think it's harder to kind of convince yourself if they aren't there in front of you.

It's just easier if the person is standing there because how they speak to what they do. It gives you information about whether they really like you or not. You know, that therefore that relationship is going to be more real. You're going to know if you can trust that person because of how they behave.

Whereas with somebody who's not physically present, if even, especially if they're a figment of your imagination as Mike B with a character on the television, then you have no guarantees that you've actually understood how reliable and how honest they are as a friend. Luckily you don't have to lend them a hundred dollars or anything, but it explains maybe why we do have problems with romantic scams on the internet, right?

Because I think with all relationships, but especially so with romantic ones, what you're actually doing is falling in love with an avatar in your mind. Right. You have this belief that his, this perfect person, wonderful person that you've met and you invent all sorts of good things about them.

And then they have no bad things. Remember this everywhere. Everybody does it. And we kind of do it with friends as well. But it's somewhat less important, but especially important with, romantic partners, I think. But as you live with them, go out with them as the relationship develops.

So you learn from practical experience, which bits of your avatar are true and which are in exaggeration, right? So you kind of tweak your avatar, which is something a bit more resembling, but it's, we have this natural tendency to What we refer to by falling in love. That is what this phenomenon is.

And we do it with friends. You know, it was the first time we meet some of these. It's very exciting. What's now got this new friend, you know, they're wonderful. they're have a brain, the size of the planet, and they're so generous. They dress so beautifully and the taste is perfect and the music they love is wonderful.

And we have all these exaggerations and it it's what makes you kind of get off the fence and try and be the friend or the romantic partner, because otherwise you would sit on the fence going, ah, if I ask her out, will she say no? Or will she say yes, ah, that's quite, I don't know what to do.

Should I shouldn't I, and so you would just sit there, but if you kind of believe this person is the most wonderful person in the world, and there's a very good chance they're in love with you or would be your best friend, then you're willing to take the risk and go ring them up, you know? And eventually if you ring them up too much, they just say, stop ringing me.

And you know, this is a mistake, right. But now, and again, it happens often enough that they reciprocate because it's trying to get two people coordinated. That's the problem. and agree to spend a lot of time with. So, this is what romantic scammers on the internet trade on. they exploited this fact that you fall head over heels in love with somebody, and so long as they don't meet you, you will continue to fall in love with the avatar in your mind and think the avatar is the real person.

And if they leave it long enough and keep the relationship going on the internet long enough, you'll become so deeply sucked into this. So deeply immersed into this avatar in your mind that even when you meet the person and they turned out not to be as beautifully handsome and beautifully well-dressed and rich, all these other things that we want in our romantic partners, you'll kind of forgive them because you are just too committed to the relationship.

So they're trying to make you so completely committed that when they finally come and meet you and say, could you lend me a hundred thousand dollars? You will say yes, of course, because I love you, it's exploiting or kind of net pro psychology, I think.

But it's also very effective romantic scams on the internet costs, billions of dollars every year, and of course they ruined people's lives because they often end up selling their house to give the scammer, the money. So, it's like everything in biology in life, nothing is perfect.

Everything has a good, and a bad side. And so we need this kind of falling in love phenomenon. Otherwise we wouldn't form romantic relationships. We wouldn't form a friendships, but on the other hand, it exposes us to dangers. So we have to take caution.

Ling Yah: So the interesting thing is that people are aware of romantic scams, but still happen.

So is there a way to mitigate it because it's one thing to have the head knowledge, but you're emotionally involved in it and you just can't stop.

Robin Dunbar: I know and I think that's the problem. It's very difficult to guard against that because it's such an emotional thing. And even when you're told, you know, the police come round to your house and say, look, this person is scamming you. Do not contact them again.

And intellectually you say, of course, that's very stupid. I won't do it. But then the moment you're in contact again, maybe you don't reply, but they keep sending you messages saying, Hey, where are you? Where are you? Where are you? And so you feel kind of, oh, well maybe I'll just reply and say, well, hello and goodbye.

But you know, they always treat you very nicely. Maybe they send you a little presents or something like this. Now it's really is quite nice, this person. So you forgive them and you're back to square one. That happens all the time. But it's always vulnerable people and they're very careful who they choose.

They are looking for people who have money. for example, they were asking very early on in their exchanges: do you own a house? Do you have some savings? If you say, no, I rent my house. I'm a poor old pensioner with no money. You won't hear from them again.

They will stop, because there's no point you've got nothing. All they want is your money. But the moment you say, oh yeah, I am my house and I have another property as well. Oh danger because now they know there's something you can cash in and give them money quite quickly probably. It's a push for it.

They give you this long sob story. You know, I have this cancer or something like that. I need medical treatment. It's very expensive. I need a hundred thousand dollars to pay the fees. Otherwise I'm going to die tomorrow.

Ling Yah: It sounds like there isn't anything you can do to prevent yourself from falling in.

Robin Dunbar: It happens all the time. I was just listening today, even on the radio. Some young people in their twenties being caught by financial scams because they weren't paying attention really. They thought it was a friend and it wasn't different. Somebody hacked into a friend's account.

But with romantic scams on the internet, the big danger is your state in life. So the people they really go for are people who are older and maybe a widowed or divorced because they are looking for a new love to fill their life again.

And these days, the place to do that is on the internet, on dating sites because where do you go otherwise?

Where do you meet people who are similar to you? Who are that age, who know divorced or whatever, have you, and therefore a free cause everybody else is already married. And so, it's people in those kinds of brackets.

For example, career women, who've never got married because of their careers have dominated what they do.

Come late fifties, sixties, they start to go, hang on a minute. Life has just passed me by, I need to find a romantic partner and settle down and just have some home time if you like. And that's a very, very dangerous situation to be in because you know, the market is very small.

You have to grab what you can, because if you don't grab them, somebody else will. Because there aren't so many people in your age group that are looking for partners too. It affects both sexes, of course but usually women they targeted more.

Ling Yah: Speaking of virtual relationships, right now there is Web 3. Everyone's online.

You had the pandemic where everyone's on zoom and you have been very vocal in the fact that people need to meet physically. I need to see the whites of your eyes so that I can connect with you.

How is that possible? What are your thoughts basically in this day and age, where everyone is basically putting up a GIF of an ape and you have got, say, Mark Zuckerberg, who you know, has this avatar, which totally doesn't look like him at all.

And you definitely don't see the actual whites of his eyes.

Robin Dunbar: Yes. This is exactly this romantic scam problem. Put it in this context at the end of the day, the whole purpose of having a good friend is to have somebody whom you've been have fun with because you get on with them.

Well, right. You get into this theater or go for walks in the mountains, or, play tennis with, or, go to the films or the whatever. But also somebody who, because they work within that context is then likely to help you out.

There'll be a good friend in the sense of, if you need to borrow some money, they will help give you the money. If they need, if you need some help with your house in some way, moving house or something, they'll come and help you out. If you need advice from them, they will give you advice you can trust. That's the key thing.

And the problem is you can only do that really effectively by walking around the corner and knocking on their door, You certainly can't go to the cinema or out for a meal online.

Yeah. Give you some advice online, maybe, but it's still not the same psychologically. It still doesn't seem to be the same as if he can sit across the table in a bar or a cafe or a quiet place. And as you say, stare into the whites of their eyes and see what they really mean. Cause they're looking away all the time and they're saying, don't do this.

I wouldn't do it. But I actually went, look you in the eye and you know that they're not giving you So the great problem with online things is most of the things we use for bonding and creating friendships, which are dancing, singing, eating together telling stories, these are all difficult to do online.

There's a kind of substitute, but it really doesn't work properly. So there's something about the physical contact that seems to be important.

Ling Yah: Do you think we might come close to that? For instance, we're looking at the younger generation who have basically grown up online and then you've got all these metaverses coming out where I can say, Hey I'm knocking on your virtual door. Let's walk down this virtual street, shop in this virtual Zara and go to the cinema and watch it together.

Robin Dunbar: The answer is no. At the end of the day, what I think is very good and the reason the virtual world vision social media worked as well as they have done is they're quite good sticking plasters. That's how I would describe it. Right. So if you can't go and knock on somebody's door, because they've moved, or something and you want to keep that relationship going.

Then social media, telephone, whatever, all these things, email, they all work quite well, if you know the person, right. They work better if you know the person. Because otherwise what happens is friendships just decay quietly if you don't see the person.

If you don't contact them with very specific frequencies intervals relationships will decay naturally. And eventually they'll kind of drift down and become somebody I once knew, but like such a long time since I've seen them and I can barely remember now what they look like.

And anyway, when we meet, you know, suddenly you look very different because you are 20 years older. I didn't recognize because I have this avatar in my head of what you were originally like when you were 20 years younger.

You know, these kinds of virtual media, and I think they do work. There's no question, but I think there are just temporary devices that hold up, stop the decay happening quite so fast.

It went stop it altogether. If you don't see the person, unless they were a very, very good friend. And that probably means one, two, maybe three, but not more of your kind of best, best friends from maybe your teenage years or your college years. Those seem to survive the test of time.

The reason they survived the test time is because I think you did a lot of things with them that we all do at that age, which is extremely important part of the mechanisms of social bonding. Those sort of best friend forever relationships, or kind of grounding stone, you know, you can be separated by circumstances.

And 50 years later, you can meet up again and you can just pick the friendship up where you left it off. It hasn't changed one bit, but it is very, very, very small number of people you can do that with. because most of the people I guarantee that.

You go to a college or a high school reunion when you're 40 or 50, you know, we haven't seen each other for all this time. It's kind of interesting and you have quite a nice time, but at the end of it, you come away thinking really, were they my friends?

They are awful, most of them. And it's because your seven pillars are originally almost identical, but over the 30 or 40 years, you've drifted apart.

You've changed your religion maybe, or your political views or what have you gone off your careers have been very different. You've got nothing in common anymore. So know this is one reason in a sense why you shouldn't try and keep those relationships going because It's okay for the less close ones.

But you know, for your close friends, the relationships we pull the shoulders to cry on friends, which is about five people. These people that will, drop everything when your world falls apart and come to pick you up and help you out.

These people require a lot of attention and it has to be regular. So if they move away, you've got to make a big effort to try and see them more often because there seems to be nothing like being face-to-face with them to keep that relationship burning. And I think a lot of that is because it involves a lot of physical touch stroking and patting and hugs and all these kinds of things we do with our closer friends and family.

Whenever we're talking to them, we're constantly touching them, hugging them around the shoulder. And it's just going on quietly in the background.

All this is triggering the same mechanism in the brain that creates this bonding that is also triggered by things like laughter and dancing and singing, eating together.

So at the end of the day, there's something about the physical contact that goes on in conversation, or when we engage socially with people that is very important for creating highly bonded relationships.

So if you don't do that, if you only rely on the media, I think you end up with weak relationships. You will never have relationships which are so emotionally powerful that when your world falls apart, those two or three people come rushing to your aid. These kinds of disasters only happened to us once in a while.

This is the illusion that's created now. I can do all my social relationships online. I don't need to see people. My answer is simply just wait till your world falls apart. You'll find out who your friends really are.

Ling Yah: I love that you've doubled down the fact that we must meet in person, and I wanted to put a problem to you, which is happening right now. There's this thing called NFTs. And so people are buying all these JPEGs and that allows you to join a particular community. And so the founders will release 10,000 of them.

One person might hold two. So you have talking about 5,000 people in a community on Discord. And more often than not, these people join many, many, many projects. So you're in probably five to 10 to 20 of these communities, 10,000 people's strong. Is it possible to be a community?

How would you do it if you were asked, please help me build a community for my people in this project.

Robin Dunbar: What you end up with is very weak relationship. That's all you can possibly have. or at least You can have strong relationships, but they will have no more stronger relationships than the usual ones, 50 or 150, or, you know, those kind of layers that we have.

However, what we can do and what has been important in the course of human evolution is the fact that we can create clubs. So this has been our solution to how to increase the size of our villages, to make towns, to make cities, to make nations modern states and so on which are much, much bigger than 150.

It's what we call one-dimensional clubs.

They're taking one of the seven pillars and just using that to create a relationship, but by definition, it's a weak relationship, right? and That allows you to have very large numbers of people in the club, because what you are really creating is the relationship to the club, not to the members of the club, as individuals.

So You see it in things like rotary, those kind of semi business, semi-social organizations that are worldwide, right? So if you're a member of the rotary club in your home city, if you go anywhere in the world, you can check out is there a rotary club the town I'm in now? and then you can go along and join their meeting and meet the people. And you're very welcome because you are a member of our club, right? So this works extremely well, but it, only works at a certain level of friendship.

These are weak relationships by and large, unless they're religious. Religion seems to create this particular, intensity relationship, which allows you to see all members of your particular religion as being kind of brothers and sisters. Part of the reason that works is often those religions use this kind of family terminology.

You know, we are the family of Christ. We are the brothers and sisters of the world church. In the Western Christian tradition, the term father is used for a priest, or mother superior for the head nun. All these family kinship terms are being used to create this sense that it really is a family. But that's the only one.

There's something odd about religion that allows us to create these very, very strong, committed relationships over very large numbers of people who we don't necessarily know in a way which really doesn't work in with secular examples.

The smaller, the religion, the better. If you come along and say, I belong to some very obscure, small religion , I'll welcome you into my house. It's a long lost friend. I don't know who you are, but we both belong to this tiny little religion that nobody's ever heard of, then it gives us a sense of belonging to a very strong community.

But in general, this outside religion never really works. It doesn't have the same sense of obligation and commitment for some reason. . But the other interesting thing about clubs is that they work better with the boys than with the girls.

Boys like clubs because their relationships are much more casual. I think it's a very dyadic and focused and specific to the individual.

So if you're my friend as a girl, then it's because of who you are, right.

Boys kind of don't do that. Boys friendships are much more casual. It's more a case of belonging to the clubs. If you belong to my club you are my friend. And. Your criteria for being my friend is you belong to the same club as me. Whatever that club can be defined, as long as it's an activity.

And this is the other thing, girls relationships are really built on talking together, kind of like exchanging secrets, but, actually physically engaged in conversation. If they want to keep the friendship going, they got to talk more to each other.

Well, for boys friendships, it has no effect whether they talk more, a bit, none at all, it's all the same.

The only thing that's important for them in their case is doing stuff. And that's that club sense. It's memberships of the clubs that entitles you to be my friend, but it doesn't matter who you are.

Girls would be very upset. They will go on to Facebook and texting and stuff.

Boys will just go, okay, if you don't want to come drinking with me or playing football or whatever we used did it, I'll just get somebody else to come and join. that then becomes my new friend.

My suspicion is that most of the people that find that kind of metaverse environment congenial probably the boys and less the girls. Not to say that some girls wouldn't enjoy it and find it very congenial. But in terms of.

the numbers overall. my guess is it will be much more popular with the boys, much less popular with the girls because girls will go. I really want to just sit down with you and have a chat.

Ling Yah: That's certainly proven true. Most of the massively popular and successful projects are run by men, and then you have the females going, but why? There's no purpose behind what they are doing. And we are giving all the purpose and the meaning behind this project we're doing, yes.

There was another question I was thinking as you were speaking. So thinking of this boys-led projects very popular, and people flex, and they're very proud of the fact we are part of this club.

It's only 5,000 of us. You can never join, even though the whole world wants to.

But underpinning everything right now in the metaverse is money. And the reason is because one of this membership club essentially is worth half a million dollars. And if I want a quick flip, I can just sell it to someone and someone else will come in.

So, would you say that the relationship is already virtual, it's weak, and then you add money in, so it's even weaker.

Robin Dunbar: Yep. It's the fact that what becomes important in these kinds of clubs clearly is a kind of exclusivity to it. It's all about kind of how narrowly you can draw the circle for being included in the club. And therefore, one of the ways we do that is we put a monetary value on it.

You want to join my golf club? You know, it is very expensive and therefore very exclusive. If you can't afford our fees, well, there's a very cheap one down the other side of the city.

Maybe you can join, so we kind of signal, you know, and that's, again, back to the homophily kind of thing, you know, I'm signaling that I'm in your community because I'm wealthy enough to pay the fee to join your club.

Right? And that's all that you are seeing with these kinds of metaverse things.

Ling Yah: Would you say that FOMO fear of missing out is a strong bonding mechanism? And I say that because in the metaverse world, the NFT world FOMO is a huge part.

The other day there was this project that was launched: moon birds.

And if you had one of those in four days, you have 10 X your profit. You could buy a house, you could buy a Lambo. People are made millionaires within hours or days.

And then if the world is looking at it going, have FOMO, I wish I was a part of this project. And so it's just clouded everything.

Robin Dunbar: But also those sorts of things, they're Ponzi systems basically, right? They rely on everybody putting in a small amount of money and then one person getting it all. So they're just Ponzi schemes.

And in that sense, they're like lotteries. Only there is some kind of membership activity that goes on, that makes you feel part of the community so you don't run away.

There's a trade-off here.

Ling Yah: Well, you could just sit together and watch a stand-up comedy show.

Robin Dunbar: That's right. There's some activity that's going on that gives you some small payoff, which is enough to make you stay in the club. You have to have some intermediate payoff, you know, like having a bit of fun or perhaps having an online chat or whatever.

So yeah, personally, I wouldn't do it. These online environments, therapy they're interesting but it's not something I would be tempted to invest my money in. I'd rather invested in real people in the pub,

Ling Yah: If you were asked to decide on, and this is an assumption to invest in certain relationships virtually.

And I got this question from a previous guest who is actually building this web 3 community and she wanted to know what you thought of, how do I decide on which relationships invest in since there is so much FOMO going on. How will you think about it?

Robin Dunbar: Relationships online. It's tricky because it's hard to know in the face-to-face world, you use these ground-truthing features of meeting the person and seeing how they really do behave and getting a feel for their reliability and their honesty and truthfulness and so on.

You're using facial cues and just the way they say things, the tone of voice and not what they say.